|

Abstract

Extraskeletal bone tumors are rare and high grade tumors

including osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma of

the soft tissues and its variants. A retrospective study of 25

cases of these tumors was made in our institution in the 1983 -

2000 period. The study of 25 cases revealed that these tumors

affect adults (median age 51.2, range 17-73 years). The most

common tumor locations were the thigh (12 cases, 48%) and the

arm-elbow (6 cases, 24%). As a classification for diagnostic

type of tumors: 14 were chondrosarcomas (56%), 8 were

osteosarcomas (32%) and 3 were Ewing sarcomas (12%). The median

follow-up was 47.07 months with a range from 24 months to 156

months. All the cases were treated with preop. chemotherapy and

postoperative radiotherapy (with the exception of the myxoid

chondrosarcoma). Globally, the preoperative duration of symptoms

ranged from 2 weeks to 6 years (median 6 months). Local

recurrences after wide and compartimental margin surgery

developed in 7 cases (12%), three cases of chondrosarcoma and

four cases of extraskeletal osteosarcoma; and distant metastases

developed in seven cases (6 osteosarcomas and 1 Ewing’s

sarcoma). The two year overall survival rates were:

extraeskeletal chondrosarcoma 50%, osteosarcoma 36.5% and Ewing

sarcoma 66.6%. The two year disease-free survival was: 42.8%

chondrosarcoma, 25% osteosarcoma and 33.3% Ewing sarcoma. The

interest of this series is the fact that tumors are high grade

and cure may be achieved by wide or compartimental local

excision of the tumor at an early stage of the disease (combined

with radiation and chemotherapy).

J.Orthopaedics 2006;3(4)e7

Introduction:

Extraskeletal primary bone sarcomas are rare

and high-grade tumors that include osteosarcoma (OS),

chondrosarcoma (CHO) and Ewing sarcoma (EW) of the soft tissues

and its variants.

Osteosarcoma of the soft tissues is a

malignant mesenchymal tumor whose cells produce osteoid

substance. Unlike skeletal osteosarcoma it is observed during

adult and advanced age and particularly in women. The sites most

involved are the thighs, the muscles of the pelvic girdle and

the shoulder. Radiographically, there may be areas or nodules of

faced radiopacity, due to tumoral osteogenesis. Microscopically,

skeletal osteosarcoma (OS) is prevalently osteoblastic, but

chondroblastic and/or fibroblastic areas may be present.

Differential diagnosis must include osteproductive benign

lesions (i.e. myossitis ossificans) and malignant lesions (i.e.

sarcomas with osteogenesis of a metaplastic nature). The

prognosis is very severe, as pulmonary metastasis frequently

occurs. The treatment is the same as for skeletal OS:

preoperative chemotherapy, wide or radical surgery, and

maintenance chemotherapy.

Chondrosarcoma of the soft tissues is very

rare. Instead, almost all the cases of CHO are constituted by

myxoid forms and by mesenchymal chondrosarcoma.

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (named

chordoid sarcoma) is a rare tumor that affects men more than

women and it is almost exclusively observed during adult and

advanced age. It is specially observed deeper in the lower limb.

The radiographic picture is completely unspecific, locking

images of calcification or ossification. Histologically, it has

a lobular structure, more or less cellular; nonetheless this

differentiation hardly ever achieves the stage of

well-differentiated hyaline cartilage. Differential diagnosis

must include myxoid liposarcoma, myxoma and chordoma. The

prognosis is the same as that for skeletal chondrosarcoma, but

it has a considerable tendency to recur locally and it is

capable of metastasizing. The most suitable type of treatment

appears to be wide surgical excision.

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is rare in the

soft tissues, even more rare than in the skeleton. There is no

predilection for sex, and unlike myxoid chondrosarcoma it is

observed during young and adult age (15-40 years) and deeper in

the lower limb and neck. Clinically, again unlike myxoid

chondrosarcoma, it has a rather rapid growth. Radiographic

appearance is often sprayed by calcifications, with angiography

the tumor is injected intensely, in virtue of its rather rich

and dilated capillary circulation. Histologically, the pattern

is intense vascularization and dilated sinusoidal with

balloon-oval cells by the presence of foci of cartilaginous

differentiation. Differential diagnosis above all involves

hemangioperycitoma. Prognosis is very severe (high malignancy).

Its growth is rapid and its tendency to metastasize is also

high. The treatment includes surgery, chemotherapy and

radiation.

Synovial chondrosarcoma are exceptional cases

in which a synovial chondromatosis causes a chondrosarcoma, or

in which a chondrosarcoma originates in the joint. It is a soft

and compact cartilaginous tissue filling the joint cavity,

eroding the capsule, invading the soft tissues, digging into and

infiltrating the joint bones. It is difficult to establish

whether it was truly a chondrosarcoma or an aggressive and

tumor-like synovial chondromatosis.

Ewing sarcoma of the soft tissues remains a

rare tumor, it shows predilection for the male sex, and for

those aged between 15 and 45 years. Histologically, the aspect

is the same as that of Ewing sarcoma of the bone: uniform fields

of small and round cells. Differential diagnosis must include

neuroblastoma,embryonal or alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, and for

patients aged over 30-50 years malignant lymphoma and metastasis

of small cell carcinoma. Prognosis and treatment seem to be very

similar to what is indicated for Ewing sarcoma of the skeleton.

