|

Abstract:

Fibroblast

growth factor 23 (FGF23), a protein capable of inhibiting renal

tubular epithelial phosphate transport, is thought to be the

underlying mechanism in tumor-induced- osteomalacia. In this

report, we present a case of tumor-induced- osteomalacia

associated with an oral soft tissue tumor that caused

overexpression of FGF23.

A 35-year-old man suffered from bone pain for 2 years and he

presented the difficulty in walking due to severe bone pain and

muscle weakness in his lower limbs. Radiography identified old

fractures and severe bone atrophy at multiple bones and bone

scintigraphy revealed abnormal tracer uptake. Laboratory

findings showed that the serum phosphate level was very low (0.8

mg/dl), and FGF23 serum level was elevated (128.7 pg/ml). We

diagnosed the patient as FGF 23-producing tumor-induced

hypophosphatemic osteomalacia a. About 2 years after the start

of our follow-up, a small soft tumor was found behind of the

lower lip. After resection of the tumor, the serum phosphate and

FGF23 levels rapidly normalized and the severe bone pain

markedly improved. Furthermore, the tissue was stained positive

using anti-human FGF23 antibody. In this report, we presented

the rare case that FGF 23–producing tumor within the oral cavity

inducing osteomalacia with severe clinical symptom including

bone pain, multiple fragility fractures, muscle weakness and

gait disturbance.

J.Orthopaedics 2009;6(4)e11

Keywords:

fibroblast

growth factor (FGF 23); tumor-induced osteomalacia; oral soft

tumor; bone pain; phosphate

Introduction:

Osteomalacia is a metabolic bone disorder resulting from

inadequate mineralization of osteoid in mature bone. One of the

most unusual types of osteomalacia is tumor-induced osteomalacia,

which is characterized clinically by bone pain, fractures,

muscle weakness, gait disturbance, renal phosphate wasting,

hypophosphatemia, decreased serum 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D

levels, and resistance to vitamin D supplementation (1). Recent

reports have indicated that fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23)

is a protein capable of inhibiting renal tubular epithelial

phosphate transport (2), which is thought to be the underlying

mechanism in tumor-induced- osteomalacia2. FGF23 has been

identified as a member of the FGF family and shown to have an

important role in phosphate homeostasis (3) Most of the tumors

causing osteomalacia are benign and occur in the lower and upper

extremities; however, the tumors are frequently very small,

making discovery difficult (4, 5).

In this report, we present a case of tumor-induced- osteomalacia

associated with an oral soft tissue tumor that caused

overexpression of FGF 23, and the rapid normalization of FGF23

levels following removal of the tumor. Subsequently, the

normalization of biochemical parameters of mineral metabolism

correlated with the improvement in severe bone pain and

activities of daily living (ADL).

Case Report:

A

35-year-old man had experienced bone pain in ribs and right hip

for 2 years. At 6 months after the onset of pain, he underwent a

medical examination to establish the cause of the bone pain in

another hospital. However, the origin of the symptoms could not

be found, and the patient was followed up with non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drug treatment for over 1.5 years. The

symptoms gradually worsened and he presented the difficulty in

walking due to severe bone pain and muscle weakness in his lower

limbs. The patient was referred to our hospital for further

examination because of the unknown origin of the symptoms.

The patient

complained of a severe diffuse bone pain all over his body. He

was wheelchair bound due to significant pain in hips and knees

with a visual analogue scale (VAS) of 8.4, and muscle weakness

of lower limbs. He did not have a significant family history of

bone diseases or any history of other diseases. Previously he

had been healthy and worked as a truck driver with a high level

of physical activity. His height, weight, and body mass index

was 159.1 cm, 52.6 kg, and 20.8 kg/m2, respectively.

