|

Abstract:

The

aim of this study was to review a multicentre experience in

treating segmental humeral fractures and report related

complications and outcomes.

From 1996 to 2005 adult patients with segmental humeral

fractures were identified. Demographic details, method of

fixation, time to union and complications were recorded. At

follow up all patients were assessed in terms of radiological

result, range of movement and pain. Pain and range of movement

were combined to give a final outcome rated as good, moderate or

poor.

There were 63 patients.

22 non-operative, 11 intramedullary nailing, 17 plating, 2

Rush pins, 6 Enders nails and 5 external fixation. The non-union

rate was 22.2% (14 patients). 64.2% (9 patients) of the 14

non-union patients went on to union in one, but not both,

fracture sites. The Pearson chi-squared test is highly

significant (p=0.002).

It is clear that some treatments give better results than others

with nails showing better outcomes.

Despite the severity of this injury a satisfactory outcome can

be expected. The most successful method of surgical treatment

was found to be the intramedullary fixation.

J.Orthopaedics 2009;6(2)e6

Keywords:

Segmental;

humeral fracture; multicentre experience.

Introduction:

Segmental

humeral fractures have been successfully treated using closed

reduction and splinting followed by functional bracing21.

Sarmiento et al found consistent restoration of shoulder and

elbow movements with this method of treatment and similar

results were confirmed by others3,5. Severely

comminuted or segmental fractures however treated

non-operatively may predispose to an unsatisfactory outcome13.

Bone distraction and loss of fracture reduction could lead to

delayed or non-union of the fracture15. Surgical

stabilisation is advocated in certain circumstances including

failure of acceptable closed reduction13,6,17, open

fracture with nerve injury4, the multiply injured

patient6, pathological fracture14 and the

uncooperative patient6. Different stabilisation

techniques have been described including intramedullary nailing13,15,6,14,19,

open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF)6,4,16,25

or external fixation16. Intramedullary fixation

offers the advantages of biomechanical load-sharing6,

closed insertion technique6, decreased soft-tissue

disruption13,14 and preservation of the

extramedullary blood supply6. However, this method

has been implicated in the development of shoulder and elbow

dysfunction6,17 malrotation14 and radial

nerve palsy15. Chen et al6 stated that

plate osteosynthesis allows early active mobilisation of the

shoulder and elbow but may require extensive soft tissue

exposure and periosteal stripping13,6,14,15,25 thus

disturbing the local biological substrate of the fracture.

External fixation also plays its part particularly, although

certainly not exclusively, in stabilising open fractures16

but pin site infection, non-union and patient compliance may

limit their use16. Currently, the literature with

regard to the management and outcomes of segmental humeral

fractures remains poor.

The

aim of this study therefore was to review a multicentre

experience in treating segmental humeral (AO type 12B or C)

fractures. We wished to investigate the experience of our

institutions in managing these injuries and report related

complications and outcomes.

Materials

and Methods:

A

retrospective study of all adult patients treated with humeral

fractures in three trauma centres between 1996 and 2005 was

performed using clinical data and radiographs. Inclusion

criteria for participation in the study were the presence of

either a closed or an open fracture of the humerus with a

segmental component. Patients with impending or pathological

fractures were excluded. A segmental fracture was defined as a

two-level humeral fracture with at least one intermediate free

segment.

Fractures

were classified according to the AO system and type 12B or C

were included in the study20. Demographics, injury

severity score (ISS)2, mechanism of injury, whether

the fracture was closed or open (Gustilo Classification12),

presence of associated injuries and method of stabilisation were

recorded. Post-operative data such as the time to union,

incidence of delayed union and non-union, other complications

and range of movement were also recorded. Clinical healing was

defined as pain-free functional range of movement and

radiological union was defined as the evidence of callus

formation in both the antero-posterior and lateral radiographs.