Method and materials

Retrospective studies of 25 cases of this

heterogenic group of tumors were made in our Hospital in the

1983 - 2000 period (Table I). The study of 25 cases revealed

that these tumors affect adults (median age 51.2, range 17-73

years). The most common tumor locations were the thigh (12

cases, 48%) and the arm-elbow (6 cases, 24%). Three tumors were

superficial (hand and foot locations, 12%), 3 pelvic locations

(12%) and 1 perone location (4%).

As a classification for diagnostic type of

tumors: 14 were chondrosarcomas(56%), 8 were osteosarcomas (32%)

and 3 were Ewing sarcomas (12%) (Table III) and staging with the

AJCC classification (Table II and III).

Fourteen extraskeletal chondrosarcomas are

distributed in 6 myxoid chondrosarcomas: 5 male and 1 female

patients, median age 58.3 years (ratio 47-70 years) with a

median follow-up of 49.5 months (ratio 24-95 months), 5 thigh

and 1 arm locations; 5 mesenchymal chondrosarcomas: 4

females and 1 male patient, median age 33.6 years (ratio 17-56

years) with a median follow-up of 30.2 months (ratio 26-36

months), 3 thighs, 1 arm and 1 foot locations and 3 synovial

chondrosarcomas: 2 male and 1 female patients, median age 47.6

years (ratio 43-55 years) with a median follow-up of 30.6 months

(ratio 28-36 months), 2 knee-thigh and 1 hip-thigh

locations.

The 6 cases of

myxoid chondrosarcoma were treated initially with wide and

compartimental surgery (three wide surgeries and three

compartimental surgeries without adjuvant and coadjuvant

treatment). The 5 cases of mesenchymal chondrosarcoma were

treated initially with wide and compartimental surgery (four

compartimental surgeries and one wide surgery) accompanied with

coadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation. The 3 cases of synovial

chondrosarcoma were treated initially with wide surgery

associated in this kind of tumor, in one case with coadjuvant

chemotherapy and in another case with postoperative radiation;

in one case supracondylar amputation is performed and in another

case hemipelvectomy is preformed for tumor local persistence.

|

STAGE |

GRADE |

TUMOR (T) |

LIMPHATIC

NODES(N) |

METASTASIS

(M) |

|

IA |

Low |

T1a-1b |

N0 |

M0 |

|

IB |

Low |

T2a-2b |

N0 |

M0 |

|

IIA |

High |

T1a-1b |

N0 |

M0 |

|

IIB |

High |

T2a |

N0 |

M0 |

|

III

|

High |

T2b |

N0 |

M0 |

|

IV |

Low and High |

T1-2

T1-2 |

N1

N0-1 |

M0

M1 |

T1a

Superficial

T1b Deep

T2 > 5 cm

T2a Superficial

T2b Deep

N1 Regional limph nodes

G 1-2 Low grade

G 3-4 High grade.

Table II.

Clasificación UICC/AJCC 2002 (VI edition).

Eight

extraskeletal osteosarcomas were revised: 6 male and 2 female

patients, median age 58 years (ratio 28-73 years) with a median

follow-up of 73.12 months (ratio 24-156 months), 3 arm-elbow, 2

pelvic, 1 arm-shoulder, 1 thigh and 1 perone locations. All of

the cases of osteosarcomas were treated initially with

preoperative or neoadjuvant chemotherapy after surgery (1 case

of initial leg supracondylar amputation, 4 cases of initial wide

surgery and 1 initial compartimental surgery were performed) and

postoperative or coadjuvant chemotherapy and postoperative

radiotherapy (except the case of initially amputation

performed). The two cases of pelvic locations were treated with

chemotherapy and radiation only (surgery is not possible in

these particular cases).

Three

extraskeletal Ewing sarcomas were studied: 3 female patients,

median age 51.6 years (ratio 46-62 years) with a median

follow-up of 29 months (ratio 24-33 months), 2 foot and 1 pelvic

locations. All the cases were treated initially with neoadjuvant

chemotherapy after surgery (2 cases of initial infracondylar

amputations in foot locations and abstention of surgery in

pelvic location) and coadjuvant chemotherapy and local

radiation.

Globally, the

preoperative duration of symptoms ranged from 2 weeks to 6 years

(median 6 months). The median follow-up was 47.07 months with a

range from 24 months to 156 months.

One case of

osteosarcoma presented a history of previous radiation and 2

cases of osteosarcoma presented a history of prior trauma.

|

Name

Diagnosis |

|

AJCC

|

|

AGS |

Myx-CHO |

II B |

|

JSS

|

Mes-CHO |

III |

|

JSA |

Myx-CHO |

II C |

|

ERM |

Mes-CHO |

III |

|

AML |

Myx-CHO |

III |

|

MTT |

Mes-CHO |

III |

|

PFP |

Myx-CHO |

II C |

|

JGB |

Myx-CHO |

II B |

|

ABN |

Mes-CHO |

III |

|

LSV |

Mes-CHO |

III |

|

AMO |

Myx-CHO |

II B |

|

MRP

|

Synovial-CHO |

III |

|

ROS |

Synovial-CHO |

III |

|

JMC |

OS |

III |

|

JVB |

OS |

II C |

|

FSM |

OS |

III |

|

JNM |

OS |

III |

|

EMG |

OS |

IV B |

|

AMF |

OS |

III |

|

EMG |

OS |

IV B |

|

AMF |

OS |

II C |

|

JOA |

EW |

III |

|

PCL |

EW |

IV A |

|

ASS |

EW |

III |

|

MAC |

EW |

III |

Table III. Diagnostic

type of tumors and AJCC classification.