The muscle strength of the lower limbs was found to be grade 3

on the basis of manual muscle testing. We found no other

abnormalities on physical examination. Radiography identified

multiple old fractures and severe bone atrophy at spine, ribs,

pubis, ischium and lower limbs (data not shown). Bone mineral

density (BMD) was markedly decreased at the lumbar spine (L2-L4;

0.512 g/cm2, T score -3.8) and femoral neck (0.478

g/cm2, T-score -3.6) (QDR4500; Hologic, Waltham, MA,

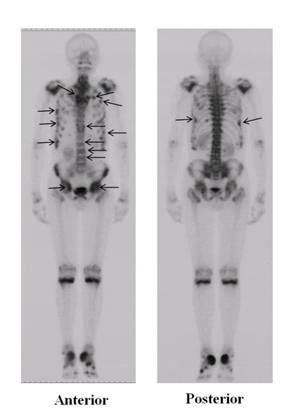

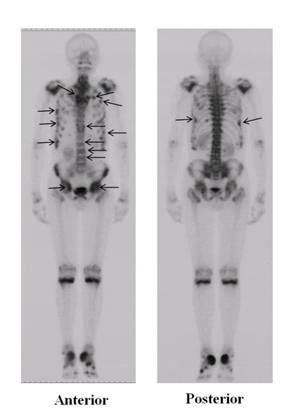

USA). Bone scintigraphy with 99mTc-methylene

diphosphonate revealed abnormal tracer uptake in multiple bones

including the spine, ribs, pelvis and femurs, suggesting

clinical fractures (Fig. 1). Laboratory findings showed that the

serum phosphate (IP, reference range 2.5-4.5 mg/dl) level was

very low (0.8 mg/dl), and serum total alkaline phosphatase (ALP,

reference range 110-370 IU/l) and bone specific alkaline

phosphatase (BAP, reference range 13-33.9 U/l) levels were

markedly increased at 1878 IU/l and 312 U/l, respectively. The

urinary N-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (uNTX,

reference range, < 66.2 nmol

bone collagen equivalent / mmol·creatinine

[nMBCE/mM·Cr]) level was 43.7

nMBCE/mM·Cr, and the circulating 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D,

reference range, 20-60) level was very low (8 pg/ml) despite the

hypophosphatemia. Several serum tumor markers, such as CEA, AFP,

CA19-9 and PSA, were within reference ranges. Other laboratory

data were also within reference ranges. Thus, we diagnosed the

patient as hypophosphatemic osteomalacia, which was confirmed by

an iliac bone biopsy. Furthermore, considering that he had been

healthy for 33 years prior to the onset of his disease and that

the symptoms had worsened during the 2-year- follow-up,

tumor-induced- osteomalacia was considered to be the most

probable cause of this patient.

However, no

significant abnormalities apart from skeletal organs were

identified using computed tomography, ultrasonography, 201Tl

scintigraphy, and endoscopy for the digestive organs.

Furthermore, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan failed to

reveal any abnormalities in any part of the body. On the basis

of a recent report that venous sampling for FGF23 confirms

preoperative diagnosis of tumor-induced- osteomalacia (6), we

measured FGF23 concentration by ELISA (Kainos, Japan) in

subcutaneous venous samples (reference range, 10-50 pg/ml) taken

from 6 points in the upper and lower extremities. The FGF23

serum level was elevated in samples from all 6 points, including

the bilateral hands (right 181.4, left, 195.5 pg/ml), femurs

(right 181.4, left 222.3 pg/ml) and lower legs (right 189.1,

left 183.6 pg/ml); however, there were no differences among

samples. From these results, we diagnosed the patient as FGF

23-producing tumor-induced hypophosphatemic osteomalacia

although no causative tumor was identified. Treatment with

alfacalcidol (3.0 µg / day) and sodium acid phosphate (500mg of

elemental phosphorus three times daily) was initiated on the

basis of the diagnosis. Subsequently, his pain slightly

improved, but the patient still suffered from multiple bone pain

and presented with the difficulty in walking without aid.

