|

J.Orthopaedics 2007;4(4)e3

Introduction:

Cooper and Travers first described giant cell tumor of bone in

1818 (4). Bloodgood coined he term giant-cell tumor in 1912(1).

In 1940 Jaffe et al distinguished giant-cell tumor as a

distinct clinical, radiographic, and pathological entity that is

separate from other lesions containing giant cells(8). Giant

cell tumor of bone is characterized radiographically by a well

delineated, eccentric, purely lytic, epiphyseal lesion with the

absence of reactive sclerosis and periosteal new bone formation

abutting the articular surface. Giant cell tumor of the bone

accounts for 4-5% of primary bone tumors and 18.2% of benign

bone tumors. The incidence is increased in patients with Paget

disease of the bone, in which giant cell tumor is a rare

neoplastic complication. Typically, giant cell tumors occur in

skeletally mature patients aged 20-40 years. The incidence peaks

in those aged 20-30 years. Although intraosseous recurrence of

giant cell tumour is a well recognized complication; soft tissue

recurrences are rarely encountered

Case Report:

A

thirty-five year-old man was presented to our institution

because of a gradualy enlarging soft-tissue mass in the

anterolateral aspect of the proximal part of the right leg for

the past six monthsi. Twenty- four months previously, the

patient had been treated by curettage and packing with

polymethylmethacrylate cement for a giant-cell tumor of the

proximal aspect of the right tibia. Physical examination

revealed a nontender soft-tissue mass, seven by four centimeters

in size,mobile,variable in consistancy from bony hard to soft

cystic ; that was palpable in the anterolateral aspect of the

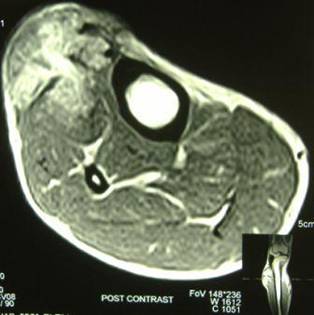

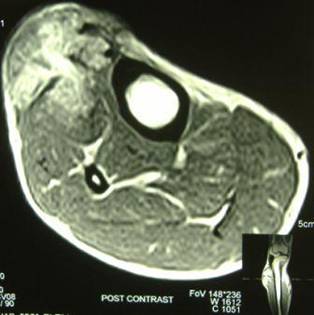

proximal part of the leg. Plain radiographs showed a

soft-tissue mass with more central ossification and

trabeculations (Figure 1-A). The curetted leison with

polymethylmethacrylate cement was intact. Magnetic resonance

imaging studies showed a lobulated well defined hyperintense

mass intending the proximal substance and origin of the

peroneus longus and peroneus brevis with loss of intervening fat

planes-possibly infiltrating the peroneus brevis on T2-weighted

and STIR images.Leison appeared iso to hyperintense to the

muscle on T1-weighted images.Hypointense areas suggestive of

mineralisd septae were seen within the leison.Hyperintense

cystic areas within the leison was also noted(Fig 1B).On

contrast study the leison showed heterogeneous enhancement(Fig

1C).The anterior and posterior intermuscular septum and the

interosseous membrane appeared normal.The patient was managed

with wide resection of the well circumscribed soft-tissue mass,

which measured 7 by 4.2 by 4 centimeters and was located in the

upper peroneal compartment attached to the peroneus brevis

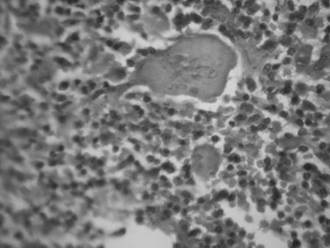

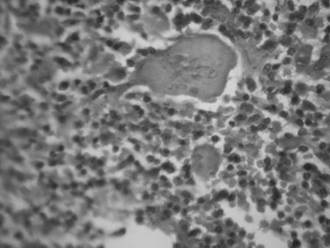

muscle(Fig 1D). Histological analysis demonstrated a recurrent

giant-cell tumor(Fig 1E) .

Fig.1

Fig.2

Fig.3

Fig.4

Fig.5

Discussion :

Intraosseous recurrences of giant cell tumor of bone are

common and readily recognized. O’Donnell et al reported a 25%

rate of local recurrence with thorough curettage and packing

with polymethylmethacrylate (14). Radiologic evaluation of

recurrence typically reveals new areas of bone destruction at

the previous resection margin or resorption of intralesional

bone graft material (9,14,15,16,18,22,23).Recurrence of

giant-cell tumor after polymethylmethacrylate placement

typically reveals focal lobular destruction of bone about the

cement. Soft-tissue recurrences are less common. It is likely

related to either implantation at surgery or tumor spread

secondary to pathologic fracture. Soft-tissue recurrence may or

may not be visible on plain radiographs. Cooper et al. reported

seventeen cases of soft-tissue recurrence in their review of

1100 cases of giant-cell tumor (3). A peripheral rim of

ossification was noted around sixteen of the recurrent

soft-tissue tumors. In the one exception the ossification was

more centrally located within the soft-tissue mass. Other

studies (7, 19,21,) have also reported peripheral rim of

ossification around a soft-tissue recurrence of giant-cell tumor

including pulmonary metastasis, and this phenomenon is thought

to be almost pathognomonic of recurrence. Metaplasia of the

tumor cells may be responsible for this capability of pulmonary

and soft-tissue deposits to produce osteoid (3).The differential

diagnosis to be kept in mind is myositis ossificans. However

these recurrences can be differentiated from myositis ossificans

by their continued slow growth, their occurrence more than 2

months after surgery, and with time, the ossified mass should

increase, rather than decrease in size. The radiographic

appearance of the present reported case with more central

calcification without peripheral rim of ossification matches

that of the lone case reported in the series of Cooper et al.

