|

Abstract:

Introduction:

unicompartmental knee replacement (UKR) is a popular alternative

to total knee replacement (TKR) in medial compartment disease.

Revision to TKR is well described as a late endpoint.

Our objective is to investigate early surgical management

of persistent pain following UKR, identify common themes and

effectiveness of re-interventions.

Methods:

381 UKRs implanted over 5 years included, and patients requiring

re-operation reviewed retrospectively.

Findings:

27 re-interventions performed on 17 patients at a mean 16.8

months (95% CI 9.5 to 24.1), with symptom onset post-operatively

at 9 months (95% CI 4-14). There were 10 arthroscopies, 10

revisions to TKR, 4 manipulations under anaesthesia (MUA), 2

bearing exchanges, and 1 tibial-plateau fracture fixation. MUA

improved stiffness 2 of 3 patients. Arthroscopy was successful

in 2 patients with loose cement-bodies, not providing a

diagnosis in 8, of whom 7 required subsequent revision. Overall

there were 10 revisions: 9 were performed for persistent pain

and 9 reported symptom improvement. Intra-operative findings

included aseptic loosening (n=4), synovitis (n=2), increased

posterior slope of the tibial cut (n=1), dislocated bearing

(n=1), and no cause of failure (n=2). There were no deep

infections.

Conclusions:

Our unit’s early re-intervention rate is 4.5% (95% CI 2.4 to

6.5), with a revision rate of 2.6% (95% CI 1.0 to 4.2) after a

mean (±SD) follow-up of 40 (±16) months. Arthroscopy is a poor

diagnostic and therapeutic option against persistent pain

following UKR. In contrast, the decision to revise, although

initially disappointing for both patient and surgeon, gave

symptom improvement in 90%.

J.Orthopaedics 2010;7(3)e5

Keywords:

Introduction:

The mobile bearing unicondylar knee replacement (UKR) was

developed in 1978, with the first Oxford partial knee

arthroplasty performed in 1982.1 Survival at ten

years is quoted at 98% (95% CI 93% to 100%) by the design group2

and 95% (95% CI 90.8% to 99.3%) quoted by an independent study.3

These excellent long term results have encouraged an increased

use of this implant for unicompartmental arthritis of the knee

in recent years.4

The Oxford group suggest one in three of all knees requiring

arthroplasty are suitable for a UKR,5 despite this

only approximately 8% of all knee arthroplasties are

unicompartmental replacements.4 This may be because

there is concern following UKR of persistent or new onset

post-operative pain. The pain could indicate an incorrect

initial choice of implant, disease progression to unresurfaced

compartments, aseptic loosening or infection.4

Further management of this group of patients presents a clinical

dilemma, especially if laboratory and radiological

investigations do not highlight a potential cause for their

symptoms. Conservative measures are usually recommended to

patients, with advice that the symptoms are likely to settle

with time or that the symptoms are not amenable to surgical

intervention. This reflects the established management of

similar pain following total knee replacement (TKR).6

Despite these reassurances there are a small number of

patients who consider their symptoms debilitating enough to

warrant further surgery.

The Royal Orthopaedic Hospital (Birmingham) is a specialised

Orthopaedic tertiary referral centre in the United Kingdom

dealing with a large throughput of arthroplasty patients, and

having on-site dedicated knee arthroplasty surgeons as well as

orthopaedic nurses and physiotherapists. The objectives of this

study are to establish early re-operation rates following UKR

and assess the results of subsequent operative intervention in

patients with debilitation pain following primary UKR.

Materials

and Methods:

All Phase 3 Oxford UKRs (Biomet, Bridgend, UK) implanted at our

institution between November 2002 and December 2007 were

included in the study. 40 patients underwent bilateral surgery.

Surgery was performed under the supervision of seven consultant

arthroplasty surgeons as described in the manual of surgical

technique.7 Patients who required any subsequent

surgery on the ipsilateral knee were highlighted retrospectively

using our proprietary database, and their medical notes

individually reviewed.

Results :

383 UKRs were performed on 343 patients over this five year

period, with a mean (±SD) follow-up of 40.1 months (±16 months).

Two patients were excluded as they underwent simultaneous ACL

reconstruction leaving a cohort of 381 UKRs.

