|

Abstract:

While pelvic pain in the peripartum period is commonplace,

little is known regarding its relation to symphyseal widening.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate physiologic change in

the widening of the symphysis pubis postpartum, and determine

its relationship to suprapubic pain. Sixty-four women who were

within 48-hours post vaginal delivery were randomly selected. On

postpartum day one or two, participants used a quantitative

scale to assess pubic and back pain. Chart reviews were

conducted to obtain patient, newborn, and labor characteristics.

Ultrasonography was used to measure symphyseal widening.

Outcomes were suprapubic pain correlated to symphyseal widening,

and these two related to other patient, newborn, and labor

characteristics. The results showed that 88% of the women

perceived mild to moderate pubic pain, while 98% had mild to

moderate back pain. Ultrasonagraphy determined that 41 women had

widening greater than 10mm, but mean symphyseal width did not

correlate with back pain (p=0.83), or pubic pain (p=0.87). Pubic

pain increased with increasing patient age (p=0.02). Back pain

increased with precipitous labor, but did not reach significance

(p=0.06). No correlation was found between postpartum pain and

symphyseal widening, suggesting that there are other mechanisms

of peripartum suprapubic pain that must be considered.

J.Orthopaedics 2010;7(1)e8

Keywords:

Pubis symphysis; symphyseal widening; diastasis; postpartum pain

Introduction:

The symphysis pubis is a nonsynovial amphiarthrodial joint that

forms the anterior arch of the pelvis. It is, however, one of

the three pelvic joints that are affected during the peripartum

period due to hormonal influence and mechanical stressors.

The normal physiologic width of the symphysis pubis ranges from

4-6 mm.[1] Relaxation of the symphyseal ligaments during the

peripartum period is a well-described phenomenon, beginning in

the 10th week of gestation and reaching a maximum at or near

term. The average widening during pregnancy ranges from 6 mm to

8 mm, with return to baseline between 4 to 12 weeks

postpartum.[2, 3] It has been hypothesized that relaxin, an

insulin-like hormone, influences cartilage swelling and pelvic

ligament laxity, and thus symphyseal widening; however, most

studies to date have found no association.[4] Post-mortem

studies found that mechanical stressors during labor cause focal

and edematous changes in the ligaments in all women with vaginal

deliveries of a neonate over 2300 grams.[5] Sustained

symphyseal widening greater than 10 mm is considered to be

pathologic, as observations have shown it be associated with

significantly increased maternal morbidity and disability

postpartum.[6]

The incidence of pubic symphysis diastasis is estimated to be 1

in 521 to 1 in 30,000 vaginal deliveries.[7-9] Factors that are

presumed to affect widening include precipitous labor or rapid

descent of the presenting part of the fetus. Other factors, such

as maternal age, parity, pelvimetry or fetal weight have not

been shown to correlate with symphyseal diastasis.[10]

While pelvic pain in the peripartum period is commonplace,

little is known regarding the relationship between symphyseal

widening and the development of this pain. We conducted a pilot

study to evaluate physiologic changes in the widening of the

symphysis pubis postpartum utilizing ultrasonagraphy, and

correlated these findings with patients’ symptoms defined as

suprapubic pain, unrelated to other causes (e.g. uterine

cramps).

Materials

and Methods:

The design of the study involved prospective analysis of

postpartum women in a single urban hospital between October 2006

and May 2007. Patients who were within 48-hours post vaginal

delivery were randomly selected and asked to participate in the

study. Written and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved

consent was obtained from all subjects who met inclusion

criteria and agreed to use of their personal data for research

purposes.

Subjects

Sixty-five women were asked to participate in the

study. Cesarean sections were excluded for this preliminary

study. Sixty-four women (mean age 28.5 years, age range 17-43)

completed the study.

Pain Evaluation

During the patient's initial enrollment on postpartum day

one or two, participants completed a questionnaire using a

quantitative scale to assess pubic and back pain postpartum. The

pain scale quantified pain on a scale from zero to 10, with mild

pain in the 0-3 range, moderate pain in the 4-7 range, and

severe pain in the 8-10 range. A concurrent chart review was

also conducted on all patients to obtain data on patient and

newborn characteristics, as well as on labor. Data obtained from

the questionnaire and chart review were used to evaluate pubic

and back pain in relation to: symphyseal widening and mobility,

parity, length of gestation, age of patient, length of stage two

of labor, mode of delivery, neonate birth weight and height,

degree of perineal tears, blood loss, and type of the female

pelvis (clinically assessed as gynecoid, anthropoid, android, or

pletipoid). In this study, precipitous labor was defined as

labor less than one hour.