Results

Treatment complications

In the 25 cases presented, the following treatment complications

were observed: 2 superficial infections, 2 toxicity

chemotherapy, 2 ulcerated tumors with recurrence and 1

thromboembolism.

Local recurrence

Local recurrences after wide and compartimental margin

surgery developed in 7 cases (12%). Three cases of

chondrosarcoma and four cases of extraskeletal osteosarcoma.

In the cases of myxoid, mesenchymal and

synovial chondrosarcoma, eleven cases were alive with no

evidence of recurrence (78.5%).Three cases of recurrences: one

synovial chondrosarcoma of the knee one year after wide

resection, the recurrence was treated with compartimental

surgery and it had a new recurrence two years later the first

wide surgery and its was treated with a above-the-knee

amputation associated with postoperative chemotherapy. This

patient was alive with one or more recurrences and two cases of

mesenchymal chondrosarcomas treated initially with wide surgery

and ampliation of surgery at compartimental where the

recurrence was present at two and one year (one arm location and

one thigh location).

In the cases of extraskeletal osteosarcomas,

four cases were alive with no evidence of recurrence (50%), and

another four cases of recidivated extraskeletal osteosarcomas

were treated; two cases of extraskeletal osteosarcoma in the

arm-elbow developed a recurrence one year and two years later

respectively after wide resection and they were treated with an

above-the-elbow amputation and compartimental surgery

respectively associated with postoperative chemotherapy

(alive with lung metastasis). Another case presented recurrence

in arm-shoulder location two years after wide resection, and it

was treated with compartimental surgery (alive without

metastasis). One case of recurrence of extraskeletal

osteosarcoma of the thigh, one case developed a recurrence 18

months after wide resection and it was treated with a

suprecondylar amputation associated with postoperative

chemotherapy (alive without metastasis).In the cases of

extraskeletal Ewing sarcomas, none were recidivated.

Metastasic disease-Exitus

None of the cases of extraskeletal

chondrosarcomas and its variants were metastasized.

In cases of extraskeletal osteosarcoma, five cases (62.5%)

presented lung metastasis (two cases at diagnosis time) and

three cases (37.5%) died after 134 months (peroneal location),

80 months and 29 months (pelvic location), respectively. The two

cases with metastasic lung disease were arm-elbow locations

treated with wide surgery initially and subsequent amputation

above-the-elbow in one particular case after recurrence. The

other case was treated with wide resection initially. These

cases were alive with metastasic disease (25%) and achieved

local control after 156 months and 89 months respectively.

In extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma cases, one case (33%) of foot

location developed regional lymph nodes metastasis and it is

alive after 14 months at diagnosis. One pelvic case died after

33 months and another foot location case was alive without

metastasis disease after 14 months.

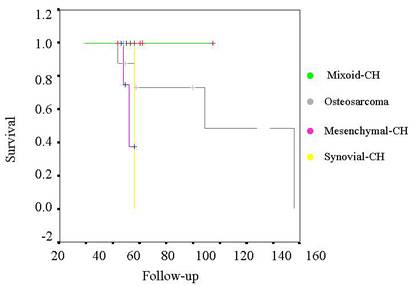

Survival rates for type of tumors

The two year overall survival rates

were: extraeskeletal chondrosarcoma 50%, osteosarcoma 36.5% and

Ewing sarcoma 66.6%. The two year disease-free survival were:

42.8% chondrosarcoma, 25% osteosarcoma and 33.3% Ewing sarcoma.