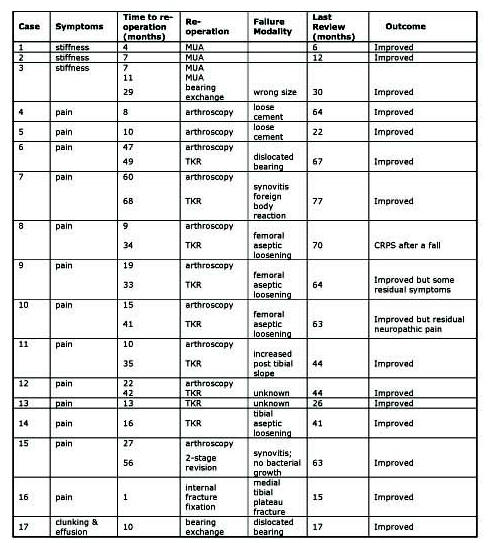

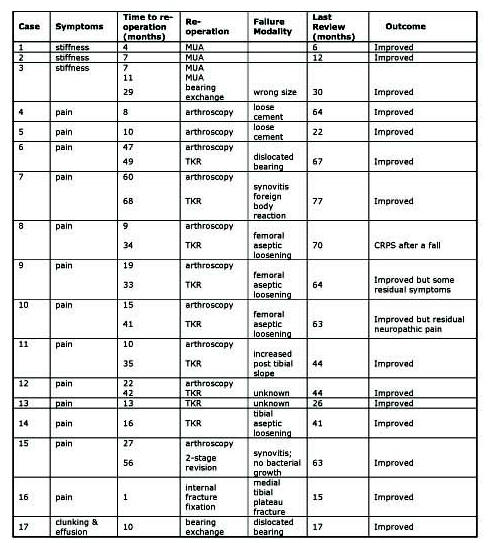

There were 27 re-operations performed in 17 patients [see table

1], equivalent to a re-intervention rate of 4.5% (95% CI 2.4 to

6.5). The mean time to the first re-operation was 16.8

months (95% CI 9.5 to 24.1) from the primary procedure.

Procedures undertaken were: 10 revisions to total knee

replacements (1 performed in two stages), 10 arthroscopies, 4

manipulations under anaesthetic (MUA), 2 exchange of mobile

bearings and 1 open reduction internal fixation of a tibial

plateau fracture.

Manipulation under anaesthetic

Three patients with ongoing limited range of movement were

manipulated. Satisfactory range of movement was achieved for

two patients. Despite two manipulations the final patient did

not improve until the mobile bearing was exchanged for a smaller

component. This resulted in a satisfactory outcome.

Table 1:

Summary of patients requiring re-intervention

Arthroscopies

Ten patients were managed with arthroscopic procedures, but only

two (20%) had significant resolution of their symptoms. In both

these cases loose cement fragments were seen in post-operative

radiographs and arthroscopic removal settled their symptoms.

Arthroscopic assessment of the remaining eight patients revealed

no gross loosening of the implants when probed and no gross

disease progression. One patient was noted to have lateral

partial thickness fissuring in the lateral compartment, while

four patients had evidence of early patello-femoral wear. All

eight were subsequently revised to total knee replacements, with

symptom improvement in seven. Mean interval between arthroscopy

and revision was 17.1 months (95% CI 10.1 to 24.1).

Revision

to total knee replacement

In total ten UKRs were revised to total knee replacements, eight

as previously discussed were following initial arthroscopic

surgery, and two following radiographic suspicion of aseptic

loosening. Mean time from primary UKR to revision was

38.2 months (95% CI 28.1 to 48.3). Aseptic loosening of

the components was demonstrated intraoperatively in four

patients (3 in the femoral component and 1 in the tibial

component). In those UKRs with stable implants, intraoperative

findings included: synovitis with histology consistent with a

prominent foreign body reaction (n=2), and increased posterior

slope of the tibial cut (n=1). No clear cause was identified in

two patients.

Nine of the ten revisions were single-stage procedures. The

only two-stage revision was initially planned as a one stage

revision but converted after intra-operative findings of

widespread haemosiderin deposits. Subsequent microbiological

and histological investigations excluded infection. A primary

prosthesis was implanted in eight cases (7 AGCs Biomet, Bridgend

UK & 1 Kinemax Stryker Howmedica ), and a revision

implant with 10mm medial augments was required in two patients

for associated bone loss (Maxim Biomet, Warsaw, IN). There were

no revisions for infection.