Ultrasound Imaging

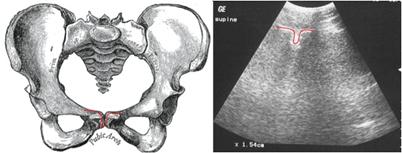

Abdominal ultrasonography was used to measure symphyseal

widening in supine position with the knees and hips extended,

and the knees and hips flexed (Figure 1) on postpartum day one

or two. Images were evaluated by a trained ultrasonographer who

took two separate measurements of symphyseal widening at the

superior aspect of the bony arch in both positions (Figure 2).

The averages of the two measurements in each position were used

for statistical analysis. Measurements of symphyseal mobility

were calculated by subtracting the difference of the average

extended value from the average flexed value.

Figure 1: Ultrasonography was used to measure symphyseal

width in supine position with the knees and hips extended, and

the knees and hips flexed.

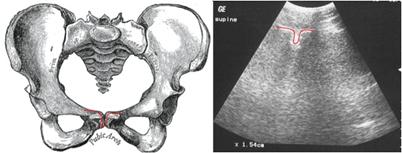

Figure 2:

Ultrasound images (right) were evaluated by a trained

ultrasonographer who took two separate measurements of

symphyseal widening at the superior aspect of the bony arch, as

represented in the schematic drawing of pelvic anatomy (left).

Statistical Analysis

Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the

association between symphyseal width and pubic and back pain, as

well as all three of these and newborn height and weight. In

addition, Spearman’s correlation coefficients were used to

assess the associations between pubic and back pain and maternal

characteristics, such as age, and labor characteristics,

including parity, estimated blood loss, and degree of perineal

tears. Differences in pubic and back pain across ethnicity were

assessed using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA)

tests with Bonferroni-adjusted multiple comparisons. Student’s

t-tests were used for two-way comparisons of pain and symphyseal

widening across newborn gender, induction, and rupture of

membranes.

Results :

There were a total of 64 women, with a mean age of 28.5 years,

and age range from 17 to 43 years. The majority of the patients

were Hispanic (31/64). The women had a mean height of 63 inches,

and a mean weight of 159 pounds. Pregnancy status was para 1 in

26 patients, para 2 in 21 patients, para 3 in 12 patients, and

para 4 in 5 patients. The mean parity for the women studied was

1.95. All patients underwent normal spontaneous vaginal

deliveries (NSVD), with a mean estimated blood loss during labor

of 308 milliliters. Sixteen women had induction with oxytocin.

Thirty-two women had artificial rupture of membranes, whereas 30

had spontaneous rupture of membranes. The mean length of stage

two of labor was 43 minutes. Fifty of the women gave birth in

the Semi-Fowler position, three in the lateral, one in

knee-chest, and 10 in lithotomy. Thirty-nine women sustained a

tear, consisting of 11 vaginal or labial, 13 first-degree

perineal, and 15 second-degree perineal. Thirty-one of the

newborn babies were female, and 33 were male. The mean weight

for the newborns was 3182 grams, and the mean height was 43 cm.

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of these

patients.

The mean symphyseal widening measured was 12 mm, and the mean

change in symphyseal mobility was 5 mm. Sixty-four percent

(41/64) of patients had widening greater than 10 mm. Only one

patient was found to have symphyseal widening greater than 25

mm. This patient, a 29-year old para 5 female who otherwise had

average clinical characteristics, underwent NSVD and perceived

moderate pubic pain and severe back pain. She was the only

subject in our study who perceived severe back pain.

Eighty-eight percent of the women (56/64) perceived mild to

moderate pubic pain, while 98 percent (63/64) had mild to

moderate back pain. Severe pain was a more common complaint

among women with pubic pain (8/64) versus those with back pain

alone (1/64). The mean symphyseal widening did not correlate to

either lower back pain (p=0.83), or pubic pain (p=0.87). Pubic

pain increased with increasing patient age (p=0.02). There was

no significant difference in either pubic or lower back pain

between race groups.