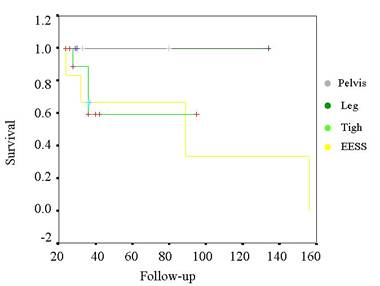

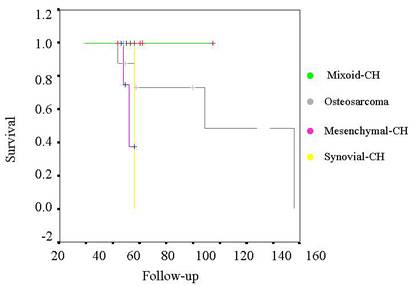

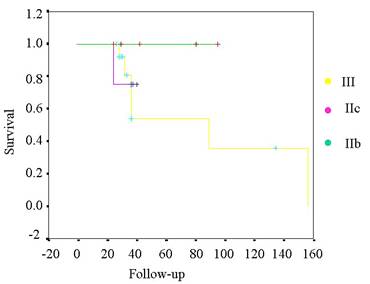

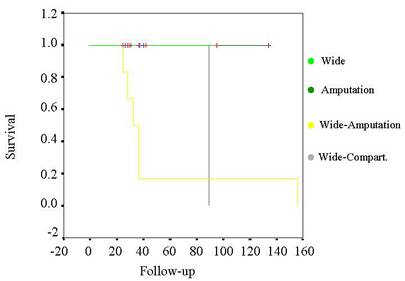

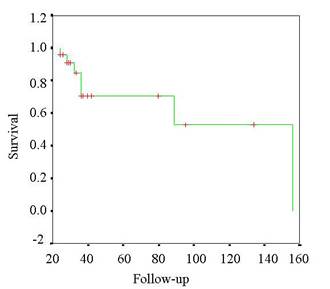

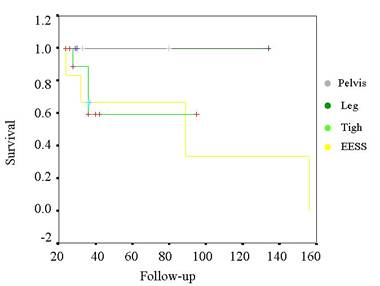

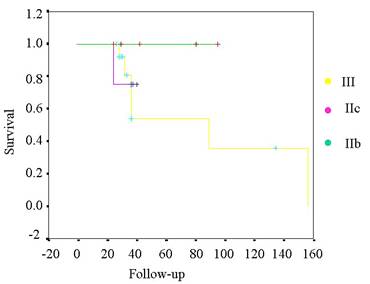

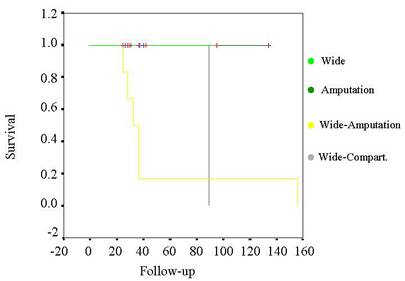

Statistical analysis

This retrospective study is based in a short series of patients

and a rare and heterogenic group of tumors. The statistical

analysis included the study of several variables: tumor

location(Table IV), type of tumor (Table V), staging system

(Table VI) and surgical treatment (Table VII) with one

curve of global overall survivor (Table VIII). This study is

presented following a Kaplan-Meier system of survivorship

curves.

Table IV.

Kaplan-Meier curve for survival of the tumors related by

surgery.

The statistical significance only was

demonstrated in the case of surgical treatment. None of the rest

of variables included in this study (diagnostic tumor, staging

system, and tumor location) are significative statistically.

Tabla V. Kaplan-Meier curve for survival

of the tumors related by histology.

Tabla VI. Kaplan-Meier curve for survival

of the tumors related by staging.

Table

VII. Kaplan-Meier

curve for survival of the tumors related by surgery.

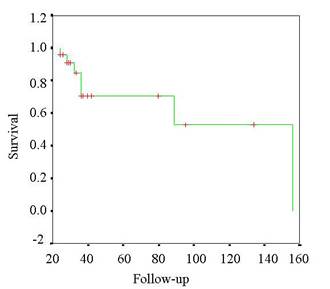

Table VIII.

Kaplan-Meier global overall survivor.

Discussion :

This group of tumors rarely occur and they are

included in the XII group of the W.H.O. classification

(WHO book)

(extraskekeletal bone tumors) in

the cases of osteosarcomas and chondrosarcomas and the group of

lesions of uncertain origin in the case of Ewing sarcoma-PNET

group.

As for osteosarcoma patients, there is a poor type of tumor

prognosis due to the aggressive biological behavior of this kind

of tumors (high tendency to local recurrence and general

dissemination). The staging of these tumors is grade II-C or

high (IV) in the American Joint Committee System Staging

(variation 1997)(

Sugarbaker book,5) : >5 cm tumors, superficial or

deep, with or without lymph and lung metastases. In

previous studies of extraskeletal osteosarcoma

(1,2) the

thigh was the most common tumor location; in our series, the

most common location is the arm-elbow and pelvic tumors (worse

prognosis for a location that prevents surgical treatment). The

extraskeletal osteosarcoma was described in more locations: hand(6),urinary

bladder, prostate, kidney, breast, lung, tiroid,

retroperitoneum

(3), frontal region(4) and

cardiac intramuscular(5) presentations.

Etiology of the cases is controversial, several theories were

performed: association with Li-Fraumeni Syndrome(7) and

myositis ossificans(8) ,

prior trauma(9) ,

radiation-induced

(10) , thorotrast-induced

(11)

and heterotopic ossification after an electrical burn

(12).

Microscopically tumors contain varying amounts of

neoplasic osteoid of bone (Figure 1), sometimes together with

islands of malignant-appearing cartilage

(13).

Figure 1. Histological pattern of extraskeletal

osteosarcoma.

Hematoxyline-

eosine

x 400.

In radiological studies extraskeletal osteosarcoma presented

nodules of faced

radiopacity ,(tumoral osteogenesis)

(14),

central ossification and inverse “zone”

phenomenon (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma of

the arm. Radiological appearence.

Bone scan

reveals uptaking in the lesion

(15) CT

scan revealed mineralized soft tissues, and MRI presentation

shows hipointense images in T1-weigthed spin echo and

hiperintense in T2-weigthed spin echo and STIR sequences.

Telangiectatic variant are least common histological variety in

this group (16).

As for the diagnosis of these, it was made by needle biopsy

(tru-cut technique in all the cases), but with appropriate

clinicoradiologic correlation extraskeletal osteosarcoma may not

be recognized easily by FNAB

(17),

unlike skeletal osteosarcoma. Like the osteosarcoma of bone,

extraskeletal osteosarcoma showed a striking variation in

histological appearance and focally resembled malignant fibrous

histiocytoma (1),

fibrosarcoma, soft tissue aneurismal bone cyst

(16 ) and

malignant schwannoma. The prevailing sites of metastases were

the lung, the regional lymph nodes and bone (none in our series

of patients). The treatment included in all the cases

neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgery (wide, compartimental or

radical) and coadjuvant chemotherapy with local postoperative

radiation. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma is a high grade

malignant tumor associated with a 5-year survival rate of 37% of

the cases. Local recurrences and distant metastasis are common

and usually occur by 3 years after excision in Mayo Clinic

series

(18). In

comparison, in our series the 2-year survival rate is 36.5 % and

the 2-year free of disease survival rate is 25%. Additional

larger series will be required before drawing definite

conclusions.

