|

Abstract:

Objective: Determine the practices of South Asian Association of

Regional Cooperation (SAARC) knee surgeons with at least 5 years

of ACL reconstruction experience.

Methods: A 15-item survey

was distributed at the Fourth SAARC Orthopaedic Association

Conference.

Results: Fourteen surgeons representing five SAARC

countries (70% of eligible attendees) completed and returned the

survey. Most (42.9%) performed 10-25 ACL reconstructions/year.

The primary graft used was a bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB)

autograft (57.1%). Most (50%) used a BPTB autograft >

95% of the time and a hamstring autograft < 5%, while 43%

used a hamstring autograft > 80% of the time and a BPTB

autograft < 20%. The primary tibial (85.7%) and femoral

(57.1%) fixation was interference screws. Most (62.5%) released

BPTB autograft patients back to sports at six months

post-surgery. An equal percentage (50%) released hamstring

autograft patients back to sports at six or nine months

post-surgery. Most (57.1%) did not perceive a benefit changing

to an anatomical double bundle ACL reconstruction. Concerns

were expressed about patients presenting later following index

ACL injury with more associated injuries, referring physicians

providing incomplete information, fewer surgical options due to

limited resources, the need to improvise techniques, more

frequent post-surgery hospitalization, and the need for more

educational and technology information exchanges. Conclusions:

Most experienced SAARC surgeons performed < 50 ACL

reconstructions/year with increasing hamstring autograft use.

Concerns were expressed regarding the need for additional

resources, for improved educational and technology information

exchanges, and for earlier referral with improved

documentation. Further study with greater subject numbers and

representation from all SAARC countries is needed.

J.Orthopaedics 2010;7(2)e2

Keywords:

knee; arthroscopy; survey

Background:

The South Asian

Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was created in

response to economic and societal adversities experienced by

South Asian nations.1,2 The leaders of state from

seven nations, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal,

Pakistan and Sri Lanka adopted the original SAARC charter in

1985. In 2007, Afghanistan was formally introduced as a full

member. Committees have been established by SAARC to facilitate

seven areas of development: Agriculture-rural issues, science

technology-meteorology, health-population activities,

transportation, women-youth-children issues, human resource

development, and environment-forestry.1,2

Anterior cruciate

ligament (ACL) injuries of the knee and their sequelae are a

global healthcare concern among active individuals, particularly

females.3,4 Additionally, surgical and

rehabilitation management for this condition remain somewhat

controversial.5 Compared to Western medical

literature few reports have addressed issues related to the ACL

reconstruction and rehabilitative practices specific to SAARC

countries. Our literature search revealed that all previously

published reports come from one SAARC member nation, India.6-8

Clinical medicine as it relates to

health-population activities and SAARC standard practices,

surgical and patient outcomes following ACL injury,

reconstruction, and rehabilitation have not been previously

reported. The purpose of this pilot descriptive study was to

identify the ACL reconstruction and rehabilitation practices of

experienced SAARC knee surgeons. It is our intent that this

work will help develop prospective multi-center studies.

Materials and Methods:

A 15-item survey was

distributed at the Fourth SAARC Orthopaedic Association

Conference held in Kathmandu, Nepal to surgeons that

specialized in knee arthroscopy and who had been performing ACL

reconstruction for a minimum of five years. A departmental

ethics review board approved this study. After providing

demographic data including country of residence and age,

surgeons answered multiple choice questions regarding the number

of ACL reconstructions performed annually, how long after the

index injury ACL reconstruction was generally performed, the

primary ACL reconstruction graft choice, how many months

following ACL reconstruction the patient was allowed to return

to sports, and if prescribed for what length of time functional

knee braces were used.

Fill in the blank type

questions identified surgeon practices for current and

historical ACL reconstruction graft use (bone-patellar tendon

bone, doubled hamstring tendon, quadrupled hamstring tendon,

quadriceps tendon, or allograft), preferred ACL graft fixation

method, perceptions of how current ACL reconstruction and

treatment practice differ from current Western country practices

based on medical journals, web-based medium, or direct

observations, and on what they deem to be important for Western

country peers and companies to know about ACL reconstruction in

their country. Lastly, fill in the blank type questions were

used to identify whether or not knee braces were routinely

prescribed following ACL reconstruction, if they perceived any

advantage in changing to an anatomical double bundle ACL

reconstruction technique, and if so, to describe the ideal

patient for this technique.

