|

Abstract:

Objective:

This study investigated the characteristics of spontaneous

osteonecrosis of the knee (SONK) in order to establish

appropriate surgical indications.

Materials and Methods:This is a retrospective study of 70

knees with SONK observed in our hospital, with an average

follow-up of 37.9 months after conservative treatment.

Results: The pain and functional scores of the subjects with

SONK significantly improved over the period. X-ray findings

worsened slightly, whereas limb alignment, size of necrosis, and

knee range-of-motion were stable. Of the cases that progressed

to higher X-rays stage during the follow-up period, 71.4% of

knees changed within 12 months of disease onset. Of the cases

that demonstrated stage III to IV at the first visit, 81.1% of

knees maintained the same stage at the final examination.

Conclusions

According to both observations, it seems reasonable to choose

conservative treatment for SONK, even if X-rays of the affected

knee reveal more than stage III severity.

J.Orthopaedics 2009;6(1)e6

Keywords:

knee; osteonecrosis; conservative treatment

Introduction:

Spontaneous

osteonecrosis of the knee (SONK) was first described in 1968

[1]. The

typical SONK patient is a woman over sixty years old who has

sudden onset of severe pain on the medial side of the knee which

often is related to a specific activity or a minor trauma. In

clinical situations, it is sometimes difficult to decide the

timing and indication of surgical treatment because SONK shows

variable prognoses [2-6]. Some cases need surgery because of

severe discomfort and joint deformity, while in others the

symptoms disappear a few months later and no joint deformity

occurs.

We aimed to clarify the characteristics of this disease and

establish an appropriate surgical indication. We hypothesize

that the progression of joint deformity is quite slow or in due

time reaches a plateau if the patient is responsive to

conservative treatment. In this study, we assessed

retrospectively the characteristics of subjects who successfully

continued conservative treatment for SONK.

Materials

and Methods:

We

retrospectively evaluated the natural history of 70 knees in 64

subjects (48 female, 16 male) with SONK, with an average

follow-up of 37.9 months (range 8 to 96). They were selected

from the patient list of our hospital from January 1998 through

December 2007 at their first visit. The average age was 68.9±8.5 years old and the average body mass index was 24.9±3.7

kg/m2. All subjects initially demonstrated positive

magnetic resonance imaging with a well-localized low signal

intensity lesion on T1-weighted images over the medial femoral

condyle that was diagnosed according to past reports [5,7] by

expert radiologists. None of the patients had a history of

cortisone consumption or any disease known to cause secondary

osteonecrosis. The time interval between the onset of symptoms

and the first visit was 13.0 months on average (range 0 to 60

months). All patients were encouraged to exercise the affected

knee at home (description in detail as below) and used a lateral

wedged sole to avoid mechanical overload to the medial

compartment of the knee. Only non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs were used as pain rescue analgesics. The characteristics

of our subjects are summarized in Table 1.

|

Description

|

Total

subjects

|

Acute

group

|

Chronic

group

|

p

|

|

number of knees (subjects)

††

|

70

(64)

|

40

(38)

|

30

(26)

|

.443

|

|

men : women†

|

16

: 48

|

10

: 28

|

7

: 19

|

.815

|

|

age at the first visit ††

(y.o.: minimum to maximum)

|

68.9±8.5

(48

to 83)

|

70.9±6.4

(57

to 80)

|

65.5±10.3

(48

to 83)

|

.123

|

|

body mass index (kg/m2)

††

|

24.9±3.7

|

24.8±3.8

|

24.8±3.2

|

.960

|

|

time interval from the onset to the

first visit (month) ††

|

13.0

(0 to 60)

|

5.7±4.5

|

27.3±12.9

|

.000

|

|

follow-up period (month) ††

|

37.9

(8 to 96)

|

30.1±17.6

|

52.0±18.7

|

.000

|

|

site of necrosis

|

medial

femoral condyle in all cases

|

-

|

† Yates chi-square test

†† unpaired t-test

Table 1: Subject

characteristics

We recommended subjects perform the exercises as follows:

