|

Abstract:

The

incidence of primary non-hodgkin’s lymphoma or simply known as

primary bone lymphoma (PBL) is so rare that many of its aspects

remain unknown. Till date only a few reports are available

especially from

Asia

.

Primary lymphoma of bone is uncommon, and because of

its unusual presentation patterns in bone, it can be difficult

to diagnose. According to literature, even though it can occur

at any age,

the

peak incidence is in the fifth decade of life and it is more

common in males. But we report a twenty one year old young

female, who was diagnosed to have primary B-cell bone lymphoma

of the lower end of left femur.

J.Orthopaedics 2008;5(1)e22

Introduction:

Primary bone lymphoma is a rare disease, first described by

Oberling in 1928.[1]. But it was first acknowledged as a

clinico-pathologic entity in 1939 when Parker and Jackson [2]

reported the results of 17 cases of primary reticulum cell

carcinoma of bone.

Primary lymphoma of bone, constitutes approximately 2% of

all bone tumors and 5% of all extra-nodal lymphomas.[3,4].

Primary lymphoma of bone occurs predominantly in males, a male

to female ratio of 1.8:1. [5]. It may occur at any age and the

reported average age of onset varies considerably in the

literature

[5] Peak incidence is in the fifth decade, with a median age of

44. The male to female ratio is 1.8:1. The femur is the

most commonly involved site(29%), followed by the pelvis(19%),

humerus(13%), head/neck(11%), and tibia(10%). Usually patients

present with localized pain, with approximately 50% having a

palpable mass at initial evaluation. [2,6,7, 8,9,10,11,12,13].

Primary lymphoma of bone has been described as a malignant

lymphoid infiltrate within bone with or without cortical

invasion or soft tissue extension and without concurrent

involvement of regional lymph nodes or distant viscera.[9,14].

This entity must be differentiated from other small round

cell tumors originating in bone as well as osseous

manifestations of primary extra-skeletal lymphomas.[12]

An accurate diagnosis requires obtaining a specimen

without crush artifact, as this can alter the cellular

morphologic features and make the diagnosis more

challenging.[15,16,17,18]. Also, lymphoma and osteomyelitis can

coexist.[19,20].

Case

Report :

Twenty

one year old young female presented to our institute in 2007

with history of pain and swelling left knee for three months

duration. Initially she had gradually increasing pain aggravated

by activities like walking and running. Two weeks later she

developed swelling on the medial aspect of left knee. There was

no history of fever, chills or night sweats. There was a history

of weight loss during these three months.

On clinical examination, she had a diffuse swelling on the

medial aspect of the lower end of left femur.with mild effusion

in the left knee joint. Swelling was bony hard, tender, arising

from medial condyle of left femur. Skin was free from the

swelling. She had a decreased range of movements in the left

knee. She had no other masses or lymphadenopathy.

General and systemic examination revealed no abnormalities. Haematological examination was within normal limits. Ultrasound

examination of abdomen was normal. Mantuox test was negative.

Plain roentgenogram of lower end of left femur showed a diffuse lytic lesion just above the medial femoral condyle.(figure-1).

Magnetic resonance imaging of left femur with knee showed

abnormal signal changes with areas of left femur, predominantly

involving the medial condyle.(figure-2). 99Tc MDP whole

body bone scan showed expansile non uniform intense uptake in

lower end of left femur. Rest of the skeleton showed normal

tracer activity and kidneys were normally visualized.

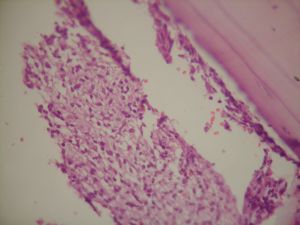

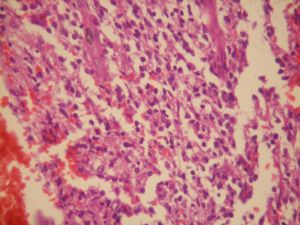

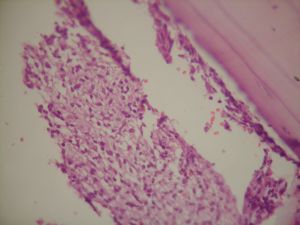

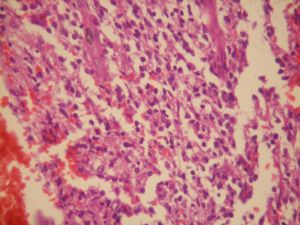

Incisional biopsy was done and the histopathological report

showed immature appearing mononuclear cells with mature

lymphocytes. (figure-3) and (figure-4).