Descriptive statistical analysis (SPSS

version 11.0, Chicago, IL, USA) was performed using Chi-Square

or Fisher’s Exact tests (when Chi-Square test assumptions were

not met) for categorical data comparisons. An alpha level of p

< 0.05 was selected to indicate statistical significance.

Results:

From approximately 200

hundred conference attendees, 35 surgeons were identified that

primarily performed knee arthroscopy. Of these attendees 20 had

been performing arthroscopic ACL reconstruction for a minimum of

five years prior to survey completion. Fourteen surgeons from

five SAARC countries (India = 5, Nepal = 4, Bangladesh = 2,

Pakistan = 2, and Bhutan = 1) completed the survey for a 70%

(14/20) return rate from eligible conference attendees. Surgeon

age (mean ± standard deviation) was 43.4 ± 10.4 years (range =

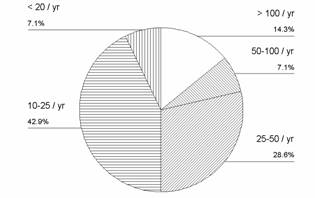

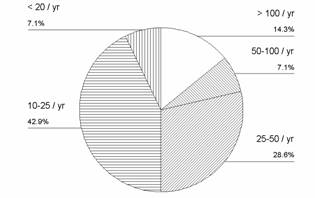

30-71 years). Most (42.9%) performed 10-25 ACL

reconstructions/year (Fig. 1).

Fig.1. Number

of ACL reconstructions performed/year by experienced SAARC knee

surgeons.

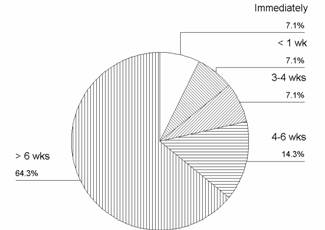

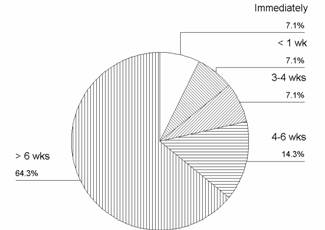

Most

performed ACL reconstruction surgery at more than six weeks

post-injury (64.3%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Time period between index ACL injury and

surgery.

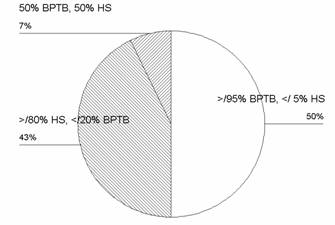

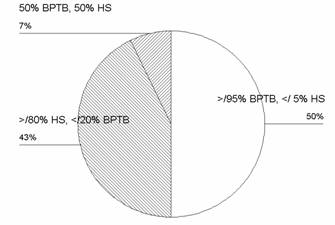

The primary graft

selected for ACL reconstruction was a bone-patellar tendon-bone

(BPTB) autograft (57.1%), with 42.9% choosing hamstring

autografts. Slightly more respondents used a BPTB autograft

> 95% of the time and a hamstring autograft < 5%

(50%) than used a hamstring autograft > 80% of the time

and a BPTB autograft < 20% (43%)(Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Current ACL reconstruction graft preference (BPTB = bone-patella

tendon-bone autograft; HS = hamstring autograft) of experienced

SAARC knee surgeons.