Non-union was defined as a fracture not conforming to these

characteristics by 6 months post-injury. At the final follow-up

the patients were asked to complete a visual analogue scale for

pain (table 1) and examined for range of movement of the upper

limb (table 2). These were combined to give an overall

outcome score of good, moderate or poor (table 3).

|

Pain level on visual analogue scale (1-10)

|

Grade

|

|

1-3

|

Good

|

|

4-6

|

Moderate

|

|

>7

|

Poor

|

Table

1: Grading system for pain

|

Range

of movement

|

Grade

|

|

100%

to 50% of the normal range

|

Good

|

|

Between

50% and 25% of the normal range

|

Moderate

|

|

Less

than 25% of the normal range

|

Poor

|

Table

2: Grading system for range of movement.

|

Combination

of pain grade and range of movement grade

|

Outcome,

for the purposes of results and statistical analysis

|

|

Good

and good

|

Good

|

|

Good

and moderate

|

Moderate

|

|

Moderate

and moderate

|

Moderate

|

|

Moderate

and poor

|

Poor

|

|

Poor

and poor

|

Poor

|

|

Good

and poor

|

Moderate

|

Table

3: How the pain and range of movement grades were combined to

give a final outcome.

The

results were analysed using the Kruskal–Wallis test for

one-way non-parametric ANOVA (analysis of variance) using SPSS,

R18 and Stata23 packages.

Results :

Out

of 810 humeral shaft fractures identified from our prospectively

documented databases, 66 were found to fulfil the inclusion

criteria (8.1%). Out of 66 patients identified, there were 3

deaths all unrelated to fracture treatment leaving 63 cases for

the final analysis (Figure 1a,b,c,d). There were 33 females and

30 males with a mean age of 51.1 years (range 18–95) and a

mean ISS 14.1 (range 9–41). There were 29 type 12B (12B1, 9B2,

8B3) and 34 type 12C (16C1, 5C2, 13C3) fractures. The mean

length of the intermediate segment was 7.9 cm (range

3.5–17.5). The causes of injury included 23 vehicular

accidents, 22 falls from standing (elderly), 13 falls from

heights, 3 skiing injuries, 1 cyclist and 1 climber. Thirty

patients had associated injuries including head, chest, pelvis

and other long bone fractures. The mean follow up was 36 months

(range 24–60).

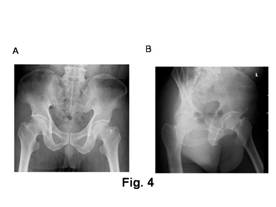

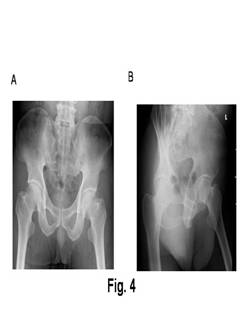

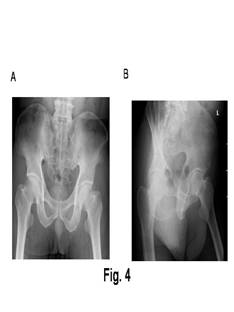

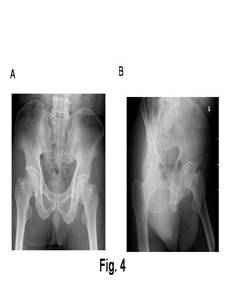

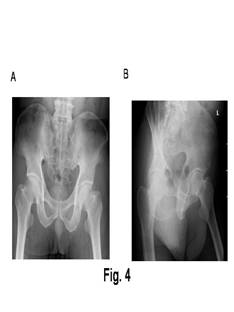

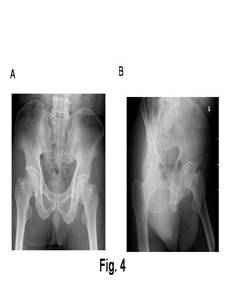

Figure

1a and b

Radiographs showing a segmental humeral fracture in a 55 year

old female following a motorcycle collision.

Figure1

c and d

Antero-posterior and lateral radiographs showing union of the

fractures at the 5 month follow up having been originally

stabilised with plating.