Gross

appearance of the specimen was specimen - grayish , firm

with fragments of bone and soft tissue, and small areas of

haemorrhage with the cortex being thinned out and distended.

Microscopic

appearance was Sections showing bone and soft tissue with

sheets of cells with pale cytoplasm and large nuclei- immature

appearing mononuclear cells with mature lymphocytes.The cells

possessed slightly basophilic cytoplasm with poorly defined

borders, and the nuclei were large, oval to reniform and were

poor in chromatin.

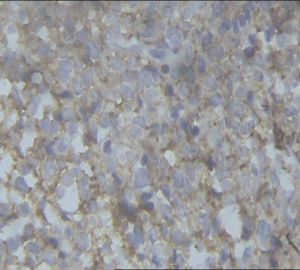

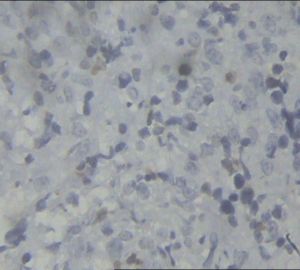

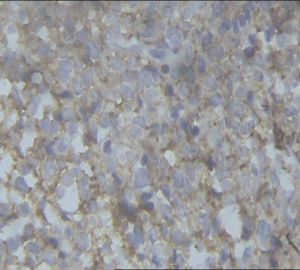

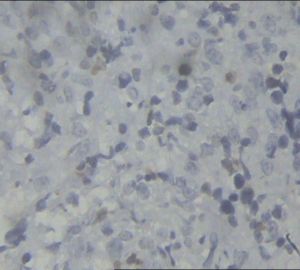

Immunohistochemistry showed CD20: diffusely positive in large

cells. CD3: negative in large cells, thus confirming the

diagnosis of diffuse large B cell lymphoma of lower end of left

femur.(figure-5) and (figure-6). There was sympathetic effusion

in the left knee joint, since the aspirated synovial fluid was

sterile on culture.The patient was treated with CHOP

regime(Cyclophosphamide,Hydroxyl

–Doxorubicin,Oncovin,Prednisolone)i.e: Cyclophosphomide- 600

mg/ m2 ,Hydroxyl-doxorubicin [Adriamycin]- 50 mg/m2 ,Oncovin

[Vincristine]- 1.4 mg/m2 and Prednisolone- 60 mg/m2 .

First

three drugs were given on day 1 and prednisolone is given

from day 1 to day 5. This is repeated every 3 weeks. Six

cycles of chemotherapy (each cycle lasting for three weeks) is

followed by radiotherapy, the dose being 400 cGy units in 20

fractions for a period of 4 weeks.

At

the time writing this report after eight months of first

detection there is no recurrence or evidence of

disease elsewhere in the body as followed up by Technitium 99

MDP Bone scan.

Discussion :

Even though it was first described by Oberling in 1928 [1],

primary bone lymphoma (PBL) was considered as a separate

clinicopathologic entity in 1939 when Parker and Jackson [2]

reported results of 17 cases of primary reticulum cell carcinoma

of bone.

Even after five to six decades of its description, the reports

of PBL are so rare that many aspects remain controversial,

particularly the definition of PBL, appropriate treatment

strategies, response criteria and prognostic factors.[ 5,21].

PBL is notorious for presenting diagnostic difficulties and

mimics other disease processes, especially infection. Tumors

diagnosed and treated as infections are not uncommon. [22] .

Blum et al reported cases of malignant lymphoma, presenting as

infection and treated as such thereby delaying the true

diagnosis and appropriate treatment.[22] . According to a study

by Marshall et al, earlier detection and treatment can effect a

better prognosis.[23] .

Primary lymphoma of bone is uncommon, comprising from 0.2 to 5%

of primary bone tumors.[15,16] . By reviewing the literature, PBL predominantly affects the males, and the femur has been

reported to be the most commonly involved location as a single

site [21] and the peak incidence is in the fifth decade [5] with

median age of forty four. The patient we reported was a

twenty one year old, young female. To the best of our knowledge,

the incidence of primary bone lymphoma in children and young

adults is very rare [5] . The site of involvement was medial

condyle of left femur, with femur being the most common site of

involvement as per the previous case reports in the literature.[

2,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]

According

to the WHO classification [24] , lymphoma involving bone can be

classified into four groups: Group 1, lymphoma with a single

bone site with or without regional lymph-node involvement; Group

2, lymphoma with multiple bones involved, but no visceral or

lymph-node involvement; Group 3, bone tumor with involvement of

other visceral sites or lymph nodes at multiple sites; and Group

4, lymphoma involving any other sites and found by bone biopsy

which was done to rule out possible involvement.