Two experienced surgeons

that had recently changed their primary ACL reconstruction graft

preference switched from either 100% BPTB autograft or 75% BPTB

autograft and 25% double strand hamstring graft use to greater

use of two or four strand hamstring autografts. The primary

method of tibial (85.7%) and femoral (57.1%) graft fixation was

interference screws. The second most frequent femoral fixation

method was endo-buttons (35.7%) and the second most frequent

tibial fixation method was a screw-post combination (7.1%). The

most frequent time of release to unrestricted activities of

daily living for BPTB autograft patients was 5-6 months (37.5%)

followed by 10-12 months (25%), 3-4 months (25%), and 1-2 months

(12.5%). The most frequent time of release to unrestricted

activities for hamstring autograft patients was 7-9 months

(66.7%), 5-6 months (16.7%) and 1-2 months (16.7%). The time of

release to unrestricted activities of daily living between graft

types did not display statistically significant differences

(Fisher’s Exact Test = 3.2, p = 0.61). Most surgeons released

patients with a BPTB autograft (62.5%) back to sports at six

months post-surgery followed by nine months post-surgery (25%)

and > 12 months post-surgery (12.5%). Surgeons were equally

divided (50%) for releasing patients with a hamstring autograft

back to sports either at six or nine months post-surgery. The

timing of release back to sports did not display statistically

significant differences between graft types (Fisher’s Exact

Test = 1.4, P = 0.77). Most surgeons (57.1%) did not routinely

prescribe a functional knee brace post-surgery. Of those who

prescribed knee braces, most (60%) recommended use for less than

six months post-surgery while 40% recommended their use for six

months – one year. Experienced knee surgeons from India were

more likely to prescribe a functional knee brace post-surgery

(80%, 4 of 5 surgeons) than experienced knee surgeons from the

other SAARC countries (22.2%, 2 of 9 surgeons). Most surgeons

(57.1%) did not perceive a substantial benefit in changing from

their current ACL reconstruction method to use of an anatomical

double bundle ACL reconstruction technique. Surgeons who

believed that a benefit would exist believed that it would be

most advantageous for high re-injury risk athletes such as

competitive soccer players and revision cases.

Perceived ACL

reconstruction practice differences compared to Western

countries based on what surgeons had observed in Western

journals, web-based medium, or travels, included, fewer surgical

options due to limited facility, equipment and implant

availability (Bangladesh), a widespread need to improvise

surgical techniques (Pakistan), a higher percentage of male

cases (India), fewer opportunities for revision surgery with the

athlete remaining active in sports (India), the need for 2-3 day

post-surgery hospitalization (Nepal), and patients tending to

present for treatment later following the index ACL injury with

a greater number of associated injuries (India, Nepal).

Surgeons who provided comments as to what they believed their

peers and companies in Western countries should know about ACL

reconstruction in their country suggested that many patients

present to them a considerable time period following the index

ACL injury (Pakistan), there is often poor or inaccurate

documentation from the referring general care physician

regarding the patient’s injury history (India), limited

facility, equipment, and implant resource availability (Nepal),

the belief that comparable patient outcomes can be achieved

despite existing facility and other patient care difficulties

(Nepal), the effectiveness of simple, inexpensive knee braces

(India) and the need for more arthroscopic and sports medicine

education and technology information transfer and fellowship

experiences (India).

Discussion :

A similar percentage of

SAARC knee surgeons selected BPTB and hamstring autografts for

ACL reconstruction. This is not surprising given the history of

similar patient outcome effectiveness between these graft types9

and the growing trend toward greater hamstring autograft use.10

Additionally, the majority of respondents performed < 50 ACL

reconstructions/ year, which also is comparable to Western

country practices.11,12 Knee surgeons in Western

countries often prescribe functional knee braces following ACL

reconstruction to prevent graft strain, decrease pain, improve

knee extension range of motion and restrict end range movements

to facilitate graft healing. In a systematic review that

assessed knee joint range of motion, ACL graft laxity, knee pain

level, and re-injury risk however, Wright et al13

reported that none of these variables were influenced by knee

brace use following ACL reconstruction. The more restricted use

of functional knee braces by experienced SAARC knee surgeons

suggests a better use of limited resources, particularly given

the limited evidence supporting the efficacy of regular

functional knee brace use. Perhaps knee surgeons in Western

countries should re-examine their routine prescription of

expensive custom or “off the shelf” knee braces following ACL

reconstruction given this limited evidence. Two experienced

SAARC knee surgeons (India, Pakistan) recommended that

short-term use of simple, inexpensive knee braces was

sufficient.

