|

*C McLean,

J Oakshott, P Patel, R

Heywood, M Darbyshire and J Pike

*Department of Trauma & Orthopaedics,

Frimley Park MDHU, Frimley, Surrey, UK

Address for Correspondence

Department of Trauma & Orthopaedics, Frimley Park MDHU, Frimley,

Surrey, UK

Email:

christopher.mclean@fph-tr.nhs.uk

|

|

J.Orthopaedics 2005;2(3)e4

Case report

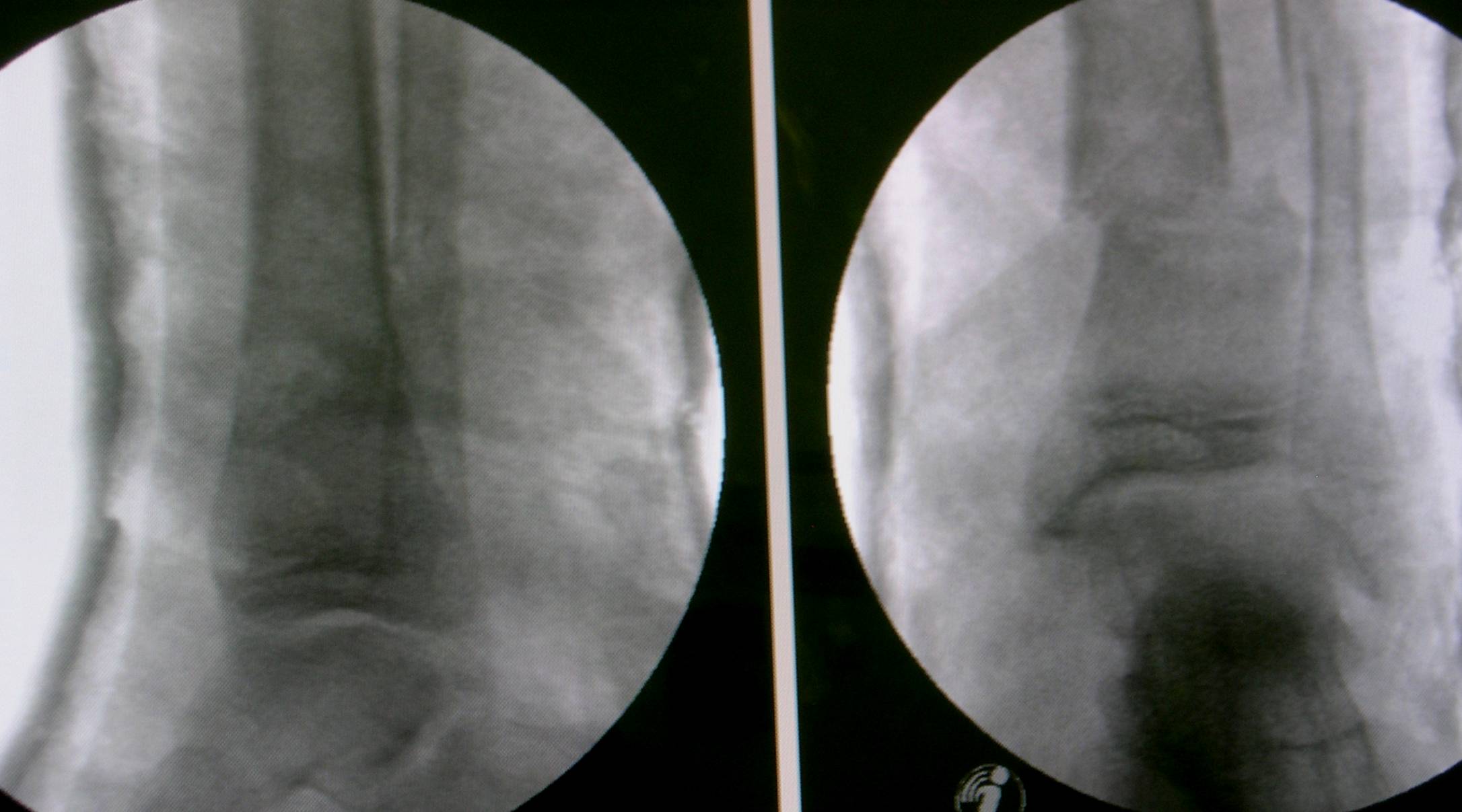

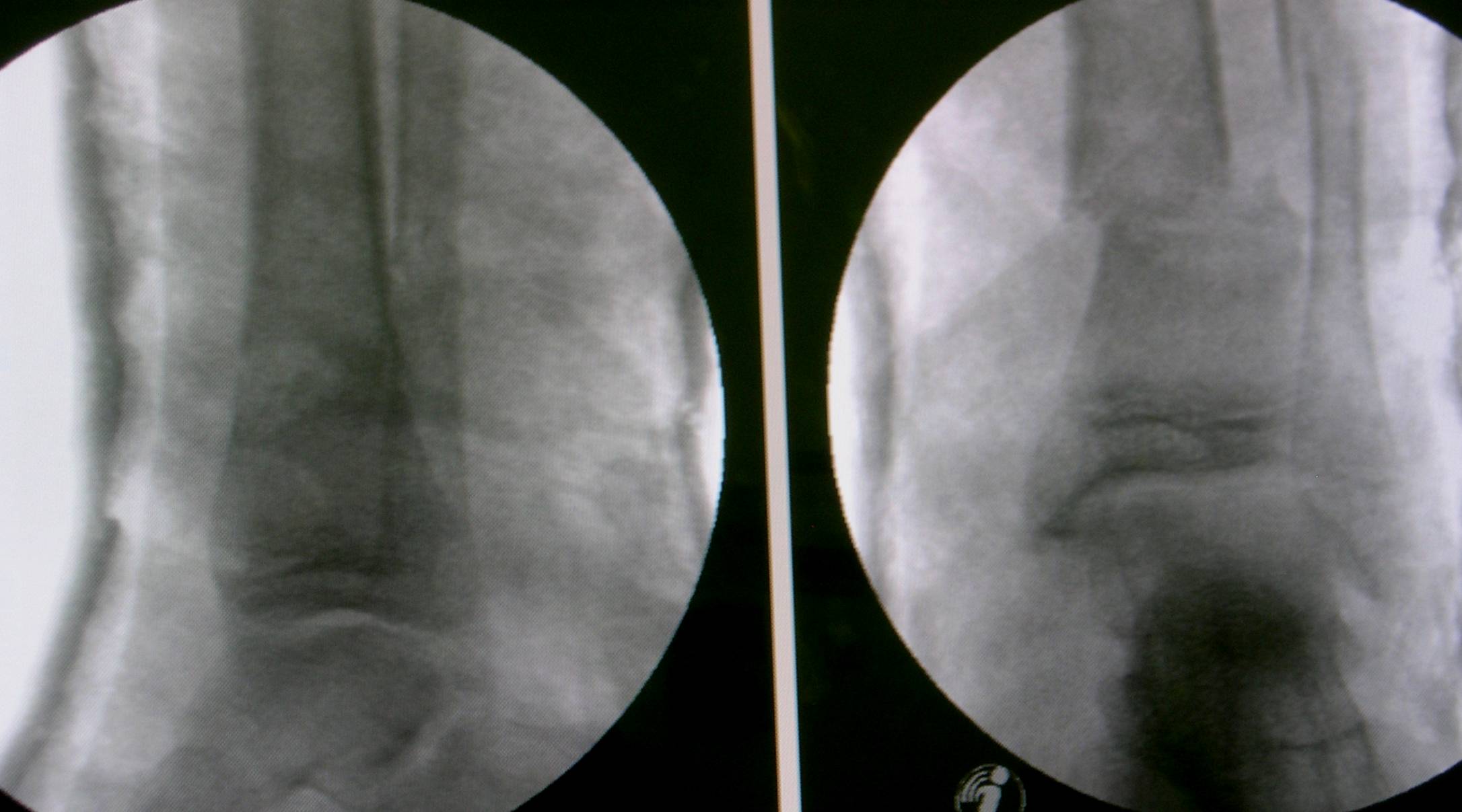

A

thirteen year old adolescent presented to our accident and

emergency department with a closed, displaced fracture of his

metaphyseal distal tibia and fibula. He had fallen from a

height of approximately two metres. He had been

attempting

to jump over a gap between two walls onto attempting

to jump over a gap between two walls onto a ledge on an urban building. Following a sprint run-up he

