|

Abstract:

Much

research has been published on aspects of back pain adults,

however, there is comparatively little on the condition in

children. This has occurred despite the fact that back pain is a

common reason for presentation at the pediatric orthopedic

department. In children with back pain an organic cause is more

common than in adults. It is therefore important that orthopedic

surgeons are vigilant to the possible ‘serious’ organic

causes of back pain in children. This case report documents a

common presentation in our emergency department of a child with

back pain who has a non-specific history. The back pain is

subsequently found to be caused by a crush fracture occurring

secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia. A discussion of the

biological causes of back pain in children follows.

Keywords: Spine; Pain; Paediatric; Leukemia

J.Orthopaedics 2007;4(2)e34

Case Report:

An

eight-year girl presented to the emergency department with acute

onset of midline lumbar back pain after minor trauma – a

soccer ball had hit her leg with "force" in the

playground. She had been transferred to hospital by

ambulance as she had been unable to stand initially. She

was reviewed by the orthopaedic registrar on call and a detailed

history revealed that the pain had been present intermittently

for two weeks. There were no specific aggravating movements,

however the pain was exacerbated by general activity and

sneezing. There were no radicular or systemic symptoms.

She gave a vague history of back injury 2 years prior.

On

examination loss of the lumbar lordosis was noted. There

was no tenderness to percussion, but axial compression

exacerbated the mid-lumbar pain. She had a normal straight

leg raise and normal neurological examination.

Plain

radiographs were performed and were thought to demonstrate

subtle loss of height of the L2 vertebral body.

Routine bloods were

normal, and the low back pain resolved in the emergency

department following the administration of oral ibuprofen. A

bone scan was organized with follow-up as an outpatient.

At

a follow-up appointment one week later the patient gave a

history of worsening pain.

Repeat examination revealed tenderness in midlumbar

region, exacerbated by percussion of the lumbar spine.

There were no gross motor, sensory or reflex changes.

Full blood count, electrolytes, erythrocyte sedimentation rate,

and C-reactive protein were once again within normal ranges. The

working diagnosis at this stage was infection or eosinophilic

granuloma.

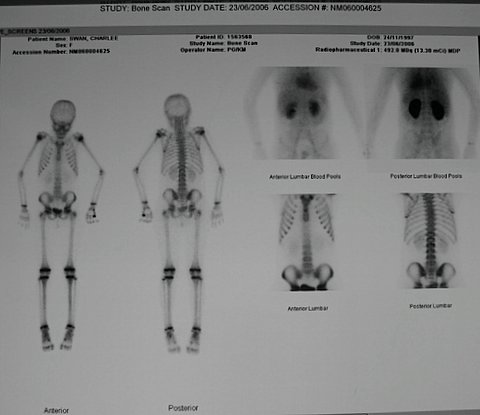

Bone

scan was performed and a subtle abnormality in the superior

aspect of L2 was reported. There was no abnormal blood pool

activity or extension across the disc space. It was concluded

that a diagnosis of discitis was unlikely. Repeat bloods two

weeks after initial presentation were again normal. A renal ultrasound was performed to exclude a renal

cause. An MRI scan

demonstrated an infiltrative process involving several levels at

the lumbar spine. The oncology team was involved and the diagnosis of ALL was

confirmed with bone marrow biopsy.

On retrospective review of initial plain radiographs, it

was agreed that there was osteopenia and pathological fracture

of the superior end plate of L2, consistent with the diagnosis

of an infiltrative process.

Discussion :

The incidence and prevalence of back pain amongst the paediatric

population is not as established as that in adults. A

review of the literature1 found lifetime prevalence rates to

vary between 7-63% in children and adolescents. In the adult

population true bony pathology, aside from degeneration, is

rare. Significantly, in the paediatric population, an acute

organic cause is common2. The differential diagnosis of back

pain in children is included in table 2.

Although occult malignancy is a rare cause of organic back pain

in children, it should form part of the differential diagnosis

of children presenting with musculoskeletal complaints. Atypical

features inconsistent with the provisional orthopaedic diagnosis

should alert the clinician to consider an alternative diagnosis.

Atypical features of a patient’s pain are often known as

‘red flag’ symptoms (see table 3). History taking can be

challenging in trying to establish an adequate pain description

from child. Because of this it is easy to neglect the need to

check for ‘red flag’ symptoms suggestive of serious

pathology. It is essential that children and their parents are

questioned about these symptoms to avoid delays in diagnosis of

a serious condition.

In

a child with red flag symptoms the differential diagnosis would

include.

·

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

·

Septic arthritis

·

Osteomyelitis

·

Discitis

·

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)

·

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

·

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

·

Tuberculosis of the spine

·

Seronegative spondyloarthritis

In

our case the patient’s back pain was caused by ALL. Acute

leukaemia is the most frequent malignant childhood disease with

a peak frequency at two to five years of age. 75% of cases are

lymphocytic in origin (ALL as in our case), 15-20% are

myelogenous leukaemias, and 5-10% are of the non-lymphocytic

type.