A growing number of knee

surgeons are attempting to more closely replicate native ACL

function via the use of anatomical double bundle ACL

reconstruction techniques. This trend is occurring

despite the considerable body of evidence that supports

conventional ACL reconstruction methods and the limited evidence

for improved patient outcomes that exist supporting anatomical

double bundle ACL reconstruction. Most experienced

SAARC knee surgeons did not believe that anatomical double

bundle ACL reconstruction would provide a significant advantage

over conventional single bundle ACL reconstruction methods.

Those who did suggested that sportsmen such as competitive

soccer athletes and revision cases would benefit most.

Surgeon perceptions regarding what

they deemed important that Western country knee surgeons and

companies should know about ACL reconstruction in their country

differed somewhat based on the SAARC country of origin. For

example, experienced knee surgeons from Nepal, Pakistan,

Bangladesh, and Bhutan expressed greater concerns related to

limited medical resource availability, the need to more

frequently improvise or modify surgical techniques, and the more

common need for post-surgery hospitalization. In contrast,

experienced knee surgeons from India more commonly expressed

concerns related to the need for arthroscopy and sports medicine

educational information and technology exchanges. In contrast

to knee surgeons in India who seek technique refinement and

updates, knee surgeons in other SAARC countries were more

interested in obtaining basic assistance at the immediate

patient care level.

A recurrent theme from

most experienced SAARC knee surgeons was a concern regarding low

public health awareness as to the significance of the index ACL

injury and how delayed treatment is associated with injury to

adjacent knee tissues, progressive lower extremity dysfunction,

and decreased general health (India, Nepal, Pakistan). This

finding is similar to rural healthcare issues experienced in

many Western countries where limited medical personnel and

facility resources, increased travel distances, and decreased

public awareness combine to lead patients to only seek

healthcare after their condition or disease has progressed to

being chronic, extremely painful, and highly debilitating.

Optimized use of

available equipment and personnel resources is essential to the

development of improved public health education and awareness

regarding the seriousness of ACL injury. These initiatives may

help to identify currently untapped resources, to better

distribute existing resources, and to facilitate better resource

sharing between SAARC member nations. Cooperative planning in

the prescriptive development of arthroscopy and sports medicine

educational and technology information exchange programs would

help insure that the needs of all SAARC member countries are met

(both basic necessities and technique refinement), better

supporting the organization’s overall vision and mission.

This study is limited in

that it represents only a small sample of experienced SAARC knee

surgeons that specialize in arthroscopic ACL reconstruction.

However, this is a very unique group of experienced knee

surgeons whose ACL reconstruction practice experiences have not

been previously reported. Our literature search did not

identify any previous reports that focused on ACL reconstruction

practices solely in this region of the world. Pilot studies

such as this are important to collect preliminary data, refine

prospective research questions and plans, and develop research

instruments. Based on our study findings, future research

should focus on increasing the awareness of the general public

regarding the potential impact of ACL injury on general health

and quality of life and to increase the awareness of general

practice physicians as to the need to improve examination

documentation and/or to expedite referral to a knee arthroscopy

specialist when indicated. Further study needs to be performed

recruiting a larger number of experienced knee surgeons

including representatives from other SAARC countries such as the

Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Afghanistan.

Given the other

important healthcare problems that exist in the region served by

SAARC14-15 issues related to arthroscopic ACL

reconstruction may not initially seem to be of particular

importance. However, untreated or inappropriately treated lower

extremity musculoskeletal injuries are a serious worldwide

health concern that directly impacts general health status.

Information such as that provided by this study will better

enable the SAARC medical community to establish arthroscopy and

sports medicine education and technology information exchange

program goals in addition to helping design multi-center,

prospective research studies to improve patient healthcare and

quality of life.

Conclusions:

Experienced SAARC knee surgeons displayed similar ACL

reconstruction practices to surgeons from Western countries.