The WHO classification and some previous reports have

indicated that Groups 1 and 2 should be

considered as PBL, but Group 3 should be excluded from

PBL and considered to be systemic lymphoma regardless of the

bone lesion size. An appropriate definition has not been

established by verification, and hence, the subject continues to

be controversial.[21] .

Histopathologically , the previous studies reported

that majority of patients with PBL were Diffuse Large B Cell

Lymphoma (DLBCL) [14,24,25,26,27]. Immunohistochemical staining

showed CD20,CD79a, and bcl-2 positive and CD3,CD5,CD10 and CD23,

cyclin D1 and

terminal deoxynucleotidyl tranferase negative.[21] . In the

patient we reported, the histopathology revealed a diagnosis of Diffuse

Large B Cell lymphoma [DLBCL] (figure-4),(figure-5) and

immunohistochemistry revealed CD3 negative and CD20 positive.

(figure-6) and (figure-7) confirming the diagnosis of DLBCL.

Regarding treatment of primary bone lymphomas, there is

no universally accepted therapeutic approach to the management

of PBL. [28] . Even though the literature recommends combined

modality therapy with both chemotherapy and radiotherapy, a

formal treatment guideline

have not been developed. [5] . Although no formal

treatment guidelines have been established, combined modality

therapy has been shown to yield better prognosis and results

superior to those of radiation therapy alone for primary bone

lymphoma [25,29,30,31,32] . Recent studies have suggested that a

combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy was the best

treatment for patients with primary bone lymphoma.[33,34] .

Hence, our patient was treated with six cycles ( each cycle

lasting for three weeks) of chemotherapy followed by

radiotherapy.

Conclusion:

Primary

lymphoma of bone is rare and uncommon, especially in young

individuals and in females. To the best of our knowledge, the

case we reported is a rare occurrence as per the review of

literature . This condition being rare and could mimic other

diseases especially infection, it should be included in the

differential diagnosis, so that the pathologist will be prepared

in handling biopsied specimen appropriately. If not considered

in the differential diagnosis, the possibility is not raised and

the patient may end up with a wrong diagnosis and inadequate

treatment.

Reference :

-

Oberling

C. Les Reticulosarcomes et les reticuloendotheliosarcomes de la

moelle osseuse (sarcomas d’Ewing). Bull

Assoc Fr Etude Cancer 1928;17:259–96 (in French).

-

Parker

F, Jackson H. primary reticulum cell sarcoma of bone. Surg

Gynecol Obstet 1939;68:45-53.

-

Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ: Occurrence and prognosis of

extranodal lymphomas. Cancer

29:252– 260, 1972.

-

Rudders RA, Ross ME, DeLellis RA: Primary extranodal lymphoma:

Response to treatment and factors influencing prognosis. Cancer

42:406–416, 1978.

-

Valerae O. Lewis, MD, Gregory Primus, MD, Oncologic

Outcomes of Primary Lymphoma of Bone in Adults. Clinical

Orthopaedics And Related Research 415, Pp. 90 – 97.

-

Mendenhall

NP,Jones JJ, Kramer BS, et al. the management of primary

lymphoma of bone. Radiother

Oncol 1987;9:137-45.

-

Parvinen LM, Jereb B, Nisce L. Primary non-hodgkin’s lymphoma(

reticulum cell sarcoma) of bone in adults. ACT

A Radiol Oncol 1983;22:449-54.

-

Bacci

G, Jaffe N, Emiliani E, et al. Therapy for primary

no-hodgkin’s lymphoma of bone and a comparison of results with

Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer

1986;57:1468-72.

-

Boston

HC,

Dahlin

DC

, Ivins JC, Cupps RE. Malignant lymphoma ( so called reticulum

cell sarcoma) of bone.

Cancer 1974;34:1131-7.

-

Dosoretz

DE, Raymond AK, Murphy GF, et al. Primary lymphoma of bone.

Cancer 1982;50:1009-14.