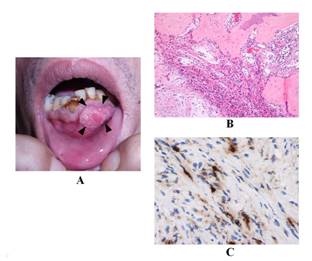

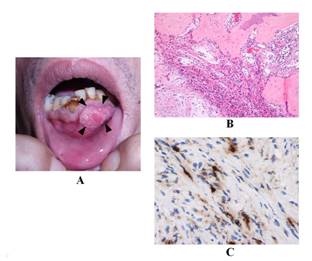

About 2

years after the start of our follow-up, the patient became aware

of a small soft tumor behind of the lower lip. Six months later,

the tumor size gradually increased until it was 23mm × 14mm ×

10mm in size (Fig. 2A) so that the patient underwent resection

of the tumor. The pathologic diagnosis of the tumor was

consistent with fibroma, and revealed a fibroblastic

proliferation with fibrous connective tissues and reactive bone

formation without any evidence of malignancy (Fig. 2B).

Furthermore, the tissue was stained positive using polyclonal

rabbit anti-human FGF23 antibody (FGF23 (FL251)) (1:500

dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) (Fig 2C).

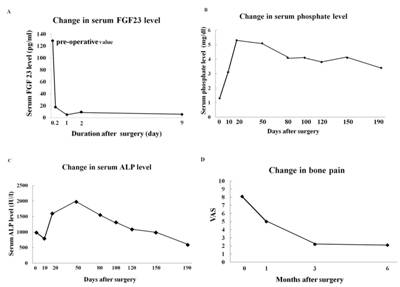

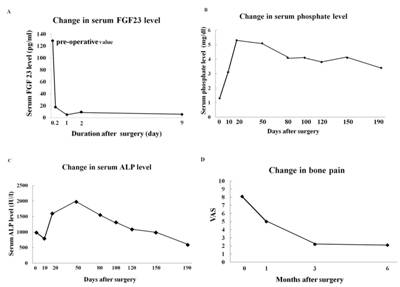

At 5 hours

post-surgery, the serum FGF 23 level rapidly decreased to a

reference range, and thereafter remained under 10 pg/ml (Fig.

3A). The serum phosphate level rapidly increased and remained

within the reference range for more than 9 months post-surgery

(fig. 3B). ALP initially rose following tumor removal and then

gradually declined. Normalization of the ALP was not achieved

until 6 months post-surgery (Fig. 3C). The severe bone pain of

the patient gradually decreased although moderate pain remained

post-operatively (Fig. 3D). At 6 months post-operatively, the

patient was able to walk without any supports and had resumed

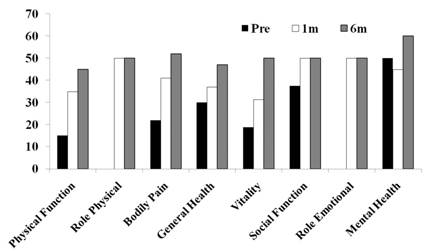

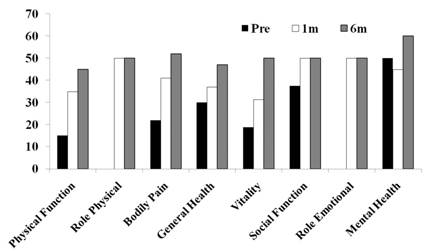

low-level physical activity. General health was assessed with

use of the Short Form-36 (SF-36) (7, 8) and post-operative SF-36

scores were improved compared with pre-operative scores (Fig.

4).

Figure 1

Bone scintigraphy of the patient

Bone

scintigraphy with 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate

revealed abnormal tracer uptake in multiple bones including the

spine, ribs, pelvis and femurs (arrows).

Figure 2

FGF23 producing tumor within the oral cavity

The soft

tumor was located behind the lower lip (tumor size was 23mm ×

14mm × 10mm) (A, arrow heads). Pathologic diagnosis of the tumor

was consistent with fibroma, and revealed a fibroblastic

proliferation with fibrous connective tissues and reactive bone

formation without evidence of malignancy (B, Hematoxilin-Eosin

stain). The tissue was stained positive using polyclonal rabbit

anti-human FGF23 antibody (C, single immunolabeling (peroxidase

and DAB).