(1) isometric muscle exercises of the bilateral lower limbs, 1

set (each exercise done 20 times) of straight leg rising

training, and hip abduction and adduction exercises twice a day,

in the morning and evening. SLR exercise: Lying on the back,

raise the entire involved leg straight. Be sure to keep the

involved ankle 10 cm above the floor. Hold for 5 seconds, then

slowly lower. Hip abduction exercise: Lying on the uninvolved

side, slowly lift the involved leg straight out to the side to

the horizontal level. Hold for 5 seconds, then slowly lower. Hip

adduction exercise: Sitting on the edge of a table or a high

chair with the knees bent, squeeze an appropriately sized ball

between bended knees. Hold for 5 seconds, then slowly open.

(2) As a ROM exercise, maximum flexion and maximum

extension were performed twice a day in the morning and evening

after the knee was warmed (in a bath or shower). After

decreasing the pain and improvement in symptoms, we recommended

normal speed walking as much as possible to the subjects.

For the clinical and physical evaluation, three scales

that are usually used for osteoarthritis of the knee were used.

With the visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain, patients can

indicate their actual pain level using a 100-mm straight line as

a scale of pain. The JKOM (Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure)

consists of 25 self-completion questionnaires with 4

subcategories: Pain and stiffness during activities of daily

living, social activities, and general health with 100 points as

the maximum score [8],

incorporating the concepts of the World Health

Organization’s International Classification of Functioning,

Disability and Health (ICF 2004) [9]. The (Japan Orthopaedics

Association) JOA score reflects the treatment criteria of the

Japanese Orthopaedic Association, which is used by physicians

for subjective evaluation of sub-categories: pain during

walking, pain when using stairs, range of motion, and swelling,

with 100 points set as the full score [10]. Clinical findings,

as active range of motion (ROM; maximum extension and flexion in

degrees) measured by an orthopaedic goniometer and swelling of

the affected knee in three degrees, non=0, mild=1, moderate or

more=2, were also recorded at the same time.

The radiographic evaluation was also assessed.

Weight-bearing anteroposterior X-rays of the tibiofemoral joint

using the standing extended view (also known as the standing

anteroposterior view) were taken to measure the femorotibial

joint space width (JSW) as the degree of joint deformity [11].

JSW was determined at the center point of the medial

femorotibial compartment on a radiograph using a 0.1-mm

graduated magnifying lens. In order to obtain acceptable X-rays

for accurate reading, we decided to take X-rays according to the

Buckland-Wright criteria [12] in which inter-margin distance (IMD)

of the medial tibial plateau fell within 1 mm. If the IMD was

over 1 mm, another X-ray was taken up to three times. If we

failed to obtain an X-ray within 1 mm of IMD from the three

X-rays, we adopted the X-ray of the least IMD. The femorotibial

angle (FTA) as a parameter of limb alignment was also measured

according to the method of Moreland et al. [13]. In the plane

X-ray examination, we determined X-ray stage according to

Agliatti et al. [2], and also simply assessed the occupied ratio

(OR) of the osteonecrotic lesion in the standing anteroposterior

view because exact measurement of the lesion was sometimes

difficult, especially in the lateral view. In cases of early

SONK with stage I that represented no radiographic abnormality,

magnetic resonance imaging of the affected knee was also used to

measure this ratio instead. All radiographs were obtained by an

experienced expert technician and quantified by a single reader

who was blinded to the features of the subjects.

Statistical

analysis

Seventy knees in 64 SONK subjects were included in the analyses.

Changes in factors including JKOM, VAS, JOA, ROM, JSW, FTA,

X-ray stage, and OR from the first visit to the final status of

follow-up were assessed using a paired t-test for parametric

data, or Wilcoxon’s signed ranks test for other data.