There was no correlation between parity and pain. There was also

no significant relationship between symphyseal widening and

parity. Position and rupture of membranes did not significantly

affect the change in symphyseal widening or increased severity

of pain. Back pain increased with precipitous labor, but did not

reach significance (p=0.06), and pubic pain did not (p=0.72)

either. The size and weight of the newborn was not found to

correlate to either the change in symphyseal width or increased

severity of pain. Two of the deliveries were complicated by

shoulder dystocia, but this was too few to assess for

statistical significance. The measurements of the symphyseal

widening of the two women with this complication were 14 mm and

20 mm.

|

Patient and Newborn Characteristics |

Results |

|

Mean age of Mother (range) |

28.5 years (17-43) |

|

Mean Height of Mother (n=34) |

63 in |

|

Mean Weight of Mother (n=36) |

159 lbs |

|

Race Distribution |

20 Black/31 Hispanic/2 White/11 Other |

|

Mean Length of Gestation |

274.4 days |

|

Mean Parity |

1.95 |

|

Mean symphyseal Width |

12 mm |

|

Mean change in symphyseal width (mobility) |

5 mm |

|

Newborn Gender |

31 Female/33 Male |

|

Mean Newborn Weight |

3182 g |

|

Mean Newborn Height |

43 cm |

|

Mean Length of Stage II of Labor |

43 min |

|

Mean Blood Loss |

308 ml |

Table 1:

Summary of the demographic

and clinical characteristics of subjects.

|

Perceived Pain |

Results |

|

Location |

Mild (%) |

Moderate (%) |

Severe (%) |

|

Pubic symphysis only |

44 (69%) |

12 (19%) |

8 (12%) |

|

Pubic symphysis and back |

9 (14%) |

11 (17%) |

1 (2%) |

|

Back only |

47 (73%) |

16 (25%) |

1 (2%) |

Table 2:

Location of perceived pain is shown according to quantitative

rating by subjects during encounters.

Discussion :

In this study we found the majority of postpartum women to have

experienced a “pathologic” symphyseal separation. We found no

correlation, however, between perceived postpartum pain and

symphyseal widening. In pregnancy, pelvic ligament relaxation

and increased joint mobility is observed.[11] Peripartum pubic

and lower back pain is experienced in approximately 50 percent

of women during pregnancy, and there is some evidence that pain

is associated with symphyseal widening during pregnancy.[12-15]

However, the correlation

between antepartum symphyseal widening and pain is debatable, as

Bjorklund et al (2000) found that while widening was strongly

associated with pain, there was no evidence that the degree of

symphyseal widening determined the severity of pubic pain in

pregnancy or postpartum. This finding suggests that there are

other mechanisms of peripartum pain that must be considered.[12]

The literature suggests that symphyseal widening during

pregnancy is due to both hormonal influence and mechanical

stressors. It is possible that postpartum pain is a continuum of

antepartum pain and mediated by these same factors; however, the

variability of postpartum pain in location and severity suggests

that there may be two distinct etiologies. The etiology of mild

to moderate postpartum pain that ceases within days after

delivery may be explained by the relaxation of the symphysis

pubis during delivery. This physiologic widening is consistent

with our study finding of 88 percent of women who perceived mild

to moderate pubic pain (Table 2). A retrospective study that

examined women with symptomatic symphyseal separation found that

55 percent of women described pubic pain as their only symptom,

and only two women did not suffer from pain in this area.[16] A

meta-analysis of case reports found that the predominating

symptom of separation of the symphysis pubis is a constant, dull

pain located directly over the symphysis.[9]

According to Larsen et al (1999), approximately four percent of

women experience severe pain localized to the pubis and low back

for several months postpartum.[17] Though not all of these

women sustained a symphyseal diastasis, the etiology of this

more intense and prolonged pain is believed to be due to pelvic

ring instability at both the pubic symphysis, and if severe

enough, also at the sacroiliac joints.[11] Studies have reported

that symphyseal diastasis exceeding 40 mm disrupts the

sacroiliac ligaments.[18, 19] This suggests that patients who

experience mild to moderate postpartum pain suffer from

physiologic pelvic dysfunction, while those with severe pain

likely suffer symphyseal diastasis due to biomechanical

disruption of the muscles and ligaments within the pelvic ring

during delivery.[11, 20, 21] In this study, we

define symphyseal diastasis as disruption of the pelvic ring

with more than 25 mm of symphysis pubis separation.[22]

Due to similarity in presentation and symptoms, and a lack of

objective measures of ligament relaxation or pelvic instability,

there is confusion in both the terminology and criteria used to

describe and diagnose symphysis pubis dysfunction, symphysis

pubis diastasis, and peripartum back and pubic pain.[11, 20, 23]

As a result,

the diagnosis is often

based on the patient’s information about

severity and location of

pain.

In this study, we considered pubic and lower back pain as

separate entities with similar etiologies along a spectrum of

pelvic ligament laxity. Though we did not find any significant

difference in the frequency or severity of pubic pain versus

back pain in the postpartum period, it is hypothesized that

pubic pain would not only be a more common complaint, but also

less pronounced than back pain due to the more extreme etiology

of the latter.

