|

Abstract:

Patients

with metastatic carcinoma commonly have multiple lytic bone

lesions. We

present a patient with multiple bone lytic lesions who by

clinical, radiologic and morphologic evidence appeared to have

metastatic carcinoma.

MRI revealed lesions in the right ilium, right sacroiliac

joint, right proximal femur, left ilium and left side of the

sacrum. Both

CT and MRI did not disclose any soft tissue mass or

lymphadenopathy. A

biopsy of the left posterior iliac crest showed a high grade

undifferentiated neoplasm with a marked desmoplastic response.

Only after exclusion of non-hematopoietic neoplasms by an

extended immunohistochemical panel was the diagnosis of primary

bone lymphoma (PBL, centroblastic variant) made.

This report illustrates the necessity of radiologic and

morphologic correlation in establishing the correct diagnosis.

PBL can infrequently involve multiple bones of the pelvis

in the absence of a soft tissue mass or regional lymphadenopathy

with an associated carcinoma-like desmoplastic response.

J.Orthopaedics 2009;6(2)e7

Keywords:

lymphoma;

bone; metastatic; carcinoma

Introduction:

PBL is an

infrequent bone lesion, representing only 5% of all bone

neoplasms.1 Patients typically complain of

localized pain and/or a palpable mass. PBL is defined as a

lymphoma involving a single skeletal site with or without

involvement of regional lymph nodes.2 Less

commonly, PBL involves multiple bones with an associated soft

tissue mass. Long bones are most frequently involved,

primarily at the diametaphysis. Thus clinical and

radiologic criteria may be used to suggest PBL in the

differential diagnosis. The presence of multiple lytic

bone lesions, especially in flat bones such as the pelvis, in

the absence of an associated soft tissue mass and with no

regional lymphadenopathy is more frequently associated with

metastatic carcinoma.3 We report a patient with

the later presentation who after careful pathologic and

radiologic correlation was diagnosed with a PBL. This

report demonstrates the importance of clinicopathologic

evaluation as well as a systematic immunohistochemical approach

to the diagnosis of PBL. Furthermore, PBL may be

associated with a striking carcinoma-like desmoplastic reaction.

Case

Report:

A

53 year old woman complained of generalized abdominal pain as

well as back pain. Physical

exam did not reveal any specific findings.

A CT

scan disclosed a lytic lesion involving the left portion of the

sacrum adjacent to the inferior portion of the left sacroiliac

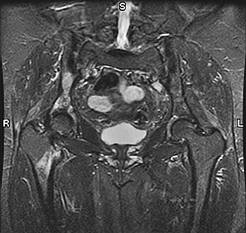

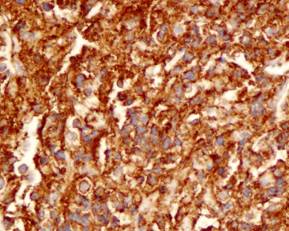

joint. An MRI

revealed lytic lesions in the right ilium, the right sacroiliac

joint, right proximal femur, left ilium and left side of the

sacrum near the left sacroiliac joint (Figure 1).

No soft tissue mass or lymphadenopathy was seen.

The radiologic impression was that of metastatic disease.

Figure

1: MRI of the pelvis and femoral heads showing multiple lesions

in the right inferior pelvis, right proximal femoral head, left

ilium and left sacrum.

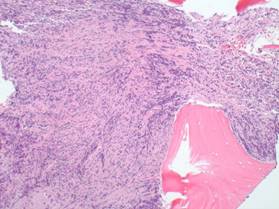

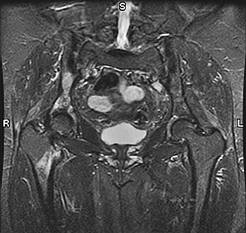

A

bone biopsy of the left posterior iliac crest was performed.

Approximately 20-30% of the bone biopsy showed a high grade

malignancy with associated fibrous tissue and bone sclerosis

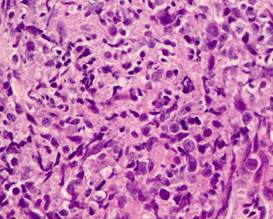

(Figure 2).

Figure

2: Infiltrative malignant cell population with fibrosis and bone

sclerosis, suggestive of metastatic carcinoma

(hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification X10).

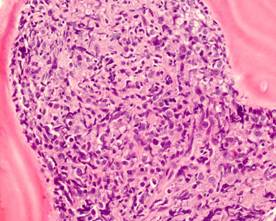

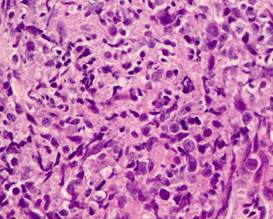

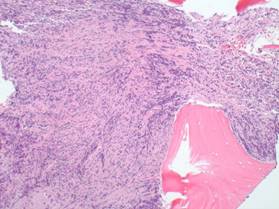

The

cells revealed large nuclei with vesicular chromatin and

non-prominent nucleoli infiltrating in a non-cohesive pattern

(Figure 3, 4).

Figure

3: Large, malignant non-cohesive cells with associated fibrosis

(hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification X20).

Figure

4: Malignant cells with large nuclei and vesicular chromatin

pattern (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification X40).

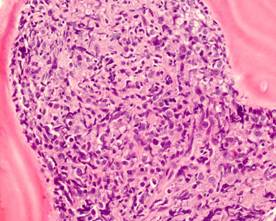

In

addition there were areas of osteoclastic and osteoblastic

activity with prominent woven bone formation and sclerosis.