It could not be ignored that our subjects had various time

intervals from the onset to the first visit, and this appeared

to affect their clinical course. Therefore, for analysis we

divided subjects into two groups so as to divide the population

close to equal distribution as follows: One was the acute or

subacute group (n=40) of subjects who visited within 12 months

from the disease onset, and the other was the chronic group

(n=30) of subjects who visited later than 12 months. The

characteristics of all subjects and each group are summarized in

Table 1. The gender difference was estimated by chi-square test,

and other factors were compared using the unpaired t-test. There

was no difference between the both groups except for time

intervals from disease onset and follow-up period.

Linear mixed model analysis was also devised to address the

effect of inter-group and longitudinal course on the eight above

factors. This method

provides the most reliable results as it uses all available data

to estimate the dependent variables. Subjects with at least 8

months’ follow-up were selected for analysis from the

complete, longitudinal dataset. Time intervals from the

first visit through the examination were divided into five

categories as follows; the first visit, less than 12 months from

the first visit, 12 to less than 36 months, 36 to less than 54

months, 54 months or more.

The estimations were made by using 267 observations from 70

subjects. A P value of <.05 was considered significant

and all tests were two sided. All data analyses were conducted

with SPSS for Windows, version 16.0J (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA).

Results:

Pain

and functional scores of the affected knee with JKOM, JOA, and

VAS initially were 34.1, 70.0, and 50.5 on average, respectively

(Table 2). The scores at the final follow-up examination were

22.7, 82.1, and 32.3, and the differences were statistically

significant (P<.01) from the first visit. For radiographic

evaluations, there were also significant differences regarding

JSW and X-ray stage between the first visit and the last

follow-up examination, while OR, FTA and ROM demonstrated no

differences. In the acute group, there were significant

differences between the first and last examinations regarding

JKOM, JOA, VAS, and X-ray stage, whereas no such differences

were seen in the chronic group regarding JOA, VAS, or X-ray

stage.

|

|

Total

subjects (n=70)

|

Acute

group (n=40)

|

Chronic

group (n=30)

|

|

|

first

visit

|

last

observation

|

p

|

first

visit

|

last

observation

|

p

|

first

visit

|

last

observation

|

p

|

|

ROM (degree) ††

|

131.0±16.1

|

132.9±18.7

|

.126

|

131.8±13.0

|

134.8±14.0

|

.189

|

125.3±24.1

|

127.7±27.0

|

.429

|

|

VAS (0-100) †

|

50.5±23.9

|

32.3±27.1

|

.003

|

51.0±20.6

|

33.5±29.3

|

.005

|

41.1±23.2

|

34.5±25.4

|

.325

|

|

JOA (0-100) †

|

70.0±15.5

|

82.1±15.4

|

.000

|

67.8±15.3

|

82.2±16.5

|

.000

|

77.7±14.3

|

81.6±13.6

|

.277

|

|

JKOM (0-100) †

|

34.1±18.3

|

22.7±17.7

|

.000

|

36.4±17.2

|

22.3±18.9

|

.002

|

26.6±14.0

|

18.9±13.0

|

.006

|

|

X-ray stage [2]