Patients

may present with ALL in a variety of ways. Symptoms are usually

related to infiltration of leukaemic cells into the bone marrow

leading to suppression of normal marrow activity. Presenting

symptoms are manifestations of the underlying anemia,

thrombocytopenia, and neutropaenia, and may include fever,

pallor, lethargy, and bruising. Bone pain, particularly

affecting the long bones, is considered to be the result of the

massive proliferation of haemopoietic tissue within the

medullary cavity or periosteum.

In

our case, the only clinical feature was musculoskeletal pain due

to acute pathological fracture.

Bone

pain is not an uncommon initial presentation of leukaemia. In a

study5 of 295 children diagnosed with ALL or malignant lymphoma,

7.1% initially presented to the orthopaedic department with bone

pain. Among these patients 25% specifically had spinal pain. Of

concern Jonsson et al6 reported that patient who listed bone

pain, limp, or other musculoskeletal symptoms as their chief

complaint received a significant delay in diagnosis of acute

leukaemia compared with those that had no musculoskeletal

symptoms.

Routine

blood tests, including inflammatory markers such as ESR and CRP,

are not very useful in categorically excluding malignancy in the

paediatric population. In the study by Kobayashi et al5 it

was noted that the majority of patients with ALL presented with

mostly normal full blood counts. In their laboratory data CRP

was the most sensitive indicator at initial presentation. It was

suggested an elevated CRP without leukocytosis may be an

important finding in patients with leukaemia who complain of

musculoskeletal conditions at initial presentation.

A

significant and encouraging finding in a recent multicenter case

control study by Jones et al7 concluded that in children

presenting with musculoskeletal complaints, the three most

important factors that predicted a diagnosis of ALL were low WCC,

low-normal platelet count, and a history of night-time pain. In

the presence of all 3 of these findings the sensitivity and

specificity for the diagnosis of ALL were 100% and 85%

respectively.

It

is imperative to investigate sites of bony pain and tenderness

with an imaging technique. Gray8 recommends that every child

that presents with back pain that cannot confidently be

classified as innocent should have, at least, standing

anterior-posterior and lateral radiographs of the spine.

Findings on pain x-ray suggestive of malignancy are listed in

Table 4. Kobayashi et al5 found that 94% of patients with

ALL had a radiographic abnormality at presentation, the most

common of which was osteopaenia at the symptomatic area. In

contrast Cabral and Tucker9 found that plain x-ray films

provided diagnostic information in only a quarter of patients.

Importantly, however, they noted that nearly two thirds of

either plain x-rays or bone scans, which were initially reported

as normal before the rheumatology consultation, were then found

to have abnormalities on careful re-examination by a paediatric

radiologist.

In conclusion,

musculoskeletal pain is a common presentation of paediatric

malignancy. As discussed above the results of routine

investigations are often non-specific. Therefore, if there is an

index of clinical suspicion one should have a low threshold for

specialist referral, as MRI scanning, peripheral blood smear and

bone marrow biopsy may need to be undertaken.

Reference :

-

Kovacs F, Gestoso M, del Real M, Lopez J, Mufraggi N, Mendez J .

Risk factors for low back pain in schoolchildren and their

parents: a population based study. Pain. 2003;103:259-268.

-

Weinstein J, Boriani S, Campanacci L. Spine neoplasms. In: Weinstein S (ed). The Pediatric Spine: Principles and

Practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, &

Wilkins;2001:685-707.

-

Sumeet G, Dormans J. Tumours and Tumour-like Conditions of the

Spine in Children. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic

Surgeons. 2005;13:372-381.

-

Waddell G. The back pain revolution. Edinburgh: Churchill

Livingston; 1998

-

Kobayashi D, Satsuma S, Kamegaya M, Haga N, Shimomura S, Fujii

T, Yoshiya S. Musculoskeletal Conditions of Acute Leukemia and Malignant

Lymphoma in Children. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics B.

2005;14:156-161.

-

Jonsson OG, Sartain P, Ducore J, Buchanan G. Bone pain as an

initial symptom of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia:

Association with nearly normal hematologic indexes. Journal of

Pediatrics. 1990;117:233-237.

-

Jones

O, Spencer C, Bowyer S, Dent P, Gottlieb B, Rabinovich C. A

Multicenter Case-Control Study on Predictive Factors

Distinguishing Childhood Leukaemia From Juvenile Rheumatoid

Arthritis. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e840-844.

-

Gray A. Back pain in children and adolescents. Medicine Today.

2005;6:27-33.

-

Cabral D, Tucker L. Malignancies in children who initially

present with rheumatic complaints. Journal of Pediatrics.

1999;134:53-57.

|