Chondrosarcoma

of the soft tissues is a rare tumor. The near totality of CHO is

instead constituted by myxoid forms, mesenchymal chondrosarcoma

and by synovial sarcoma.

Extraskeletal

myxoid chondrosarcoma is an uncommon neoplasm, according for

less than 2% of all soft tissue sarcomas. It affects adult males

with an age in the fifth decade at the time of diagnosis. The

tumor usually arises in the deep soft tissues, especially in the

lower extremities (Figure 3)(19).

Figure 3. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Thigh

location. MRI T1-weighted image.Figure 4. Histological

pattern of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma.

Hematosyline

-eosine x 200.

It is a rare low-grade soft tissue sarcoma (staging of these

tumor varies in II-B, II-C or III in the AJCC system), with

locally aggressive and metastasizing potential

(20) . It is specially observed deeper in the

lower limbs. In myxoid CHO, the cells that resemble epithelial,

can very closely mimic some malignant breast tumors in thoracic

locations (21).

A diagnosis of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma was rendered

based on histological findings

(22). Differential diagnosis included other myxoid

neoplasm such as bony myxoid chondrosarcoma, myxoid liposarcoma,

chordoma and parachordoma

(22).

Differential diagnosis

with extaskeletal chondroma: asymptomatic and harmless

clinical course, the lack of connection between the tumor and

the underlying bone, the slow tumor development, the absence of

a sex predominance and the characteristic tumor histological

picture .Typically well-circumscribed, extraskeletal myxoid

chondrosarcomas are commonly encapsulated by a rim of fibrous

tissue. The abundant myxoid matrix gives the cut surface a

gelatinous appearance. The degree of cellularity is variable;

less well-differentiated, highly cellular tumors generally have

less extracellular matrix and behave more aggressively (Figure

4) (22)

Pulmonary metastases are not unusual in this tumor, only two

patients have been reported with multiple bone metastases

(23)

In our series no adjuvant therapy is necessary, none of the

cases were disseminated. Resistance to standard soft tissue

sarcoma chemotherapy has been demonstrated

(24) .

Myxoid CHO are a better prognosis respect to synovial CHO and

mesenchymal CHO

(25).

Figure 5. MRI of

mesenchimal chondrosarcoma

of the thigh.

Figure 6.

Synovial chondromatosis of the hip.

MRI T1-weighted image. Mesenchymal

chondrosarcoma is rare in the soft tissues (making up less than

2% of all chondrosarcomas)

(26), even

more rare than in the skeleton, There is no predilection for

sex, and unlike myxoid chondrosarcoma it is observed during

young and adult age (15-40 years) and deeper in the lower limb

(Figure 5) and neck.

The

extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma was described in more

rare locations: jaw

(28) ,

intraspinal (29),

cauda equina (30),

pleura (31),

labium majus (32),

orbit (33),

heart (34),

intracranial (35),

femoral vein (36) and

vagus nerve (37).

Clinically, again unlike myxoid chondrosarcoma, it has a rather

rapid growth. Radiographic appearance is often sprayed by

calcifications, with angiography the tumor is injected

intensely, in virtue of is rather rich and dilated capillary

circulation. Histologically pattern is intense vascularization

and dilated sinusoidal with balloon-oval cells by the presence

of foci of cartilaginous differentiation

(38),

typically characterized by tumor compartmentation

(undifferentiated tumor cells in the small-cell areas were

negative for vimentin and cytoprotein S-100, whereas other tumor

cells expressed collagen type II-A and vimentin indicating a

chondroprogenitor cellular phenotype in these small areas)(39) ,

citogenetic studies of mesenchymal chondrosarcoma are few and to

date, no specific or recurrent aberrations have been found

(40,41, 42,43)

. Differential diagnosis above all involves

hemangioperycitoma. Prognosis is very severe (high malignancy)

(44). Its

growth is rapid and its tendency to metastasize is also high

(lung, bone and skin metastases

(44) ). The treatment includes surgery, chemotherapy and

radiation.

Synovial chondrosarcoma are exceptional cases in which a

synovial chondromatosis causes a chondrosarcoma

(45, 46), or in which a chondrosarcoma originates in the

joint. It is a soft and compact cartilaginous tissue filling the

joint cavity, eroding the capsule, invading the soft tissues,

digging into and infiltrating the joint bones (Figure 6).

Malignant transformation to chondrosarcoma shows no specific MR

features to distinguish these cases with malignant change of

primary synovial chondromatosis alone

(45).

Synovial chondrosarcoma is considered very rare and it is not

always clear whether the sarcoma develops by malignant

transformation of synovial chondromatosis or whether it arises

de novo. Differentiation of the two conditions based on clinical

and radiographic features is not possible and it can be

difficult (46)

based on histological criteria. The indispensable

criteria to diagnose malignant transformation are: 1)

histological diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis established

before diagnosis of chondrosarcoma, 2) histological diagnosis of

chondrosarcoma on the same anatomic site as the synovial

chondromatosis, 3) diagnosis of chondrosarcoma and synovial

chondromatosis on the same resection specimen(47).