cleared the gap but overshot the ledge and fell onto his

extended left leg in heel strike. He was taken to hospital and

referred to the on call orthopaedic surgeons approximately two

hours after his injury with a deformed left leg. At that stage

he had diminished sensation to light touch on the dorsum of his

foot and his dorsalis pedis pulse was weaker compared with the

right side. His fracture was reduced emergently in the accident

and emergency department under sedation in order to alleviate

his neurovascular compromise and he was placed into a split

above knee plaster of Paris cast. His neurovascular compromise

was relieved immediately and he remained well overnight. A

formal manipulation under anaesthesia was performed the next

day, when he was appropriately starved and a satisfactory

reduction was achieved. The reduction was not anatomic as the

extent of the impaction of the anterior aspect of the distal

fragment was such that fracture was unstable

a ledge on an urban building. Following a sprint run-up he

cleared the gap but overshot the ledge and fell onto his

extended left leg in heel strike. He was taken to hospital and

referred to the on call orthopaedic surgeons approximately two

hours after his injury with a deformed left leg. At that stage

he had diminished sensation to light touch on the dorsum of his

foot and his dorsalis pedis pulse was weaker compared with the

right side. His fracture was reduced emergently in the accident

and emergency department under sedation in order to alleviate

his neurovascular compromise and he was placed into a split

above knee plaster of Paris cast. His neurovascular compromise

was relieved immediately and he remained well overnight. A

formal manipulation under anaesthesia was performed the next

day, when he was appropriately starved and a satisfactory

reduction was achieved. The reduction was not anatomic as the

extent of the impaction of the anterior aspect of the distal

fragment was such that fracture was unstable readily angulating into both varus or valgus. The best

stability was achieved with the distal fragment translated

approximately twenty percent laterally, in this configuration

the fracture remained anatomically reduced on the lateral film

and there was no angular or rotational deformity. An above knee

plaster of Paris cast was applied with the ankle fully

plantar-flexed in order to control the recurvatum deformity. He

was discharged two days later for follow-up in his local

fracture clinic.

readily angulating into both varus or valgus. The best

stability was achieved with the distal fragment translated

approximately twenty percent laterally, in this configuration

the fracture remained anatomically reduced on the lateral film

and there was no angular or rotational deformity. An above knee

plaster of Paris cast was applied with the ankle fully

plantar-flexed in order to control the recurvatum deformity. He

was discharged two days later for follow-up in his local

fracture clinic.

Discussion

Fractures of the metaphyseal distal tibia and fibula are not

common fractures in children being only the third most common

long bone to fracture. According to Rockwood ankle fractures,

including the metaphyseal distal tibia, account for 4.4% of all

paediatric fractures. These fractures are often greenstick. In

contrast our patient’s fracture was one hundred percent

displaced as a result of the comparatively violent mechanism of

injury he sustained. The violence of his injury accounted for

his initial deformity, subsequent impaction of the anterior

aspect of his distal fragment and consequential non-anatomic

reduction. Nevertheless adequate stability was achieved without

the need for percutaneous pins. Our patient’s skeleton is close

to maturity and in keeping with his adolescent status his

fracture had a combination of adult and paediatric features. He

was a high school student participating in an unorganised

physical activity – this combination is associated with a high

incidence of sport related injury [5]. His fracture occurred in

the lower limb as opposed to the upper limb. Upper limb

injuries are more typical for children as they have a tendency

to fall head first and land on their upper limbs or skulls

[2,3]. The injury risk factor for Parkour is unknown Chambers

defined this concept in a study of six American sports in 1979.

He studied the risk factors that contributed to fractures and

dislocations during athletic events. The injury risk factor was

a function of the number of injuries, number of participants,

duration of the participation and the duration of the sporting

season [1]. Our patient had been attempting to perform an

acrobatic leap as part of a Parkour activity. Parkour may also

be known, as the art of movement, free-running, or obstacle

coursing is an activity invented in the Paris’ suburbs by David

Belle and Sebastien Foucan. Parkour consists of finding new and

potentially dangerous ways to traverse the city landscape. The

activity is a way of using obstacles in one’s path in order to

perform jumps and acrobatics. It involves the scaling of walls,

roof-running and leaping from building to building. In essence

it can be thought of as an extreme sport that combines aspects

of free hand rock climbing with gymnastics in an urban setting.

Enthusiasts of the activity may refer to themselves as

Parkouristes or traceurs. Some Parkour enthusiasts claim that

the activity is not just a recreation rather it is a form of art

or even akin to an eastern philosophy requiring discipline,

self-improvement and interdependence. Parkour beginners are

encouraged to start with the basic manoeuvres, in groups,

avoiding high walls and with the use of protective equipment.