Figure 3

At 5 hours

post-surgery, the serum level of FGF23 rapidly decreased from

128.7 pg/ml to 17.6 pg/ml, and thereafter remained under 10

pg/ml (A). The serum phosphate level rapidly increased to 3.1

mg/dl and remained within the reference range (2.5 – 4.5 mg/dl)

for more than 9 months post-surgery (B). ALP initially rose

following the tumor removal and then gradually declined.

Normalization of the ALP (110 – 370) was not achieved until 6

months post-surgery (ALP, 585 IU/l) (C). The severe bone pain

(VAS 8.1) gradually decreased, although moderate pain (VAS 2.1)

remained postoperatively (D).

Figure

4

Pre- and 1-

and 6-month post-operative SF-36 scores

The

scores for the eight subscales of the SF-36 (Physical Function,

Role Physical, Bodily pain, General Health, Vitality, Social

Function, Role Emotion and Mental Health) were measured prior to

the surgery (black bars) and at 1 month (white bars) and 6

months (striped bars) post-surgery

Discussion :

Tumor-induced osteomalacia is an acquired, paraneoplastic

syndrome that is characterized by hypophosphatemia due to renal

phosphate wasting, osteomalacia, bone pain, proximal muscle

weakness, fractures and functional disability (1). The disease

shares similar of clinical symptoms with X-linked

hypophosphatemia (XLH), autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic

rickets (ADHR), and autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets

(ARHR) (9-12). In this case, the patient had no family history

so that we preoperatively suspected tumor-induced- osteomalacia

rather than genetic diseases such as XLH, ADHR and ARHR.

Interestingly, the site of the tumor was within the oral cavity

despite the fact that most tumors responsible for tumor-induced-

osteomalacia is localized in the lower and upper limbs. To the

best of our knowledge, there have been few previous reports of

FGF 23–producing tumors within the oral cavity inducing

osteomalacia (1, 4, 5).FGF 23 was recently identified as a

causative humoral factor for tumor-induced- osteomalacia, and is

known to reduce serum phosphate level by inhibiting proximal

tubular phosphate reabsorption and decreasing serum 1,25(OH)2D

levels (2, 13). Endo et al. (14) proposed a set of diagnostic

criteria based on the serum phosphate and FGF 23 levels as

follows; in adults, a serum phosphate level of less than 2.5

mg/dl and a FGF 23 level of more than 30 pg/ml by intact FGF 23

assay indicate the presence of diseases caused by excess FGF 23,

such as tumor-induced- osteomalacia and XLH. In our case, the

data from the patient met these criteria, with the serum FGF23

level, in particular, greater than 180 pg/ml.

Measurement

of serum FGF 23 level in samples obtained from peripheral veins

is useful for the diagnosis and post-operative monitoring of

patients with tumor-induced- osteomalacia (6). However, we could

not locate the responsible tumor in the oral cavity because the

FGF23 levels were elevated in the samples from both the upper

and lower limbs, and the patient rejected further invasive

examination, such as sample collection from all major veins

through a catheter inserted through the femoral vein (6).

Because the tumor was found in the oral cavity, it is reasonable

that FGF23 levels from extremities showed no difference. It is

possible that FGF23 was higher if FGF23 levels in jugular veins

could be measured.

Various

types of mesenchymal tumors associated with tumor-induced-

osteomalacia have been reported, including hemangiopericytoma,

hemangioma, giant cell tumor and osteoblastoma (4, 5). Weidner

and Santa Cruz (4) coined the term “phosphaturic mesenchymal

tumor, mixed connective tissue variant” (PMTMCT) to describe

these unique lesions, characterized by a distinctive admixture

of spindled cells, osteoclast-like giant cells, microcysts,

prominent blood vessels, cartilage-like matrix, and metaplastic

bone. Although the pathologic diagnosis in our case was fibroma,

the histological features could be included into a spectrum of

PMTMCT described as the most frequent histology associated with

tumor-induced- osteomalacia (4, 5).