The mo st important histological features were loss of the

“clustering” growth pattern typical of synovial chondromatosis,

myxoid change in the matrix, areas of necrosis, and splinting at

the periphery of chondroid lobules (Figure 7)

(48) . It

is difficult to establish whether it was truly a chondrosarcoma

or an aggressive and tumor like synovial chondromatosis. This

condition was described in the hip joint

(49), knee

joint (50)

, radiocarpal joint

(51), ankle

joint (52) and

metacarpophalangeal joint

(53).

Extraskeletal

Ewing sarcoma (EES) is a rare soft tissue tumor that is

morphologically indistinguishable from the more common Ewing

sarcoma of bone (Figure 8) .

Figure 7.

Histological appearence of synovial

chondrosarcoma.

Hematoxyline-eosine x400.Figure

8. Histological

pattern of extraskeletal

Ewing sarcoma. Hematoxyline-eosine x400.

It must be

distinguished from other small, blue round cell tumors (SBRCTs).

The most frequent sites of occurrence are the chest wall, lower

extremities, and paravertebral region. Less frequently, the

tumor occurs in the pelvis and hip region, the retroperitoneum,

and the upper extremities. It is usually found in young adults

(younger than 30 years) and has a slight predominance in male

patients (54).

Ewing sarcoma is the second most common primary osseous

malignancy in childhood and adolescence, and most of the

success in survival with multimodality treatment has been in

that age group. Survival rates in patients with childhood

nonmetastatic ES/PNET have improved from 10% in 1967(55) to

50% in 2000(57,58) The

improvement in survival is primarily associated with the

combination of surgery and chemotherapy. Little has been

pubfished about the outcome of adults with extraosseous (soft

tissue) ES/PNET.

Four studies to

date, regarding both skeletal and extraskeletal adult

ES/PNET(Figure 9), have been published evaluating survival and

predictors of survival. Two studies(59,60) have

demonstrated age as a poor predictor of outcome, and 2 studies(61,62) have

not seen age as an adverse risk factor. Our extraskeletal Ewing

series shows a higher median age (51.6 years) and the courious

location (2 foot cases and 1 pelvic case).

Figure 9.

Histological appearence of PNET sarcoma.

Hamatoxyline-eosine x 200.

Conclusion

Extraskeletal bone tumors are tumors

predominantly high-grade tumors (except the facto f myxoid

chondrosarcoma).The treatment includes preoperative

chemotherapy, surgery and postoperative chemotherapy and

radiotherapy in the cases of OS, EW and mesenchymal CHO. CHO was

treated with radical, wide and compartimental margins surgery.

The prevailing

sites of metastasis were the lung and the regional lymph nodes.

No bone metastasis was registered.

Cure may be

achieved by wide or compartimental local excision of the tumor

at an early stage of the disease (combined with radiation and

chemoterapy in the cases of OS, Ewand myxoid CHO).

Myxoid CHO have

better prognosis than synovial CHO and mesenchymal CHO.

In myxoid CHO,

the cells that resemble epithelial cells, can very closely mimic

some malignant breast tumors in thoracic locations.

Differential

diagnosis with extaskeletal chondroma: asymptomatic and harmless

clinical course, the lack of connection between the tumor and

the underlying bone, the slow tumor development, the absence of

sex predominance and the characteristic tumor histological

picture.

Pulmonary

metastasis is not usual in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma,

only two patients have been reported with multiple bone

metastasis.

Biopsy was made

in all cases for punction biopsy with the tru-cut technique.

Extraskeletal

osteosarcoma is the poor type of tumor prognosis (three cases of

exitus, three cases of local recurrence and five cases of lung

metastases).

Additional larger series will be required

before drawing definite conclusions

Reference :

-

Jensen ML, Schumaker B, Jensen OM, Steen JM.

Extraskeletal osteosarcomas: a clinicopathologic study of 25

cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22:588-94.

-

Chung EB, Enzinger FM. Extraskeletal

osteosarcoma. Cancer 1987; 60: 1132-42.

-

Van Rijswijk CSP, Lieng JGSTA, Kroon HM,

Hogendoorn PCW. Retroperitoneal extraskeletal osteosarcoma. J

Clin Pathology 2001; 54:77-78.

-

Lima MA, Rivas LG., Grecco MA, Drumond JM.

Extraskeletal primary osteosarcoma of the frontal region. Rev

Assoc Med Bras 1998; 44: 43-6.

-

Sunil KS, Ammash MN. MD; Edwards WD. MD; Breen

JF. MD; Edmonson J MD. Calcified Left Ventricular Mass: Unusual

Clinical, Echocardiographic, and Computed Tomographic Findings

of Primary Cardiac Osteosarcoma. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2000;

75: 743-747.

-

Cook PA, Murphy MS, Innis PC, Yu JS.

Extraskeletal Osteosarcoma of the Hand. A Case Report. J Bone

Joint Surg Am 1998; 80A: 725-729.

-

Frenourg T, Abel A; Bonaiti-Pellie C, Brugieres

L, Berthet P, Bressac -de Paillerets B, Chevrier A, Chompret A,

Cohen-Haguenauer O, Delattre O, Feingold J, Feunteun J, Frappaz

D, Fricker JP, Gesta P, Jonveaux P, Kalifa C, Lasset C, Leheup

B, Limacher JM, Longy M, Nogues C, Oppenheim D, Sommelet D,

Soubrier F Stoll C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Tristant H. Li-Fraumeni

syndrome: update, new data and guidelines for clinical

management. Bulletin du Cancer 2001; 88:581-7.