(1,2,3,4,5) ††

|

2.9±1.1

|

3.3±.9

|

.000

|

2.6±1.0

|

3.2±.8

|

.000

|

3.2±1.0

|

3.4±.9

|

.102

|

|

occupied ratio (%) ††

|

30.0±15.3

|

32.5±12.8

|

.830

|

29.8±17.1

|

32.7±13.8

|

.433

|

32.0±11.8

|

31.7±12.0

|

.345

|

|

JSW (mm) †

|

2.8±1.2

|

2.6±1.1

|

.014

|

2.8±1.2

|

2.6±1.2

|

.074

|

2.8±1.3

|

2.5±1.0

|

.060

|

|

FTA (degree) ††

|

180.7±4.2

|

181.7±9.8

|

.310

|

180.2±3.8

|

179.0±3.8

|

.276

|

181.5±5.4

|

181.4±4.9

|

.799

|

†

paired t-test

†† Wilcoxon’s signed

rank test

ROM: range of motion, VAS: the visual analogue scale, JOA: the

Japan Orthopaedics Association score, JKOM: the Japanese Knee

Osteoarthritis Measure, JSW: joint space width of the affected

condyle, FTA: the femorotibial angle

Table

2: Differences in variables between the first visit and the

final follow-up

The

changes in the X-ray stage from the first visit through the

final observation are summarized in Table 3, which includes the

cases for whom follow-up periods were at least 12 months. Of 21

cases that progressed to the higher X-ray stage during the

period, 15 knees (71.4%) changed within 12 months of disease

onset. Of 37 cases that demonstrated stage III to IV on the

X-ray at the first visit, 30 knees (81.1%) maintained their

stage level at the final examination.

|

X-ray

stage

|

stage

at the last examination*

|

|

I

|

II

|

III

|

IV

|

V

|

|

stage

at the first visit

|

I

(n=7)

|

1

|

3

|

3

|

|

|

|

II

(n=13)

|

|

5

|

6

|

2

|

|

|

III

(n=24)

|

|

|

18

|

6

|

|

|

IV

(n=13)

|

|

|

|

12

|

1

|

|

V

(n=3)

|

|

|

|

|

3

|

Sixty

subjects with at least 12months’ observation period are

summarized.

* 38.5 months on average (range 12-96).

Table 3:Changes in X-ray staging between the first visit and the

last examination.

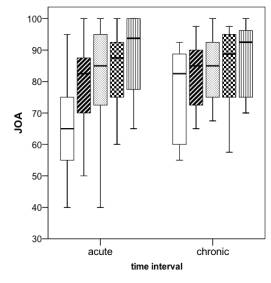

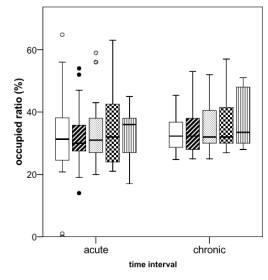

There was no difference in the inter-group analysis regarding

all dependent variables in linear mixed model analysis (Figure

1, Table 4). These

analyses also revealed that VAS, JKOM, JOA, JSW and X-ray stage

changed significantly with time, even in the chronic group. This

means that time intervals are significant to improve of

the functional scores of VAS, JKOM, and JOA. JSW and X-ray stage

worsened slightly, whereas FTA, OR and ROM were unchanged in

each group.

|

Dependent

variables

|

Fixed

effects

|

|

group†

|

time†

|

time*group

|

|

ROM (degree)

|

.128

|

.361

|

.770

|

|

VAS (0-100)

|

.868

|

.015

|

.178

|

|

JOA (0-100)

|

.687

|

.000

|

.053

|

|

JKOM (0-100)

|

.559

|

.000

|

.208

|

|

radiographic stage [2]

(1,2,3,4,5)

|

.195

|

.000

|

.149

|

|

occupied ratio (%)

|

.888

|

.448

|

.618

|

|

JSW (mm)

|

.817

|

.002

|

.233

|

|

FTA (degree)

|

.568

|

.781

|

.490

|

† Univariate

Test.

This test is based

on linearly independent pairwise comparisons among the estimated

marginal means.

ROM: range of motion, VAS: the visual analogue scale, JOA: the

Japan Orthopaedics Association score, JKOM: the Japanese Knee

Osteoarthritis Measure, JSW: joint space width of the affected

condyle, FTA: the femorotibial angle

Table

4 Fixed

effects in the linear mixed model analysis

Typical cases of SONK with conservative treatment are shown in

Figure 2 and 3. A 72 y.o. woman had severe knee pain with acute

onset, scoring 45 on VAS, 54 on JKOM, and 70 on JOA (Figure 2).

She visited our hospital 5 months after the disease onset.