Most of the experienced SAARC knee surgeons that participated in

this study perform < 50 ACL reconstructions per year. There was

trend toward increasing hamstring autograft use and did not

routinely prescribe functional knee braces. Most experienced

SAARC knee surgeons also did not perceive a benefit to changing

their current surgical procedure to an anatomical double bundle

ACL reconstruction technique. Many experienced SAARC knee

surgeons expressed concerns regarding the need for additional

medical and surgical resources, improved arthroscopy and sports

medicine educational and technology information exchange and

fellowship experiences, earlier patient referral with improved

documentation, and improved public awareness regarding the

impact of ACL injury on general health status. Our findings can

assist the SAARC sports medicine community in establishing

realistic organizational goals and in designing prospective

multi-center studies to better serve the needs of all member

nations.

Reference :

1.

South Asian Association

for Regional Cooperation. [http://www.saarc-sec.org/]

Wikipedia. [http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=South

Asian Association for Regional Cooperation&olddid=23181920]

2. Prodromos CC, Han

Y, Rogowski J, Joyce B, Shi K. A meta-analysis of the incidence

of anterior cruciate ligament tears as a function of gender,

sport, and knee injury-reduction regimen. Arthroscopy 2007,

23(12):1320-25.e6

3. [http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/0749-

8063/PIIS074980630700686X.pdf]

4.

Renstrom P, Ljungqvist

A, Arendt E, Beynnon B, Fukubayashi T, et al. Non-contact ACL

injuries in female athletes: An International Olympic Committee

current concepts statement. Br J Sports Med

2008;42(6):394-412. [http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/42/6/394.full.pdf]

5.

Marx RG, Jones EC, Angel

M, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Beliefs and attitudes of members

of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons regarding the

treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthroscopy

2003;19(7):762-70. [http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/0749-8063/PIIS0749806303003980.pdf]

6.

Chaudhary D, Monga P,

Joshi D, Easwaran R, Bhatia N, Singh AK. Arthroscopic

reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using

bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft: Experience of the first

100 cases. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2005;13(2):147-52.

[http://www.josonline.org/pdf/v13i2p147.pdf]

7.

Nag HL, Neogi DS,

Nataraj AR, Kumar VA, Yadav CS, Singh U. Tubercular infection

after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Arthroscopy 2009;25(2):131-6. [http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/0749-8063/PIIS0749806308007263.pdf]

8.

Dhillon MS, Mohan P,

Nagi ON. Does harvesting the medial third of the patellar

tendon cause lateral shift of the patella after ACL

reconstruction? Acta Orthop Belg 2003;69(4):334-40. [http://www.actaorthopaedica.be/acta/download/2003-4/06-dhillon-nagi-.pdf]

9.

Biau DJ, Tournoux C,

Katsahian S, Schranz P, Nizard R. ACL reconstruction: A

meta-analysis of functional scores. Clin Orthop 2007;458:180-7.

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17308473]

10.

West RV, Harner CD.

Graft selection in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J

Am Acad Orthop Surg 2005;13(3):197-207. [http://www.jaaos.org/cgi/content/abstract/13/3/197]

11.

Duquin TR, Wind WM,

Fineberg MS, Smolinski RJ, Buyea CM. Current trends in anterior

cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Knee Surg 2009;22(1):7-12.

[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19216345]

12.

Forssblad M, Valentin A,

Engstrom B, Werner S. ACL reconstruction: Patellar tendon

versus hamstring grafts-economical aspects. Knee Surg Sports

Traumatol Arthrosc 2006;14(6):536-41. [http://www.springerlink.com/content/r146507716477710/]

13.

Wright R, Fetzer GB,

Spindler KP. Bracing after ACL reconstruction: A systematic

review. Clin Orthop 2007:455:162-8. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17279043]

14.

Nishtar S. South Asian

health: What is to be done? SAARC: Regional cooperation for

sustainable health. BMJ2004;328:837-9.[http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/328/7443/837-a?view=long&pmid=15070648]

15.

Khan IM, Khan S, Chotani

R, Laaser U. SARS and SAARC: Lessons for preparedness.

J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad

2003;15(2):1-2. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14552237]

|