-

Konishi E, Kusuzaki K, Murata H, Tsuchihashi Y,

Beabout JW, Unni KK. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma arising in

myositis ossificans. Skeletal Radiology 2001;. 30:39-43.

-

Puzas JE, Miller MD, Rosier RN. Pathologic Bone

Formation. Clin Orthop 1998; 245: 269-279.

-

Alpert LI, Abaci IF, Werthamer S.

Radiation-induced extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer 1973;

31:1359-63..

-

Hasson J, Hartman KS, Milikov E, Mittelman JA.

Thorotrast-induced extraskeletal osteosarcoma of the cervical

region. Report of a case. Cancer 1975; 36:1827-33.

-

Aboulafia AJ, Brooks F, Piratzky J, Weiss S.

Osteosarcoma Arising from Heterotopic Ossification After an

Electrical Burn: A Case Report. J Bone Joint Surg 1999; 81-A:

564-570.

-

Kransdorf MJ, Meis JM. From the archives of the

AFIP. Extraskeletal osseous and cartilaginous tumors of the

extremities. Radiographics 1993; 13: 853-84.C

-

ampanacci M. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors.

Springer-Verlag Wien New York, pp. 1039-1042.

-

Arend SM, Pawels EK, Ardnt JW, Meinders AE.

Extraskeletal localization of the 99m Tc-labeled bone-seeking

tracers in bone scintigraphy. Neth J Med 1994; 45: 177-91.

-

Nielsen GP, Fletcher CD, Smith MA, Rybak L,

Rosemberg AE. Soft tissue aneurysmal bone cyst: a

clinicopathologic study of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;

26:64-9.

-

Nicol KK, Ward WG, Savage PD, Kilpatrick SE.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of skeletal versus extraskeletal

osteosarcoma. Cancer 1998; 8: 176-85.

-

Lee JS, Fetsch JF, Wasdhal DA, Lee BP, Pritchard

DJ, Nascimento AG. A review of 40 patients with extraskeletal

osteosarcoma. Cancer 1995; 76: 2253-9.

-

Gebhardt MC, Parekh SG, Rosemberg AE, Rosenthal

DI. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma of the knee. Skeletal

Radiol 2000; 29: 302-3.

-

Goh YW, Spagnolo DV, Platten M., Caterina P,

Fisher C, Oliveira AM, Nascimento AG. Extraskeletal myxoid

chondrosarcoma: a ligth microscopic, inmunohistochemical,

ultrastructural and inmunostructural study indicating

neuroendocrine criteria. Histopathology 2001; 39: 514-24.

-

Rao L, Kudva R, Rao RV, Kumar B. Extraskeletal

myxoid chondrosarcoma of the chest wall masquerading as a breast

tumor. A case report. Acta Cytol 2002; 46: 417-21.

-

Partham DM. Pathologic case of the month.

Diagnosis and Discussion: Extraskeletal Myxoid Chondrosarcoma

.Archiv Pediat Adolescent Med 1999; 153.

-

Takeda A, Tsuchiya H, Mori Y, Nonomura A, Tomita

K.Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma with multiple skeletal

metastases. J Orthop Sci 2000; 5: 171-4.

-

Patel SR, Burgess MA, Papadopoulous NE.

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: long-term experience with

chemotherapy. Am J Clin Onco 1995; 18: 161-163.

-

Saleh G., Evans HL, Ro JY, Ayala AG.

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study

of ten patients with long-term follow-up. Cancer 1992; 70:

2827-2830.

-

Theodorou DJ, Theodorou SJ, Xenaquis T, Demou S,

Agnantis N, Soucacos PN. Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of soft

tissues of the calf. Am J Othop 2001; 30: 329-32.

-

Suryanarayana KV, Balkrishnan R, Rao L, Rahim

TA. Parapharyngeal space mesenchymal chondrosarcoma in

childhood. Intern J Ped Otorhinolaryngology 1999; 50: 69-72.

-

Takahashi K, Sato K, Kanazawa H, Wang XL, Kimura

T. Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the jaw. Rport of a case and

review of 41 cases in the literature. Head & Neck 1993; 15:

459-64.

-

Ranjan A, Chacko G, Joseph T, Chandi SM.

Intraspinal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. Case report. J Neurosurg

1994; 80: 928-30.

-

Rushing EJ, Mena H, Smirniopoulos JG.

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the cauda equina.Clin Neuropathol

1995; 14:150-3.

-

Luppi G, Cesinaro AM, Zoboli A, Morandi U,

Piccinini L. Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the pleura. Europ

Resp J 1996; 9: 840-3.

-

Lin J, Yip KM, Maffulli N, Chow LT.

Extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the labium majus.

Gynecol Oncol 1996; 60:492-3.

-

Khouja N, Ben Amor S, Jemel H, Kchir N, Boussen

H, Khaldi M. Mesenchymal extraskeletal chondrosarcoma of

the orbit. Report of a case and review of the literature. Surg

Neurol 1999; 52:50-3.

-

Nesi G, Pedemonte E, Gori F. Extraskeletal

mesenchymal chondrosarcoma involving the heart: report of a

case. Italian Heart J 2000; 1: 435-7.

-

Bingaman KD, Alleyne CH Jr, Olson JJ.

Intracranial extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma: a case

report. Neurosurgery 2000; 46:207-11.