X-rays revealed typical characteristics of stage III SONK and

she was treated conservatively with home exercise and protected

from excess weight bearing. Three

months after the first visit, she complained of

intense knee pain with a VAS score of 90 and requested surgical

treatment. We planned surgical treatment for the affected knee,

but she could not undergo surgical treatment immediately due to

her family reasons. Nine months after the first visit, her pain

decreased gradually, although X-rays showed progression to stage

IV. At the last observation, symptoms had almost resolved and

X-rays showed no progression. She could climb a slope, fold

her legs under herself in the Japanese style ‘seiza’,

and even run a short distance without pain. Scores at the last

examination were 20 on VAS, 11 on JKOM, and 90 on JOA. The OR

was 37.4% and JSW was 2.1 mm at the last observation (-0.8mm

compared to that of the first visit).

Another case of SONK belonged to the chronic group. An 83

y.o. woman who had severe pain with sudden onset 18 months

earlier and was treated at another hospital followed by our

hospital with continued pain, scored 40 on VAS, 30 on JKOM, and

85 on JOA at her first visit (Figure 3). X-rays revealed typical

characteristics of stage III SONK and she was treated

conservatively with home exercise and protected from excess

weight bearing. Twenty-four months after the first visit at the

last observation, symptoms almost resolved and X-rays showed no

progression and slight sclerotic changes. She could climb a

slope and even run a short distance without pain. Scores at the

last examination were 10 on VAS, 9 on JKOM, and 100 on JOA. The

OR was 42.5% and JSW was 4.0 mm at the last observation (no

change from that of the first visit).

A.  |

B.  |

|

Figure 3.

An 83-year-old woman had sudden onset of medial pain in

the right knee. A. Plain radiographs after 18 months

demonstrated a radiolucent area of the medial femoral

condyle that appeared to be stage III SONK, scoring 40 on

VAS, 30 on JKOM, and 85 on JOA. B. After 24 months:

Symptoms had almost resolved and X-rays showed no

progression and slight sclerotic change. Scores at the

last examination were 10 on VAS, 9 on JKOM, and 100 on JOA.

The OR was 42.5% and JSW was 4.0 mm at the last

observation. |

Discussion:

Since

Ahlbach’s first description of SONK in 1968 [1], there have

been many published data concerning its clinical prognosis and

it is well known that the clinical course of this disease varies

from remission with conservative treatment to severe dysfunction

requiring surgical treatment [14].

In the cases of early SONK of stage I that shows no radiographic

abnormalities, there are several reports of a benign prognosis

with conservative treatment [7,15,16]. Yates et al. [16]

described 20 sequential

cases of early SONK diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

in which non-operative management led to the spontaneous

resolution of symptoms and MRI changes at an average of

4.8 months after disease onset.

In our study, most of the stage I cases changed to a

higher stage at the last examination. It is possible that we

missed early stage SONK by omitting of magnetic resonance image

or radioisotope examination in our outpatient department. There

were some attempts to predict the prognosis of SONK in past

reports [7, 17]. It is worth noting that Locouvet et al. [7]

demonstrated that predictive data for irreversible osteonecrosis

by means of MR images was a subchondral low signal on T2 of

>4 mm depth or >14 mm long, focal epiphyseal contour

depressions and low signal lines deep in the affected condyle.

Regarding stage II or higher stages when these radiographic

findings are visible on X-rays, the clinical course and

prognosis were reported to depend on the radiographic size of

the lesion [2,18,19,20]. In these reports, several authors noted

that when a more than 50% of the occupied ratio of the lesion,

and more than 5 cm square of the lesion area, the patient had a

poor clinical and radiographic prognosis with rapid development

of osteoarthritis and surgical treatment was recommended. In

this study, we retrospectively evaluated SONK subjects who were

successfully treated without surgical treatment over the past

ten years. There was no discrepancy between the past reports and

our findings that revealed a 32.5% lesion occupied ratio and

181.7 degrees of FTA on average at the final evaluation (37.9

months’ observation period on average). Aglietti et al.,

suggested other factors that worsened prognosis. They were

flexion contracture and extent of local swelling [2], and our

results were also consistent with these findings. In seventy

knees with SONK, non of the knees represented severe contracture,

and only 4 knees had swelling, scoring 1 in three knees and 2 in

one knee at the final observation. Of these knees, the case with

severe swelling (score=2) had worse symptoms and ROM, but not in

terms of X-ray stage, which consistently showed stage 4 (data

not shown in the results).