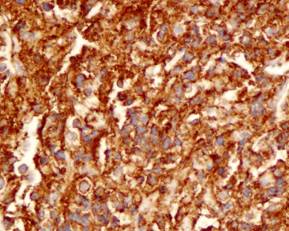

Immunohistochemistry showed the atypical population was positive

for CD45, CD20, and CD79a (Figure 5). They were focally

positive for BCL-6 and CD10. These cells were negative for

CK7, CK20, Cam5.2, Mak6, CK AE1/AE3, EMA, TTF-1, MART-1, HMB-45,

EMA, CD3 and CD138. Based on the immunohistochemical

findings, the diagnosis of large B cell lymphoma, centroblastic

variant was made. Of note, the bone marrow aspirate did not

reveal any malignant cells.

Figure

5: The malignant cells reveal CD20 positive immunostaining

(original magnification X40).

Discussion :

Metastatic

neoplasms are the most frequent of all malignancies of bone.3

In most cases the diagnosis is readily made since the

lesions are numerous and the presence of the primary malignancy

is known or evident. The

great majority of bone metastases originate in breast, lung,

prostate, thyroid or kidney.4

Approximately 70% of bone metastases affect the axial

skeleton (skull, ribs, spine, sacrum). The remaining metastatic

lesions involve large bones of the limbs alone or in combination

with the axial skeleton.

Radiologically,

the lesions are usually osteolytic, but may be osteoblastic or

both.5, 7 Periosteal bone proliferation and exuberant

new bone formation can less commonly occur.

In the absence of a known primary, histological

evaluation combined with a selective immunohistochemical panel

can narrow or confirm the nature of the neoplasm. Associated

histologic findings such as a marked desmoplastic response may

be also be helpful in identifying the presence of carcinoma.6

In

contrast to metastatic bone neoplasms, PBL is infrequent.

Although PBL usually affects the diaphysis or metaphysis

of a long bone, it can more rarely involve multiple bones, thus

simulating metastases.7

The absence of an associated soft tissue mass or

lymphadenopathy does not exclude the presence of PBL.

The diagnosis of PBL clearly requires histologic as well

as immunohistochemical analysis.

Usually the H and E stained tissue suggests a lymphoma as

opposed to a carcinoma, even in those cases where the clinical

and radiological findings are more suggestive of bone

metastases.

Our

patient revealed considerable clinical and radiological overlap

with bone metastases. PBL was not clinically suspected due to

the multifocal lytic lesions of the pelvis and the right

proximal femur. Furthermore, the absence of a soft tissue mass,

lymphadenopathy or “B” symptoms did not raise the

possibility of PBL to the clinicians or radiologists.

The presence of a high grade malignant cell infiltrate

associated with marked fibrosis and new bone formation continued

to suggest the diagnosis of bone metastasis even after reviewing

the H and E slides of the biopsy.

In fact, carcinoma frequently evokes a desmoplastic

response with new and sclerotic bone formation.

PBL usually infiltrates in an interstitial pattern with

at most associated increased reticulin fibers surrounding

individual or clusters of malignant cells.2

The

establishment of the correct diagnosis in this unusual

presentation of PBL required an extensive immunohistochemical

panel as well as correlation of the clinical and radiological

findings. Only with

an understanding of the less common pattern of bone involvement

by PBL as well as excluding carcinoma or other non-hematopoietic

neoplasms due to the marked associated fibrosis was the

diagnosis made. Furthermore,

subtyping of the non-Hodgkin lymphoma is critical to appropriate

management.8,9 This

PBL was of the centroblastic variant, germinal-center like

(BCL-6+, CD10+). In conclusion, a systematic approach to the

pathologic evaluation of bone lesions is of fundamental

importance. PBL has

quite different therapeutic and prognostic significance than the

other more frequently present neoplasms in the differential

diagnosis. Thus, missing the diagnosis of an atypical PBL

presentation can have serious consequences.

Reference :

-

Hicks

DG, Gokan T, O’Keefe RJ et al.

Primary Lymphoma of the Bone.

Cancer 1995;75:973-980.

-

Unni

KK, Hogendoorn PCW. Malignant

Lymphoma, In : Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, eds.

WHO Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics

of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone, Lyon, France: IARC

Press; 2002:306-308.

-

Simon

MA, Bartucci EJ. The

search for the primary tumor of patients with skeletal

metastases of unknown origin.

Cancer 1986;58:1088-1095.

-

Berrettoni

BA, Carter JR. Mechanisms

of cancer metastasis to bone.

J Bone Joint Surg 1986;68:308-312.

-

Mulligan

ME, McRae GA, Murphey MD.

Imaging features of primary lymphoma of bone.

Am J Rad 1999;173:1691-1697.

-

Krishnan

C, George TI, Arber DA. Bone marrow metastases: a survey of

nonhematologic metastases with immunohistochemical study of

metastatic carcinomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol

2007; 15: 1-7.

-

Huebner-Chan

D, Fernandes B, Yang G, Lim M.

An immunophenotypic and molecular study of primary

large B-cell lymphoma of bone.

Modern Pathology 2001; 14: 1000-1007.

-

De

Leval L, Braaten KM, Ancukiewicz M et al.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of bone: An analysis of

differentiation-associated antigens with clinical

correlation. Am

J Surg Pathol 2003: 27:1269-1277.

-

Pettit

CK, Zukerberg LR, Gray MH et al.

Primary lymphoma of bone.

A B-cell neoplasm with a high frequency of

multilobated cells. Am

J Surg Path 1990;14:329-334.

|