Amongst the ten patients revised for ongoing pain nine had a

significant improved in symptoms, with complete resolution of

symptoms in seven. One patient had non-specific ongoing

symptoms whilst another complained non-dermatomal pain. Both

considered these symptoms acceptable. The final patient with a

poor outcome had an encouraging improvement in symptoms

initially, but after a fall within eight weeks of his revision

developed symptoms consistent with complex regional pain

syndrome.

The early re-operation rate following Oxford unicompartmental

knee replacement in our unit is 4.5% (95% CI 2.4 to 6.5),

with a revision rate of 2.6% (95% CI 1.0 to 4.2) after a mean (±SD)

follow-up of 40.1 (±16) months.

Discussion :

The ideal indication for unicompartmental knee replacement is

“anteromedial arthritis”.8 Clinically this equates

to an intact anterior cruciate ligament, varus deformity that is

correctable at 20° flexion, functionally normal medial

collateral ligament and full thickness cartilage in the lateral

compartment. Chondral ulcers on the medial aspect of the

lateral femoral condyle and patellofemoral arthritis are not

considered contraindications by the Oxford group.9

The Oxford group state that using the above criteria, 1 in 3

knees suitable for arthroplasty are appropriate for their

implant.5 The current phase III Oxford implant was

introduced in 1998 and is implanted using minimally invasive

techniques. In the Oxford knee this is associated with half the

recovery time of the full arthrotomy, and one-third the recovery

time of a total knee arthroplasty.10

Despite the encouraging results with the Oxford unicompartmental

knee replacement (UKR) only 8% of all primary knee arthroplasty

are unicompartmental, of which 72% are the Oxford phase III

implant.4 There are a combination of design,

philosophical and clinically-related reasons that some surgeons

limit their own indications for the implantation of a

unicompartmental knee replacement. Technically, unicompartmental

arthroplasty is more challenging than a total arthroplasty as

exact soft tissue balancing is required.11 The

addition of a mobile bearing to the Oxford design, with the

potential for dislocation, reduces the margin for error

further. Studies have shown that technical errors are the main

cause of early failure, long term studies have shown that if

survival is good at seven years then long term results are

likely to be good.10 This pattern of failure is

unique to congruent mobile bearing designs as wear rates are

low, which appears to have resulted in improved long term

results in comparison to other designs.2

The potential problem of persistent postoperative pain, with its

subsequent management challenges, has also raised concerns.

Failure to fully resolve all symptoms following a TKR is also

well recognised and once infection, aseptic loosening and gross

malalignment are excluded it is usually managed conservatively.

This course of action is realistically harder to follow in any

form of partial replacement, as the potential always exists for

further surgery to the unresurfaced components. However,

conservative measures are still usually recommended to

recipients of a UKR as they are to their TKR counterparts, with

advice that the symptoms are likely to settle with time or that

the symptoms are not amenable to surgical intervention.

Despite these reassurances there are a small number of patients

who consider their symptoms debilitating enough to warrant

further surgery. Clinically this group is often difficult to

manage appropriately.

The source of the persistent debilitating symptoms is not always

clear despite clinical examination, serial laboratory and

radiological investigations. In our specialist unit the

preferred primary re-operation chosen for persistent pain was

knee arthroscopy. Symptom improvement was only achieved in 2

out of 10 patients, both of whom had a clear pre-arthroscopy

diagnosis of loose cement fragments. In the remaining patients

symptoms did not improve significantly enough to prevent

revision to a TKR. Arthroscopic assessment further failed to

identify loose prostheses that were apparent at the time of

revision. Our findings would suggest that the role of

arthroscopy is limited in the management of a painful UKR as it

is a poor diagnostic and therapeutic modality.

The decision to revise to a total knee replacement is never

straightforward, for the patient it involves further major

surgery with no guarantee of symptom resolution and for the

surgeon it confirms failure of the original UKR. This difficult

decision is demonstrated in the mean 17-month interval between

the initial arthroscopy and subsequent revision. Despite these

misgivings our results are encouraging, with nine (90%) of

patients revised to TKR achieving clinically significant symptom

improvement, of which seven (70%) are pain free. Aseptic

loosening was the most consistent intra-operative finding

identified in four patients. The bone loss associated with

loosening was minimal, and only two cases required a revision

implant. Our findings would suggest that although the decision

to revise is initially disappointing there is a marked

improvement in symptoms.