The difference between the first visit to the last observation

regarding the eight examined factors in the acute group tended

to be much clearer compared with that of the chronic group

(table 2). The two-comparison analyses (paired

t-test and Wilcoxon

signed rank test) revealed that changes in VAS, JOA, ROM and

X-ray stage were significant only in the acute group.

In our conservatively treated subjects with SONK, however,

linear mixed model analyses revealed that pain and function

gradually improved, JSW and X-ray stage barely progressed, and

no malalignment or joint contracture was seen, regardless of the

time interval from disease onset to the first visit. In

addition, it appears that the improvements in pain and

functional scores were rapid within a year from the disease

onset, although the differences were not significant between the

groups. After that period, the symptoms became stable and joint

deformity tended to be unchanged or remained at a plateau in our

selected population.

Among 60 subjects with SONK who were followed up for at least 12

months, the change in the X-ray stage from the first visit

through the final observation reveals that 71.4% of knees

(15/21) progressed to the higher stage within 12 months from

disease onset (Table 3). Also 81.1% (30/37) of knees with stage

III to IV on X-rays at the first visit maintained the same stage

until the final examination. According to both observations, it

seems reasonable to choose conservative treatment for SONK, even

if X-ray of the affected knee reveals greater than stage III

severity.

In clinical situations, the timing of surgical treatment for

SONK remains controversial. For younger SONK patients with

severe malalignment, proximal tibial osteotomy is preferred in

most cases, while for elderly SONK patients with secondary

osteoarthritis, total knee arthroplasty may be the first choice.

Unicompartmental replacement can be considered for patients with

single compartment involvement and no degenerative changes in

the opposite compartment in the femorotibial joint.

In the early stage, Koshino [14] concluded that bone grafting or

drilling into the necrotic lesion are effective in promoting

osteonecrosis healing, and surgery should be performed in the

early stages of the disease (before the onset of degenerative

changes) to obtain maximum clinical and radiographic

improvement. It remains unclear when surgical treatment is

indicated; the timing depends on whether degenerative changes

have progressed to represent varus knee, an earlier stage of

SONK, or severe impediment of activity of daily living

regardless of these stages.

Although it is clear that there are cases who need surgical

intervention and cases without progression of joint deformity.

Therefore, we think it important to consider the natural course

of SONK under conservative treatment to avoid unnecessary

surgery. Our findings suggest that surgical treatment may not be

the first choice even if symptoms are severe at the first visit,

especially within 12 months, or radiographic examination

demonstrates stage III or later X-ray characteristics. Our

recommended home-based exercise is effective for SONK to

maintain good condition.

There are several limitations to this study as follows. First,

surgical treatment cases were excluded from this study and were

not compared with the present subjects, so we could not show the

cumulative survival rate of SONK with conservative treatment.

Second, a 3-year follow-up period on average may not be

enough to evaluate the prognosis of SONK, and some of our

subjects may undergo surgery in the future.

Third, the term ‘12-months’ from the disease onset in this

study was merely a convenient way to divide subjects into 2

groups according to equal deviation. It is necessary to

calculate an accurate ‘safety’ period cut-off value so the

ROC curve or survival rate can be computed together with cases

of surgical intervention. Another study is required to explore

these issues.

Although there are several limitations as described above, this

study reveals relevance of conservative treatment for SONK.

Further study is needed to explore the accurate timing of

surgical treatment.