The literature is inconclusive on the relationship between a

precipitous second stage of labor and postpartum pain.[24]

While some have found no correlation, a series of case

reports suggest that rupture of the symphysis pubis in

spontaneous labor is due to marked rapidity of labor.[9] In our

study we found a trend of low back pain increasing with

precipitous labor, though it was not statistically significant.

A plausible explanation for this observation is that the

ligaments may undergo plastic rather than elastic deformation,

which may contribute to a higher rate of dysfunction or

diastasis, not only at the symphysis pubis, but also at the

sacroiliac joint.

The literature is inconsistent with regards to peripartum pain

and age of the mother. Some authors found that younger women

were more likely to have pain postpartum, while others reported

no effect.[14] Our findings suggest that pain increased with

maternal age. One author with similar findings suggested that

this result may be related to the women in their population

having a higher age at their first pregnancy.[25]

Another similar observation was reported for back pain

experienced during pregnancy, but the author was unable to

separate the effects of age on pain from those of parity.[26]

We found that parity was not

correlated to back pain or pelvic pain, but did not examine

whether there were any confounding effects caused by maternal

age. Wu et al suggest that the real pattern of association

between pain is a “U” shape – there is high risk for very young

women whose bodies are not yet ready for pregnancy, then risk

decreases until women get much older, or undergo more

pregnancies.[23] The literature is not conclusive as to whether

postpartum pain increases with the number of pregnancies;

however, it has been shown that pain in the back and pubis after

previous pregnancies increases the risk for peripartum pain in

subsequent pregnancies.[27] It is likely that pain

may be due to the aging process and ligamentous laxity

associated with increasing age, rather than parity.[28]

It has been suggested that postpartum pain may occur as a result

of traumatic delivery, such as in shoulder dystocia.[11]

There is some evidence that shoulder dystocia is associated with

symphyseal separation. In the only case of its type to be

reported, shoulder dystocia was resolved through spontaneous

separation of the pubis symphysis.[29] Other reports have found

separation of the pubis symphysis following the McRobert’s

maneuver.[30, 31] In our study, we had two patients with

complications of shoulder dystocia during delivery, both of

which had widening greater than 1 cm. A larger sample size would

enable us to consider the relationship between the McRobert’s

maneuver, symphyseal widening, and related pain.

Ultrasound is a consistent, cost-effective and harmless means of

measurement. Although discrepancies exist regarding ultrasound

technology for measurement of symphyseal widening, we considered

the upper margin of the symphysis pubis joint with the patient

supine as the true symphyseal width. The measurements in this

study are consistent with other authors who have found

ultrasonography to be a reliable and reproducible method to

measure symphyseal width.[27].

The limitation of this study is its small sample size. A post

hoc power analysis was performed. This showed that if we

increased the number of patients 50-fold (3,064) we would

increase our power to 80 percent. In addition, the relationship

between parity and pain in relation to maternal age may be

further elucidated by gaining a greater sample of women.

Pain is subjective and patient-to-patient variations may have a

psychological component as well as a physical component which

was not measured.

Future directions of this study include consideration of

antepartum pain to determine whether postpartum pain is residual

antepartum pain or due to dysfunction and rupture of ligaments.

Postpartum pubic pain and back pain are similar in etiology, yet

unique in frequency, location, and severity. The diagnosis is

most commonly made based on clinical presentation, although the

literature on ultrasonography to aid in the diagnosis continues

to grow.

In conclusion, we believe that although a diagnosis of

symphyseal dysfunction or diastasis does not change the

management during labor, a better understanding of the etiology

of postpartum pain will help in the management of patients with

this condition as well as potentially aid patients who sustain

this condition with subsequent pregnancies.

Reference :

-

Wurdinger, S., et al., MRI of the pelvic ring joints

postpartum: normal and pathological findings. J Magn Reson

Imaging, 2002. 15(3): p. 324-9.

-

Heyman, J., Lundquist A., The symphysis pubis in pregnancy

and parturition. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 1932. 12: p.

35.

-

Alicioglu, B., et al., Symphysis pubis distance in adults:

a retrospective computed tomography study. Surg Radiol

Anat, 2008. 30(2): p. 153-7.

-

Dietrichs, E. and O. Kogstad, "Pelvic girdle

relaxation"--suggested new nomenclature. Scand J Rheumatol

Suppl, 1991. 88: p. 3.

-

Scriven, M.W., D.A. Jones, and L. McKnight, The importance

of pubic pain following childbirth: a clinical and

ultrasonographic study of diastasis of the pubic symphysis.

J R Soc Med, 1995. 88(1): p. 28-30.

-

Lindsey, R.W., et al., Separation of the symphysis pubis in

association with childbearing. A case report. J Bone Joint

Surg Am, 1988. 70(2): p. 289-92.