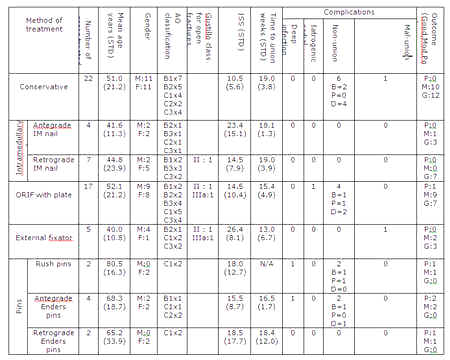

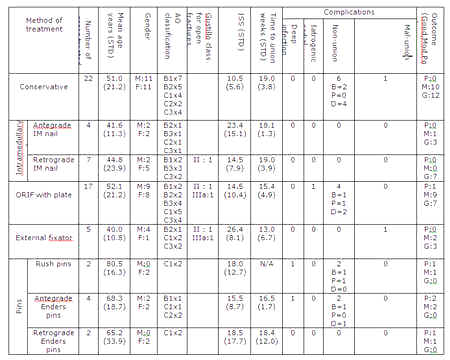

Demographics,

fracture classifications, Injury Severity Scores, methods of

treatment, complications and outcome measures are all presented

in table 4. We correlated total range of movement, complications

and time to union in all patients. For the purposes of analysis,

due to small numbers we combined Enders and rush pins to make

one group of ‘pins’. The overall non-union rate was 22.2%

(14 patients). In 9 out of 14 cases (62.4%) of non-union, one

site united but the other did not. The details are discussed in

the complications section.

Key

Non-union column

B=Non-union both proximally and distally

P=proximal non-union only

D=distal non-union only

Table

4 : Results

Table

5 shows a simple comparison of outcome with treatment group. The

Pearson chi-squared test for association between treatment type

and outcome is highly significant (chi-square = 17.03 with 4

degrees of freedom and p=0.002).

Thus it is clear that some treatments give better results than

others with nails showing more good outcomes and pins much less

so.

|

|

|

Good or moderate/poor

|

Total

|

|

|

|

G

|

MP

|

|

|

Treatment

group

|

cons

|

Count

|

12

|

10

|

22

|

|

|

|

%

within Treatment group

|

54.5%

|

45.5%

|

100.0%

|

|

|

ex

fix

|

Count

|

3

|

2

|

5

|

|

|

|

%

within Treatment group

|

60.0%

|

40.0%

|

100.0%

|

|

|

nail

|

Count

|

10

|

1

|

11

|

|

|

|

%

within Treatment group

|

90.9%

|

9.1%

|

100.0%

|

|

|

pin

|

Count

|

0

|

8

|

8

|

|

|

|

%

within Treatment group

|

.0%

|

100.0%

|

100.0%

|

|

|

plate

|

Count

|

7

|

10

|

17

|

|

|

|

%

within Treatment group

|

41.2%

|

58.8%

|

100.0%

|

|

Total

|

Count

|

32

|

31

|

63

|

|

|

%

within Treatment group

|

50.8%

|

49.2%

|

100.0%

|

Table 5: Treatment group and good or moderate/poor cross

tabulation

The

above analysis is unadjusted for other factors such as sex and

age. Logistic regression was used to adjust for further

factors. A moderate/poor outcome can be predicted for pins and

so these patients were dropped from the analysis. Sex, ISS,

open/closed were all found to be not significant but age and

therapy type remained of interest since they were significant at

the 10% level in this exploratory model. A moderate or

poor outcome is considered bad and the adjusted results are: Age

OR=1.032 per year increase in age (95% CI is (0.999, 1.066), p-0.059)

so that the risk of bad outcome is increased with age; compared

to non-operative treatment, the OR for External Fixation is 5.12

(95% CI (0.43, 6.47), p=0.196),

the OR for Nail is 0.14 (95% CI (0.01, 1.33), p=0.087),

the OR for the Plating group is 1.82 (95% CI (0.47, 6.98), p=0.385).

Figure

2 demonstrates that range of movement varies considerably with

treatment. This is confirmed by Kruskal–Wallis test for

equality of median range of movement which is highly significant

(Chi-square=43.9; df=4, p=0.0001). Nails and external fixation

provided greater range of shoulder movement whilst Enders/Rush

pins and plates were more restrictive than non-operative

treatment.