Conclusion:

The

70 knees receiving conservative treatment for SONK was

retrospectively assessed. Most cases demonstrated that changes

in the functional scores were correlated with the time interval

from the disease onset, while the radiological aspects did not

progress in the 3 year follow-up period. It appears that

conservative treatment in useful to alleviate SONK symptoms, if

it is over 12-months from disease onset, even if X-rays of the

affected knee reveal greater than stage III severity.

Reference :

-

Ahlbäck

S, Bauer GCH, Bohne WH. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the

knee. Arthritis Rheum 1968; 11: 705-33.

-

Aglietti

P, Insall JN, Buzzi R, Deschamps G. Idiopathic osteonecrosis

of the knee. Aetiology, prognosis and treatment. J Bone

Joint Surg Br 1983; 65: 588-97.

-

Lotke

PA, Ecker ML. Current concept review. Osteonecrosis of the

knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988; 70: 470-3.

-

Björkengren

AG, Al-Rowaih A, Anders L, Thorngren K, Pettersson H.

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee: Value of MR imaging

in determining prognosis. AJR 1990; 154: 331-6.

-

Motohashi

M, Morii T, Koshino T. Clinical course and roentgenographic

changes of osteonecrosis in the femoral condyle under

conservative treatment. Clin Orthop Related Res. 1991; 266:

156-161.

-

Levcouvet

FE, van der Breg BC, Maldague BE, Lebon CJ, Jamart J, Saleh

M, et al. Early irreversible osteonecrosis versus transient

lesions of the femoral condyles: prognostic value of

subchondral bone and marrow changes on MR imaging. Am J

Roentgenol 1998; 170: 71–7.

-

Akai

M, Doi T, Fujino K, Iwaya T, Kurosawa H, Nasu T. An Outcome

Measure for Japanese People with Knee Osteoarthritis. J

Rheumatol 2005; 32: 1524-32.

-

World

Health Organization. International classification of

functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health

Organization 2004. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

-

Koshino

T, Saito T, Wada J, Akamatsu Y. New design of TKA;

unicompartmental arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the knee

using the ceramic YMCK model. In: Niwa S, Yoshino S,

Kurosawa M, Shino K, Yamamoto S eds. Reconstruction of the

Knee Joint. Berlin: Springer, 1997: 200–206.

-

Ravaud

P, Auleley GR, Chastang C, Rousselin B, Paolozzi L, Amor B,

et al. Knee joint space width measurement: an experimental

study of the infl uence of radiographic procedure and joint

positioning. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:761–6.

-

Buckland-Wright

JC, Macfarlance DG, Williams SA, Ward RJ. Accuracy and

precision of joint space width measurements in standard and

macroradiographs of osteoarthritic knees. Ann Rheum Dis

1995;54:872-880

-

Moreland

JR, Bassett LW, Hanker GJ. Radiographic analysis of the

axial alignment of the lower extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am

1987; 69: 745-9.

-

Koshino

T. The treatment of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee by

high tibial osteotomy with and without bone-grafting or

drilling of the lesion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1982; 64:

47-58.

-

Lotke

PA, Ecker ML, Alavi A. Painful knees in older patients.

Radionuclide diagnosis of possible osteonecrosis with

spontaneous resolution. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977; 59:

617-21.

-

Yates PJ,

Calder JD, Stranks GJ, Conn KS,

Peppercorn D, Thomas NP.

Early

MRI diagnosis and non-surgical management of spontaneous

osteonecrosis of the knee. Knee 2007; 14: 112–116.

-

Mont

MA, Baumgarten KM, Rifai A, Bluemke DA, Jones LC, Hungerford

DS. Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg

Am 2000; 82–9:1279–90.

-

Muheim

G, Bohne WH. Prognosis in spontaneous osteonecrosis of the

knee: investigation by radionuclide scintimetry and

radiography. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1970; 52: 605-12.

-

Rozing

PM, Insall J, Bohne WH. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the

knee. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1980; 62: 2–7.

-

Lotke

PA, Abend JA, Ecker M L. The treatment of osteonecrosis of

the medial femoral condyle. Clin Orthop 1982; 171: 109-16.

|