In this

report, we described a severe case of tumor-induced-

osteomalacia associated with a histologically diagnosed fibroma

that secreted high levels of FGF23. In most orthopaedic clinics,

it is sometimes difficult to distinguish severe osteomalacia

from osteoporosis as the clinical symptoms of both, including

low BMD, bone pain and multiple fragility fractures are similar.

In fact, this case was also diagnosed as a severe osteoporosis

before consultation at our hospital. We believe that it is

important to consider osteomalacia associated with FGF

23-producing- tumor in the differential diagnosis of patients

presenting with the sudden onset of low BMD, bone pain,

fragility fractures and hypophosphatemia. The informed consent

for the publication of data from the case was received from the

patient and the family.

Reference :

-

Schapira

D, Ben Izhak O, Nachtigal A, Burstein A, Shalom RB, Shagrawi

I, et al. Tumor-induced osteomalacia. Seminars in Arthritis

Rheumatism 1995; 25:35-46.

-

Shimada

T, Mizutani S, Muto T, Yoneya T, Hino R, Takeda S, et al.

Cloning and characterization of FGF23 as a causative factor of

tumor-induced osteomalacia. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences 2001; 98:6500-6505.

-

Fukumoto

S, Yamashita T. FGF23 is a hormone-regulating phosphate

metabolism-Unique biological characteristics of FGF23. Bone

2007; 40:1190-1195.

-

Weidner

N, Santa Cruz D. Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors: a

polymorphous group causing osteomalacia or rickets. Cancer

1987; 59:1442-1454.

-

Folpe AL,

Fanburg-Smith JC, Billings SD, Bisceglia M, Bertoni F, Cho JY,

et al. Most osteomalacia-associated mesenchymal tumors are a

single histopathologic entity: an analysis of 32 cases and a

comprehensive review of the literature. American Journal of

Surgical Pathology 2004; 28: 1-30.

-

Takeuchi Y, Suzuki H,

Ogura S, Imai R, Yamazaki Y, Yamashita T, et al. Venous

Sampling for fibroblast growth factor-23 confirms preoperative

diagnosis of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Journal of Clinical

Endocrinology and Metabolism 2004; 89: 3979-3982.

-

Fukuhara S, Bito S,

Green J, Hsiao A, Kurokawa K. Translation, adaptation, and

validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Japan.

Journal Clinical Epidmiology 1998; 51: 1037-1044.

-

Fukuhara S, Ware JE,

Kosinski M, Wada S, Gandek B. Psychometric and clinical tests

of validity of the Japanese SF-36 Health Survey. Journal

Clinical Epidmiology 1998; 51: 1045-1053.

-

ADHR

Consortium. Autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets is

associated with mutations in FGF23. Nature Genetics

2000; 26:345-348.

-

Hyp-Consortium. A

gene (PEX) with homologies to endopeptidases is mutated in

patients with X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets. Nature

Genetics 1995; 11: 130-136.

-

Lorenz-Depiereux

B, Bastepe M, Benet-Pagčs A, Amyere M, Wagenstaller J,

Müller-Barth U, et al. DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive

hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the

regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nature Genetics

2006; 38: 1248-1250.

-

Feng JQ,

Ward LM, Liu S, Lu Y, Xie Y, Yuan B, et al. Loss of DMP1

causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for

osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nature Genetics 2006;

38: 1310-1315.

-

Shimada

T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, Muto T, Hino R, Takeuchi Y, et al.

FGF-23 is a potent regulator of Vitamin D metabolism and

phosphate homeostasis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research

2004; 19:429-435.

-

Endo I,

Fukumoto S, Ozono K, Namba N, Tanaka H, Inoue D, et al.

Clinical usefulness of measurement of fibroblast growth factor

23 (FGF23) in hypophosphatemic patients: Proposal of

diagnostic criteria using FGF23 measurement. Bone 2008; 42:1235-1239.

|