Figure

2: Total range of movement against method of treatment. A

Kruskal–Wallis test for equality of median range of movement

yields c2= 43.9 with 4 d.f. (p= 0.0001).

Time

to union varies with type of treatment. The variation was small

however, with most fractures healing between 12 and 19 weeks.

The non-operative, plate and Rush/Enders pins groups did have

non-unions as detailed in the complications section of this

paper. Since these patients required revision surgery to achieve

union they did not have a true time union, therefore an analysis

would be unhelpful.

Complications

and outcomes:

a)

Non-operative treatment

Complications are summarised in Table 4. Of the twenty-three

patients who had non-operative management, six progressed to

non-union. Four had united at the proximal but not the distal

site. Two uni-nonunion and two bi-nonunion patients were

operated on with plating, 2 with iliac crest bone grafting.

These patients went on to bony union. The other two uni-nonunion

patients developed painless pseudoarthroses but were left alone

due to acceptable function and co-morbidities. Another

patient’s fracture displaced after a week of conservative

management and required a manipulation in theatre but went on to

union. Another patient developed a malunion but this was left

alone as she was functionally acceptable. There were 2 injury

related radial nerve palsies which both recovered within 4

months fully.

b)

Intramedullary nails

Eleven patients had intramedullary nail fixation. Only one

reported on-going shoulder discomfort post-operatively (antegrade

nail). There were no infections reported and no non-unions. One

case of injury-related radial nerve palsy was noted which

recovered within 8 weeks of the nailing.

c)

Plate fixation

Eighteen patients had plate fixation of their humeral fracture.

Four patients went on to non-union, three of whom had united at

one site but not the other (one ununited proximally and two

distally). Three were revised with further plating and bone

grafting from the iliac crest. The first of these patients had a

broken plate 8 weeks post initial operation. The second patient

was an open fracture which was revised with an LC-DCP at 20

weeks with bone grafting. The third non-union went on to have a

long-stem hemiarthroplasty inserted with a poor eventual

outcome. The fourth patient had a painless non-union and was

left alone. There were 3 radial nerve palsies. Two were injury

related and one iatrogenic intraoperatively. One patient whose

injury caused the palsy, fully recovered and in the other two

only partial recovery was noted.

d)

External fixation

One of the 5 patients in the external fixation group progressed

to a malunion and was taken down and revised with a plate. All

the other four externally fixated fractures (including one open

fracture) went on to satisfactory union. There was one case of

injury-related radial nerve palsy which resolved gradually over

1 month to full recovery.

e)

Pins

Two patients were treated with Rush pins and both progressed to

non-unions. One patient united distally but not proximally and

developed a painless pseudoarthrosis and was left alone. The

other was revised with double recon plates and iliac crest

autograft which then went on to union.

Six

patients had Enders nails inserted, 4 antegrade and 2

retrograde. Four went on to union. There were 2 cases of

non-union (both antegrade) and one of these became infected. The

infected case was later revised with a long stem

hemiarthroplasty with eventual outcome as moderate. The other

case of non-union (united proximally but not distally) had

revision with a plate. One injury related radial nerve

palsy occurred in the antegrade approach group which recovered.

Discussion :

Our

data suggests that patients who have fixation of their segmental

humeral fracture using an intramedullary nail, have a greater

chance of a good outcome than when treated by the other reported

methods.

There

is obscurity in the literature with regards to best treatment

method for the segmental humeral fractures. Balfour et al16

and Sarmiento et al21 stated that when uncomplicated

diaphyseal fractures of the humerus are treated conservatively

by reduction and subsequent immobilisation of the arm,

successful healing occurs in 95% to 98% of cases. However, these

studies are collective retrospective studies for one level, low

energy fractures. In these circumstances non-operative treatment

may be a good option but in our study we are dealing with

segmental fractures which are usually associated with high

energy trauma where significant soft tissue disruption has

occurred. The non-union rate for our non-operative group was

27.2% (6 cases). In many cases one site of the segmental

fracture went on to union but the other site did not. This can

be attributed to compromised biology or biomechanics of

attempted simultaneous healing in two sites.