Pandit5 reviewed 688 consecutive Oxford knee

replacements from the Oxford group: there were eight (1.2%)

revisions within 2.5 years of the index procedure and seven

other re-operations identified over an unspecified time period.

Indications for revision were infection in four cases, two

dislocated bearings and two for unexplained pain. Despite

revision surgery, pain persisted in one of these patients.

Re-operation was required for stiffness in four cases, pain

resulted in arthroscopy in two patients and one patient

underwent debridement for a superficial infection. It is not

clear from their data if the patients that were formally revised

to a total knee replacement underwent other procedures prior to

revision. Extrapolating their data, the presumed “best-case”

scenario for early re-operation is fifteen cases (2.2%) with a

revision rate of 1.2%.

Svärd’s3

series of 103 Oxford replacements identified three revisions

(2.9%) and one re-operation (0.9%) within two years of the index

procedure. The indications for revision were pain and clinical

suspicion of infection respectively. The re-operation was for a

suspected loose body, this was not located but symptoms

improved. No mention was made in the paper with respect to

complications of stiffness and the requirement for manipulation

under anaesthetic. Again it is not clear from their data if the

patients that were formally revised to a total knee replacement

underwent other procedures prior to revision. Extrapolating

their data the presumed “best-case” scenario for early

re-operation is four cases (3.8%) with a revision rate of 2.9%.

Reviewing the outcome of 381 Oxford knee replacements in

our institution, seventeen (4.5%) patients required

re-operations for persistent symptoms. In ten (2.6%)

patients a decision was been made to revise the primary implant

to a total knee replacement.

Our figures are higher than the extrapolated “best-case”

scenario data published from the design centre in Oxford5

(2.2% and 1.2%) and broadly comparable with the independent

series published by Svärd3 (3.8% and 2.9%).

Conclusions:

4.5% (95% CI 2.4% to 6.5%) of patients required a re-operation

for ongoing symptoms following an Oxford UKR. Our revision rate

is 2.6% (95% CI 1.0% to 4.2%), which is comparable to current

published data. Management of debilitating pain following

unicondylar knee surgery can be difficult. Arthroscopy is a

poor diagnostic and therapeutic modality for this clinical

problem, and only recommended if a correctible problem is

identified clearly prior (e.g. a loose body). Our results

suggest that if appropriate conservative measures have failed,

persistent pain is managed most reliably with revision to a

total knee replacement.

Reference:

-

Goodfellow J, O’Connor J.

The mechanics of the knee and prosthesis design. J Bone

Joint Surg (Br), 1978; 60-B:358-369

-

Murray D, Goodfellow J, O’Connor J.

The Oxford medial unicompartmental arthroplasty – a ten year

survival study. J Bone Joint Surg (Br), 1998; 80-B

(6):983-989

-

Svärd U, Price A.

Oxford medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. A survival

analysis of an independent series. J Bone Joint Surg (Br),

2001; 83:191-194

-

National Joint Registry for England and Wales 5th

annual Report 2008

-

Pandit H, Jenkins C, Barker K, Dodd C, Murray D.

The Oxford medial unicompartmental knee replacement using a

minimally-invasive approach. J Bone Joint Surg (Br), 2006;

88-B:54-60

-

Elsom DW, Brenkel IJ.

A Conservative approach is feasible in unexplained pain after

knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br), 2007; 89-B:1042-1045

-

Oxford™ Unicompartmental Knee: Manual of the Surgical

Technique, Biomet UK Ltd (UK)

-

White S, Ludkowski P, Goodfellow J.

Anteromedial osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg

(Br), 1991; 73-B:582-586

-

D. J. Beard, H. Pandit, H. S. Gill, D. Hollinghurst, C. A. F.

Dodd, D. W. Murray.

The influence of the presence and severity of pre-existing

patellofemoral degenerative changes on the outcome of the

Oxford medial unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone

Joint Surg Br, Dec 2007; 89-B: 1597 - 1601.

-

Price A, Webb J, Topf H, Dodd CA, Goodfellow JW, Murray DW.

Rapid Recovery after Oxford unicompartmental arthroplasty

through a short incision. J Arthroplasty, 2001; 16:970-976

-

Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, Lidgren L.

The routine of surgical management reduces failure after

unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br,

2001, 83(1):45-4

|