Information regarding Parkour is readily available on the

internet, a search using the google search-engine revealed over

73,000 matches. Our patient was new to Parkour, having gained

his first exposure to it two days before his injury in a

television documentary he had watched. As such he was

performing a difficult jump, on an unfamiliar obstacle – he was

on a visit to our hospital’s locality – without the use of any

protective equipment and without any previous Parkour training.

The phenomenon of children participating in dangerous television

inspired activity is well known. Children who watch television

depicting physical risk taking are more likely to take physical

risks themselves [4]. Whilst there are no other reports of

injuries sustained during Parkour mentioned in the medical

literature, it is surely only a question of time before a

substantial number of case series are described. Consequently

traumatologists should familiarise themselves with Parkour and

its risks and advise those wishing to participate in the

activity of the inherent dangers associated with the recreation

and means by which these may be reduced.

REFERENCES

1) Chambers R. Orthopaedic

Injuries in Athletes Ages 6 to 17: Comparison of Injuries

Occurring in Six Sports. American Journal Sports Medicine 7:

195, 1979.

2) Hanlon C, and Estes W. Fractures in Childhood—A Statistical

Analysis. American Journal of Surgery 87: 312, 1954.

3) Iqbal Q. Long-Bone Fractures Among Children in Malaysia.

International Surgery 59: 410, 1975.

4) Potts R, Doppler M, Hernandez M. Effects of television on

physical risk taking in children. Journal of Experimental Child

Psychology 58: 321-331, 1994

5) Zaricznyj B, Shattuck L, Mast T, Robertson R,

and D'Elia G. Sports-Related Injuries in School-Aged Children.

American Journal Sports Medicine 8: 318, 1980.

|

attempting

to jump over a gap between two walls onto

attempting

to jump over a gap between two walls onto a ledge on an urban building. Following a sprint run-up he

cleared the gap but overshot the ledge and fell onto his

extended left leg in heel strike. He was taken to hospital and

referred to the on call orthopaedic surgeons approximately two

hours after his injury with a deformed left leg. At that stage

he had diminished sensation to light touch on the dorsum of his

foot and his dorsalis pedis pulse was weaker compared with the

right side. His fracture was reduced emergently in the accident

and emergency department under sedation in order to alleviate

his neurovascular compromise and he was placed into a split

above knee plaster of Paris cast. His neurovascular compromise

was relieved immediately and he remained well overnight. A

formal manipulation under anaesthesia was performed the next

day, when he was appropriately starved and a satisfactory

reduction was achieved. The reduction was not anatomic as the

extent of the impaction of the anterior aspect of the distal

fragment was such that fracture was unstable

a ledge on an urban building. Following a sprint run-up he

cleared the gap but overshot the ledge and fell onto his

extended left leg in heel strike. He was taken to hospital and

referred to the on call orthopaedic surgeons approximately two

hours after his injury with a deformed left leg. At that stage

he had diminished sensation to light touch on the dorsum of his

foot and his dorsalis pedis pulse was weaker compared with the

right side. His fracture was reduced emergently in the accident

and emergency department under sedation in order to alleviate

his neurovascular compromise and he was placed into a split

above knee plaster of Paris cast. His neurovascular compromise

was relieved immediately and he remained well overnight. A

formal manipulation under anaesthesia was performed the next

day, when he was appropriately starved and a satisfactory

reduction was achieved. The reduction was not anatomic as the

extent of the impaction of the anterior aspect of the distal

fragment was such that fracture was unstable readily angulating into both varus or valgus. The best

stability was achieved with the distal fragment translated

approximately twenty percent laterally, in this configuration

the fracture remained anatomically reduced on the lateral film

and there was no angular or rotational deformity. An above knee

plaster of Paris cast was applied with the ankle fully

plantar-flexed in order to control the recurvatum deformity. He

was discharged two days later for follow-up in his local

fracture clinic.

readily angulating into both varus or valgus. The best

stability was achieved with the distal fragment translated

approximately twenty percent laterally, in this configuration

the fracture remained anatomically reduced on the lateral film

and there was no angular or rotational deformity. An above knee

plaster of Paris cast was applied with the ankle fully

plantar-flexed in order to control the recurvatum deformity. He

was discharged two days later for follow-up in his local

fracture clinic.