Closed

locked nailing has been reported to yield satisfactory results

for femoral and tibial segmental fractures13.

Intramedullary nailing has the advantages of being relatively

minimally invasive, offers axial and rotational stability (when

locked) and good alignment. The literature suggests the union

rate for intramedullary nailing of straight forward humeral

shaft fractures is 95% with a low risk of problems such as

mal-union, delayed or non-union, infection or radial nerve palsy9.

In the herein study, locked nailing of segmental humeral

fractures yielded a 100% union rate in a mean time of 18.5

weeks. Amjal1 reported a 30% non-union rate when 33 humeri with

non-segmental but comminuted fractures were nailed using the

antegrade Russell-Taylor nail. He reported no significant

correlation between fracture comminution and healing time. All

the nailings in this study were reamed. One study that compared

nailing with and without reaming was unable to document

differences in union rates or complications9. Recent

interest has been directed towards the issue of axial loading on

surgically stabilised humeral diaphyseal fractures, with

controversy over the ideal method of fixation when it is

necessary6. When compared to plate fixation, for example, it is

generally well accepted that patients can load more confidently

through a nail than a plate4. We had one case of

shoulder pain post-operatively which was associated with one of

the proximally inserted nails. There were no other differences

between the antegrade and the retrograde nail group. We had no

cases of rotator cuff malfunction nor adhesive capsulitis.

Plate

fixation is an alternative method of treating segmental humeral

fractures4,25. The literature reports plating of

non-segmental humeral shaft fractures has a non-union rate of

3.6%14,10 but it traditionally requires an extensive

open operation with a variable degree of stripping of the soft

tissues from the bone. It also provides less secure fixation in

osteoporotic bone or if crutch walking is required14.

An argument for plating against nailing is the accurate fixation

under direct vision and control of malalingment and malrotation.

Plating is a very reasonable method of fixation for fractures

that cannot be nailed, for example, ones that are comminuted

close to the metaphysis (meaning that either the entry point or

the distal locking is compromised) or fractures associated with

radial nerve palsy which require exploration. The results of

plating in this study showed a 23.5% non-union rate. As with the

non-operative group, the relatively high rate of non-union could

be explained by considering that fact that one of the fractures

may not unite as can be the case in segmental fractures in all

long bones. There was also a case of compartment syndrome

post-operatively and one iatrogenic radial nerve palsy.

External

fixation is well recognised as a quick and easy way to stabilise

an extremity fracture whether open or closed. In our study the

results showed a 100% union rate albeit one patient had a

malunion. Care must be taken with pin sites although we had no

cases of deep infection in our study.

Rush

and Enders pins are used less frequently now as compared to

other intramedullary nailing fixation techniques. Here 4 of the

8 patients treated with these methods developed a non-union, 2

due to infection. The reason behind the high rate of non union

is possibly the poor stability that pins and nails provide to

the fracture site and in particular in segmental fractures. The

number of cases also is very small and a type II error could be

present.

We

are aware that this study has a number of limitations including

the retrospective nature, the non-randomisation process, a small

number of cases and the personal experience of four surgeons.

Furthermore the decision to operate or not and the type of

fixation was purely based on the surgeon’s decision. Despite

all of the above, the number of patients treated (63) provides

valid information compared to the current available literature

with scarce numbers of segmental humeral fractures 15,6,17,25.

Strengths of this study include its focus on this specific

subgroup of patients (segmental fractures and not humeral

fracture treatment in general), analysis of the different

methods of fixation (including non-operative treatment), the

multiple outcome measures analysed and the fact that there is an

element of randomisation as supported by the surgeon’s

preference in terms of management decision. The findings

therefore in the herein study can provide valuable information

when such rare cases are considered for stabilisation.

In

conclusion, this study noted consistently good results with

intramedullary nailing. The other management options may also be

considered but a higher rate of complications may be

encountered.

Reference :

-

Ajmal

M, O’Sullivan M, McCabe J, Curtin W. Antegrade locked

intramedullary nailing in humeral shaft fractures. Injury

2001;32:692–4.