-

Reimer

RR, Chabner BA, Young RC, et al. lymphoma presenting in bone.

Ann intern Med 1977;87(1):50-5.

-

Shoji

H, Miller TR. Primary reticulum cell sarcoma of bone. Cancer

1971;28:1234-44.

-

Wang

CC, Fleischli DJ. Primary reticulum cell sarcoma of bone. Cancer

1968;22:994-8.

-

Pettit CK, Zukerberg LR, Gray MH, et al: Primary lymphoma of

bone. Am

J Surg Pathol 14:329–334, 1990.

-

Lewis SJ, Bell RS, Fernandes BJ, et al: Malignant

lymphoma of bone.

Can J Surg 37:43–49, 1994.

-

Mirra JM: Bone Tumors: Clinical, Radiologic, and Pathologic

Correlation.

Philadelphia

, Lea and Febiger 1989.

-

Ostrowski ML, Unni KK, Banks PM, et al: Malignant lymphoma of

bone. Cancer

58:2646–2655, 1986.

-

Postovsky S, Bialik V, Keidar Z, et al: Large cell lymphoma of

bone presented by limp. J

Pediatr Orthop B 10:81–84, 2001.

-

Eismont FJ, Green BA, Brown MD, et al: Coexistent infection and

tumor of the spine: A report of three cases. J

Bone Joint Surg 69A:452–457, 1987.

-

McGrory JE, Pritchard DJ, Unni KK, et al: Malignant lesions

arising in chronic osteomyelitis. Clin

Orthop 362:181–189, 1999.

-

Dai Maruyama, Takashi Watanabe. Primary Bone Lymphoma: A New and

Detailed Characterization of 28 Patients in a Single-Institution

Study Jpn

J Clin Oncol 2007;37(3)216–223.

-

Y. C. Blum, MD, J. L. Esterhai, MD. Case Report: Lymphoma

Masquerading as Infection .Clinical

Orthopaedics And Related Research , 432, pp. 267–271.

-

Marshall DT, Amdur RJ,

Scarborough

MT

, et al: Stage 1E primary nonHodgkin’s lymphoma of bone. Clin

Orthop 405:216–222, 2002.

-

Fletcher C, Unni K, Mertens F. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours

of Soft Tissue and Bone: World Health Organization

Classification of Tumours.

Lyon

,

France

: International

Agency for Research on Cancer; 2002; 306–8.

-

Heyning FH, Hogendoorn PC, Kramer MH, Hermans J, Kluin-Nelemans

JC, Noordijk EM, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

of bone: a clinicopathological investigation of 60 cases. Leukemia

1999;13:2094–8.

-

Leval L, Braaten KM, Ancukiewicz M, Kiggundu E, Delaney T,

Mankin HJ, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of bone. An

analysis of differentiation-associated antigens with clinical

correlation. Am

J Surg Pathol 2003;27:1269–77.

-

Radaszkiewcz T, Hansmann ML. primary high grade malignant

lymphomas of bone. Virch

Arch[A] 1988;413:269-74.

-

M.Salter, M.D.,R. J.Sollaccio,M.D. primary lymphoma of bone: the

use of MRi in pretreatment evaluation.

Am J Clin Oncol(CCT)12(2):101-105. 1989.

-

Baar

J, Burkes R, Gospodarowicz M: Primary non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma

of bone.

Semin Oncol 26: 270–275, 1999.

-

Dubey P, Ha CS, Besa PC, et al: Localized primary

malignant lymphoma of bone. Int

J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 37:1087–1093, 1997.

-

Fidias P, Spiro I, Sobczak ML, et al: Long-term results of

combined modality therapy in primary bone lymphomas. Int

J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 45: 1213–1218, 1999

-

Loeffler JS,

Tarbell

NJ

, Kozakewich H, et al: Primary lymphoma of bone in children:

Analysis of treatment results with adriamycin, prednisone,

Oncovin (

APO

), and local radiation therapy.

J Clin Oncol 4:496–501, 1986.

-

Barbieri E, Cammelli S, Mauro F, Perini F, Cazzola A, Neri S, et

al. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the bone: treatment and

analysis of prognostic factors for stage I and stage II. Int

J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;59:760–4.

-

Beal K, Allen L, Yahalom J. Primary bone lymphoma:

treatment results and prognostic factors with long-term

follow-up of 82 patients. Cancer

2006;106:2652–6.

|