-

Kin GE. Kim do K, Park IJ, Ro JY. Mesenchymal

chondrosarcoma originating from the femoral vein. J Vasc Surg

2003; 37: 202-5.

-

Jamal W, Rhys Evans P, Sheppard MN. Mesenchymal

chondrosarcoma of the vagus nerve. J Laryngology & Otology 2002;

116: 644-6.

-

Schorle CM, Unni KK, Aigner T. Neoplastic

chondroneogenesis as a characteristic of mesenchymal

chondrosarcomas. Orthopade 2002; 31:544-50.

-

Naumann S, Krallman PA, Unni KK, Fidler JR,

Bridge JA. Translocation der (13;21)(q10;q10) in skeletal and

extraskeletal mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. Moderm Pathology 2002;

15: 572-6.

-

Park YK, Park HR, Kim YW, Chi SG, Unni KK. Lack

of Bcl10 mutations in malignant cartilaginous tumors. Intern J

Molecular Med 2002; 9:217-9.

-

Sakamoto A, Oda Y, Iwamoto Y, Tsuneyoshi M.

Expression of membrane type 1 matrix metalloprotease, matrix

metalloprotease 2 and tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease 2 in

human cartillaginous tumors with special emphasis on mesenchymal

and dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma. J Cancer Research &

Clinical Oncol 1999; 125: 541-8.

-

Szymanska J, Tarkkanen M, Wiklund T, Virolainen

M, Blomqvist C, Asko-Seljavaara S, Tukiainen E, Elomaa I,

Knuutila S. Cytogenetic study of extraskeletal mesenchymal

chondrosarcoma. A case report. Cancer Genetics &

Citogenetics. 1996; 86:170-3.

-

Castresana JS, Barrios C, Gomez L, Kreicbergs A.

Amplification of the c-myc proto-oncogene in human

chondrosarcoma. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology 1992; 1 :235-8.

-

Bruns J, Elbracht M, Niggemeyer O.

Chondrosarcoma of bone: an oncological and functional follow-up

study. Annals of Oncology 2001; 12:859-64.

-

Taconis WK, van der Heul RO,Taminiau AM.

Synovial chondrosarcoma: report of a case and review of the

literature. Skeletal Radiology 1997; 26: 682-5.

-

Anract P, Katabi M, Forest M, benoit J, Witvoet

J, Tomeno B. Synovial chondromatosis and chondrosarcoma. A study

of the relationship between these two diseases.Rev Chir Orthop

et Reparatrice de l’Appareil Locomoteur 1996; 82:216-24.

-

Bertoni F, Unni KK, Beabout JW, Sim FH.

Chondrosarcomas of the synovium. Cancer 1991; 67: 155-62.

-

Laus M, Capanna R. Synovial chondromatosis and

chondrosarcoma of the hip: indications for surgical treatment.

Italian J Orthop & Traumatol 1982; 8:193-8.

-

Hermann G, Klein MJ, Abdelwahab IF, Kenan S.

Synovial chondrosarcoma arising in synovial chondromatosis of

the rigth hip. Skeletal Radiology 1997; 26: 366-9.

-

King JW, Spujut HJ, Fechner RE, Vanderpool DW.

Synovial chondrosarcoma of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg

1967; 49A: 1389-96.

-

Taras JS, Meadows SE. Synovial chondromatosis in

the radiocarpal joint.Am J Orthop 1995; 24:159-60.

-

Holm CL. Primary synovial chondromatosis of the

ankle. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg 1976; 58 B:878-80.

-

Wenger DE, Sundaram M, Unni KK, Janney CG,

Merkel K. Acral synovial chondrosarcoma. Skeletal Radiology

2002;. 31:125-9.

-

Cheung CC, Kandel AR, Bell RS, Mathews RE,

Ghazarian D. Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma in a 77-year-old woman.

2001;125:

1358-61.

-

Falk S, Alpert M. Five-year survival of patients

with Ewing's sarcoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1967;124:319-324.

-

Bacci G, Ferrari S, Bertoni F, et al. Prognostic

factors in nonmetastatic Ewing's sarcoma of bone treated with

adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:4-11.

-

Hayes FA, Thompson El, Meyer WH. Therapy

for localized Ewing's sarcoma of bone. J Clin Oncol.

1989;7:208-213.

-

Nesbit ME Jr, Gehan EA, Burgert ED Jr.

Multimodal therapy for the management of primary, nonmetastatic

Ewing's sarcoma of bone: a long-term follow-up of the First

Intergroup study. JClin Oncol 1990;8:1664-1674.

-

Snkovics JG, Plager C, Ayala AG, Lindberg RD,

Samuels ML. Ewing sarcoma: its course and treatment in 50 adult

patients. Oncology 1980;37:114-119.

-

Siegel RD, Ryan LM, Antman KH. Adults with

Ewing's sarcoma: an analysis of 16 patients at the Dana-Farber

Cancer Institute. Am J Clin Oncol 1988;11:614-617.

-

Bacci G, Ferrari S, Comandone A. Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy for Ewing's sarcoma of bone in patients older than

thirty-nine years. Acta Oncol 2000;39:111-116.

-

Verrill MW, Judson IR, Wiltshaw E, Thomas A

Harmer CL, Fisher C. The use of paediatric chemotherapy

protocols at full dose is both a rational and feasible treatment

strategy in adults with Ewing's family tumours. Ann Oncol

1997;8:1099-1105.

|