-

Baker

S et al. The Injury Severity Score: a method for describing

patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency

care. J

Trauma 1974;14:187-196.

-

Balfour

G, Mooney V, Ashby M. Diaphyseal fractures of the humerus

treated with a ready-made fracture brace. J

Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1982;64-A:11.

-

Bell

M, Beauchamp C, Kellam J, McMurtry R. The results of plating

humeral shaft fractures in patients with multiple injuries. J

Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1985;67-B No.2:293-296.

-

Camden

P, Nade S. Fracture bracing the humerus. Injury

1992;23: 245.

-

Chen

AL, Joseph TN, Wolinsky PR et al. Fixation stability of

comminuted humeral shaft fractures: locked intramedullary

nailing versus plate fixation. J

Trauma, Injury, Infection and Critical Care 2002;

53(4):733-737.

-

Cole

P, Wijdicks. The Operative Treatment of Diaphyseal Humeral

Shaft Fractures. Hand Clinics 2007; 23(4): 437-448.

-

Court-Brown

CM, Garg A, McQueen MM. The translated two-part fracture of

the proximal humerus. J

Bone Joint Surg.2001;83-B(6):799-804.

-

Crates

J, Whittle AP. Antegrade interlocking nailing of acute

humeral shaft fractures. Clin

Orthop. 1998;(350):40-50.

-

Gregory

PR, Sanders R. Compression Plating versus intramedullary

fixation of humeral shaft fractures. J

Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5:215-223.

-

Gregory

P, Sanders R. Compression plating versus intramedullary

fixation of humeral shaft fractures. J

Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5: 215-223.

-

Gustilo

R, Anderson J. Prevention of infection in the treatment of

one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones:

retrospective and prospective analyses. J

Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1976;58:453-458.

-

Ikpeme

J. Intramedullary interlocking nailing for humeral

fractures: experiences with the Russell-Taylor humeral nail.

Injury

1994;Sep(25):447-455.

-

Ingman

A, Waters D. Locked intramedullary nailing of humeral shaft

fractures: implant design, surgical technique and clinical

results. J

Bone Joint Surg [Br]1994; 76-B:23-9.

-

Lin

J, Hou S. Locked nailing of severely comminuted or segmental

humeral fractures. Clin

Orthop and Rel Res 2002;406,195-204.

-

McCormack

R, Brien D, Buckley R et al. Fixation of fractures of the

shaft of the humerus by dynamic compression plate or

intramedullary nail: a prospective, randomised trail.

J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2000; 82,Iss 3; 336-340.

-

Modabber

M, Jupiter J. Operative management of diaphyseal fractures

of the humerus: plate versus nail. Clin.

Orthop 1998;347:93-104.

-

R

Development Core Team (2006). R: A language and environment

for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical

Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0.

-

Remiger

A, Miclau T, Lindsey R, Blatter G. Segmental avascularity of

the humeral diaphysis after reamed intramedullary nailing. Journal

of Orthop Trauma 1997;Vol 11(4):308-314.

-

Ruedi

T, Murphy W et al. (2000). Principles of Fracture

Management. Davos: AO Publishing & Stuttgart New York:

Georg Thieme Verlag.

-

Sarmiento

A, Kinman P, Galvin E et al. Functional bracing of the

humerus. J

Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1977;59-A:596.

-

Stannard

J, Harris, McGwin G, Volgas D, Alonso J. Intramedullary

nailing of humeral shaft fractures with a locking flexible

nail. J

Bone Joint Surg. 2003; 85: 2103-2110.

-

Stata

9.2. Copyright 1984-2006. Statistics/Data Analysis Stata

Corp, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas 77845. USA

(800-STATA-PC) http://www.stata.com 979-696-4600, stata@stata.com.

-

Webb

J. Distal humeral factures in adults. J

Am Acad Orthop Surg.1996;4:336-344.

-

Yang

K. Helical plate fixation for treatment of comminuted

fractures of the proximal and middle one-third of the

humerus. Injury

2005;36:75-80.

|