Most giant cell tumours (80%–90%) recur within

the first 3 years after initial treatment (6, 11, 12, 13, 17,

18, 22).After treatment, patients with GCT should be evaluated

with serial physical examinations and radiography of the

involved site and of the chest. Tumor recurrences have been

noted many years after initial treatment, and necessitate

long-term surveillance (10, 20). A local soft tissue tumor with

a peripheral rim of ossification in a patient with known giant

cell tumor of bone is essentially diagnostic of soft tissue

recurrence of giant cell tumor.

Reference :

with the Study of Bone Transplantation.

Ann. Surg., 56: 210-239, 1912.

2.2Campanacci, M.; Baldini, N.; Boriani,

S.; and Sudanese, A.: Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone and Joint

Surg., 69-A: 106-114, Jan. 1987.

3.Cooper KL, Beabout JW, Dahlin CD. Giant

cell tumor: ossification in soft tissue implants. Radiology1984;

153:597–607.

4.Cooper AS, Travers B: Surgical Essays.

London, England: Cox Longman & Co; 1818: 178-9

5.Dahlin DC: Caldwell Lecture. Giant cell

tumor of bone: highlights of 407 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol

1985 May; 144(5): 955-60

6.Dorfman HD, Czerniak B. Giant-cell

lesions. In:Dorfman HD, Czerniak B, eds. Bone tumors. St Louis,

Mo: Mosby, 1998; 559–606.

7 . Ehara S, Nishida J, Abe M, Kawata Y,

Saitoh H,Kattapuram SV. Ossified soft tissue recurrence ofgiant

cell tumor of bone. Clin Imaging 1992; 16:

168-171

8 Jaffe, H. L.; Lichtenstein, Louis; and

Portis, R. B.: Giant CellTumor of Bone. Its Pathologic

Appearance, Grading, Supposed Variants and Treatment. Arch.

Pathol., 30: 993-1031, 1940

9 194. Kattapuram SV, Phillips WC,

Mankin HJ. Giantcell tumor of bone: radiographic changes

followinglocal excision and allograft replacement.

Radiology1986; 161:493–498.

10 190. Kitano K, Shiraishi T, Iwasaki A,

Kawahara K,Shirakusa T. A lung metastasis from cell tumor ofbone

at eight years after primary resection. JpnJ Thorac Cardiovasc

Surg 1999; 47:617–620.

11. Larsson SE, Lorentzon R, Boquist L.

Giant cell tumorof bone. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1975;

57:167–173.

12. Manaster BJ, Doyle AJ. Giant cell

tumors of bone.Radiol Clin North Am 1993; 31:299–323.

13. Mirra, J. M.: Giant cell tumors. In

Bone Tumors: Clinical, Radiologic, and Pathologic Correlations.

Vol. 2, pp. 941-1020. Philadelphia, Lea and Febiger, 1989

14.O’Donnell RJ, Springfield DS, Motwani

HK, ReadyJE, Gebhardt MC, Mankin HJ. Recurrence of giantcell

tumors of the long bones after curettage andpacking with cement.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:1827–1833.

15. Pettersson H, Rydholm A, Persson B.

Early radiologicdetection of local recurrence after curettageand

acrylic cementation of giant cell tumors. Eur JRadiol 1986; 6:1–

4.

16. Remedios D, Saifuddin A, Pringle J.

Radiologicaland clinical recurrence of giant cell tumour of

boneafter the use of cement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1997;79:26–30.

17 Resnick D, Kyriakos M, Greenway GD.

Tumorsand tumor-like lesions of bone: imaging and pathology of

specific lesions. In: Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders. 3rd

ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders,1995; 3628–3938.

18 Richardson ML, Lough LR, Shuman WP,

Lazerte GD, Conrad EU. MR appearance of skeletal neoplasms

following cryotherapy. Skeletal Radiol 1994;23:121–125.

19 . Serra, J. M.; Muirragui, A.; and

Tadjalli, H.: Extensive distal subcutaneous metastases of a

"benign" giant cell tumor of the radius. Plast. and Reconstr.

Surg., 75: 263-267, 1985.

20 . Scully SP, Mott MP, Temple HT, O’Keefe

RJ,O’Donnell RJ, Mankin HJ. Late recurrence of giantcelltumor of

bone: a report of four cases. J BoneJoint Surg Am 1994;

76:1231–1233.

21 Tubbs, W. S.; Brown, L. R.; Beabout, J.

W.; Rock, M. G.; and Unni, K. K.: Benign giant-cell tumor of

bone with pulmonary metastases: clinical findings and radiologic

appearance of metastases in 13 cases. AJR: Am. J. Roentgenol.,

158: 331-334, 1992

22 . Unni KK. Dahlin’s bone tumors:

general aspectsand data on 11,087 cases. 5th ed. Philadelphia,

Pa:Lippincott-Raven, 1996

23 Waldman BJ, Zerhouni EA, Frassica FJ.

Recurrenceof giant cell tumor of bone: the role of MRI in

diagnosis.Orthopedics 1997; 20:67–69.

|