-

Heckman, J.D. and R. Sassard, Musculoskeletal

considerations in pregnancy. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1994.

76(11): p. 1720-30.

-

Luger, E.J., R. Arbel, and S. Dekel, Traumatic separation

of the symphysis pubis during pregnancy: a case report. J

Trauma, 1995. 38(2): p. 255-6.

-

Reis RA, B.J., Arens RA et al., Traumatic separation of the

symphysis pubis during spontaneous labor: With a clinical and

X-ray study of the normal symphysis pubis during pregnancy and

the puerperium. . Surg Gynecol Obstet, 1932. 55: p. 18.

-

Snow, R.E. and A.G. Neubert, Peripartum pubic symphysis

separation: a case series and review of the literature.

Obstet Gynecol Surv, 1997. 52(7): p. 438-43.

-

Leadbetter, R.E., D. Mawer, and S.W. Lindow, Symphysis

pubis dysfunction: a review of the literature. J Matern

Fetal Neonatal Med, 2004. 16(6): p. 349-54.

-

Bjorklund, K., et al., Symphyseal distention in relation to

serum relaxin levels and pelvic pain in pregnancy. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2000. 79(4): p. 269-75.

-

Fast, A., et al., Low-back pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila

Pa 1976), 1987. 12(4): p. 368-71.

-

Ostgaard, H.C. and G.B. Andersson, Postpartum low-back

pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1992. 17(1): p. 53-5.

-

Ostgaard, H.C., G.B. Andersson, and K. Karlsson, Prevalence

of back pain in pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1991.

16(5): p. 549-52.

-

Owens, K., A. Pearson, and G. Mason, Symphysis pubis

dysfunction--a cause of significant obstetric morbidity.

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2002. 105(2): p. 143-6.

-

Larsen, E.C., et al., Symptom-giving pelvic girdle

relaxation in pregnancy. I: Prevalence and risk factors.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 1999. 78(2): p. 105-10.

-

Callahan, J.T., Separation of the symphysis pubis. Am J

Obstet Gynecol, 1953. 66(2): p. 281-93.

-

Hagen, R., Pelvic girdle relaxation from an orthopaedic

point of view. Acta Orthop Scand, 1974. 45(4): p. 550-63.

-

Hansen, A., et al., Postpartum pelvic pain--the "pelvic

joint syndrome": a follow-up study with special reference to

diagnostic methods. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2005.

84(2): p. 170-6.

-

Owens K., P.A., Mason G., Pubic Symphysis Separation.

Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review, 2002. 13: p. 13.

-

Kellman, J.F., Browner B.D., ed. In Skeletal Trauma.

Fractures, Dislocations, and Ligamentous Injuries.

Fractures of the Pelvic Ring, ed. J.J.B. Browner B.D., Levine

A, Trafton PG. Vol. 1. 1992, W.B. Saunders: Philidelphia. pp.

859-863.

-

Wu, W.H., et al., Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain

(PPP), I: Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence.

Eur Spine J, 2004. 13(7): p. 575-89.

-

Breen, T.W., et al., Factors associated with back pain

after childbirth. Anesthesiology, 1994. 81(1): p. 29-34.

-

Mens, J.M., et al., Understanding peripartum pelvic pain.

Implications of a patient survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976),

1996. 21(11): p. 1363-9; discussion 1369-70.

-

Mantle, M.J., R.M. Greenwood, and H.L. Currey, Backache in

pregnancy. Rheumatol Rehabil, 1977. 16(2): p. 95-101.

-

Bjorklund, K., M.L. Nordstrom, and S. Bergstrom,

Sonographic assessment of symphyseal joint distention during

pregnancy and post partum with special reference to pelvic

pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 1999. 78(2): p. 125-30.

-

Conn, M., ed. Handbook of Models for Human Aging. A

Model for Understanding the Pathomechanics of Osteoarthritis

in Aging, ed. M.A. Andriacchi TP. 2006, Elsevier: Amsterdam.

pp. 351-366.

-

Niederhauser, A., et al., Resolution of infant shoulder

dystocia with maternal spontaneous symphyseal separation: a

case report. J Reprod Med, 2008. 53(1): p. 62-4.

-

Culligan, P., S. Hill, and M. Heit, Rupture of the

symphysis pubis during vaginal delivery followed by two

subsequent uneventful pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol, 2002.

100(5 Pt 2): p. 1114-7.

-

Heath, T. and R.B. Gherman, Symphyseal separation,

sacroiliac joint dislocation and transient lateral femoral

cutaneous neuropathy associated with McRoberts' maneuver. A

case report. J Reprod Med, 1999. 44(10): p. 902-4.

|